Hitler's Invasion of Crete – The First Airborne Invasion in Military History

How did the Allies respond? Were they prepared?

In the late spring of 1941 the German juggernaut was still rolling across Europe, and had recently conquered Yugoslavia and Greece—and set its eyes on the more than forty thousand British, Commonwealth and Greek troops that were determined to hold the island of Crete. Under the leadership of General Kurt Student the German's conceived Operation Merkur (Mercury).

It was a daring plan that resulted in a costly victory for the Germans. It saw the first use of Germany's elite Fallschirmjäger en mass but was also the last significant airborne operation conducted by the Nazis in World War II.

The prelude to the battle began in October 1940 when the Italians attacked Greece, which required the government in Athens to deploy the Fifth Cretan Division to stop the invasion from Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's forces on the mainland. The British brokered a deal with the Greeks to garrison the island and use it as a base in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Greek military performed far better against the Italians, who were forced to retreat, and in early April the Germans came to the aid of their Axis partners and invaded Greece. By the end of the month, most of the British and Commonwealth forces had been evacuated to North Africa, while some were sent to Crete but without the heavy equipment, which they left behind.

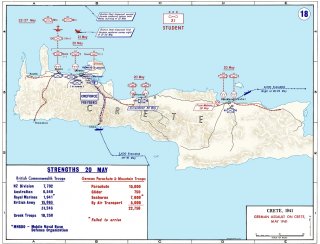

The combined Allied units on Crete were designated “Creforce” under the command of Major-General Bernard Freyberg, who led the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF). Defending the island presented challenges including the fact that the airfields were near the northern coast and faced German-occupied Greece.

The Germans—who were already preparing for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union—both didn't want the British to have a foothold on the island, but also saw that it could be a forward base from which to carry on its own air operations to support the campaign in North Africa.

General Student devised a plan that would employ the Fallschirmjägers in landings to capture the airfields of Maleme, Rethymnon and Heraklion so that their reinforcements could be flown in by the air. It required a total of 500 Junkers Ju-52/3m transport planes—however, those aircraft had been overworked in the recent campaigns and while nearly all were ready the Germans also lacked an appropriate staging area for its airborne armada.

Operation Merkur was launched on May 20.

Creforce had a significant advantage—naming that they were fully aware of the German plans as information was deciphered from German codes. That should have ensured victory for the Allies and a devastating blow to Student's paratroops. However, the British were still unaware of the comparative strength of Germany's sea and airborne forces.

When the German attack began, Freyberg misinterpreted the intelligence and was overly concerned about the seaborne invasion—which in reality was a minor part of the German operation. The British, Commonwealth and Greek forces were deployed to meet the threat from an amphibious assault and that left the largest and most important airfield at Maleme practically open to attack.

Because the Allies knew an attack was coming, even if they didn't know the exact "when," the invaders suffered heavy casualties. German paratroopers landed among Allied defensive positions and most tended to jump with just a sidearm while their main weapons were deployed in separate containers. Even the Germans arriving by glider fared little better and came under immediate fire as they left the aircraft.

The initial assaults against Maleme airfield were repulsed, while subsequent landings near Rethymnon and Heraklion were also pushed back. Even worse for the Germans was that during the first two days of the attack many of the Ju-52s were damaged or shot down. The German high command was even concerned about future airdrops.

However, despite the setbacks and after hard fighting, the Germans were able to turn the tide. This was aided by the use of false radio signals. The Germans gained control of an airfield and were able to fly in additional reinforcements.

Freyberg's forces engaged in a slow, fighting retreat towards the southern coast, and on May 27 he was ordered to evacuate the island. In a show of determination, the 8th Greek Regiment succeeded in holding back a German attack for a week, which allowed Allied forces to move to the port of Sphakia, while the New Zealand 28th (Maori) Battalion also performed heroically in covering the withdrawal.

The bulk of the Allied forces escaped again, but five thousand men protecting the port were forced to surrender on June 1.

It was a hollow victory for the Germans. It cost so many transport aircraft that the Germans never mounted another airborne invasion. Adolf Hitler also believed airborne troops lost the advantage of surprise and he personally directed that paratroopers were only to be employed as ground-based troops from that point on.

The Allies learned valuable lessons and proved Hitler wrong when they used airborne troops effectively during the D-Day operations just three years later.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com.