Laying the Blame for Coronavirus: Why We Should Stop Using the Term 'Patient Zero'

Heightened fears have brought the term into public consciousness.

Both types of stories tend to feature people behaving inappropriately, immorally or wickedly, especially by transgressing important boundaries. These might be natural, religious or geographic divides. One finds examples of proposed “ur-cases” of the pox generated by crossed celestial bodies, crossed species or crossed borders.

These ancient and widespread stories that explain disease and misfortune link to the popular stories of a “patient zero” still told today. They trace real or perceived connections between different people to understand how illness spreads. But unlike the main motivation of public-health contact tracing, a much more recent practice, these stories enact personal distancing through words, aiming to provide reassurance by locating the responsibility for disease elsewhere.

Contact tracing as we now define it developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when investigators and health departments drew upon the remarkable discoveries of bacteriological researchers and applied them to public health problems. Scientists had developed new techniques that allowed them to identify specific germs as the cause of specific diseases. This powerful breakthrough in studying infection, in turn, gave health authorities a much better understanding of how a specific germ was moving through a population and where to allocate resources for prevention.

For diseases such as typhoid fever, tuberculosis, syphilis and gonorrhoea, investigators could now identify potential cases with more confidence. Increasingly, public health workers tested these cases to see if they were carrying specific germs, followed up their contacts, and then applied measures such as treatment, quarantine or isolation to prevent further spread.

The most famous instance of these tools being put to use was with typhoid fever and the case of Mary Mallon in early 20th-century New York. Authorities found this Irish American cook to be a “healthy carrier” – capable of infecting others while remaining symptom-free herself – and they advised her against continuing to work as a cook. When they later traced numerous infections and two deaths to a maternity hospital where Mallon had resumed cooking, she was forcibly confined to North Brother Island for more than two decades until her death in 1938.

In carrying out their responsibilities, public health workers have long benefited from media stories that borrowed heavily from crime fiction, portraying them as tireless “disease detectives”. Alexander Langmuir, the godfather of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the US Centers for Disease Control, actively cultivated such media accounts of his organisation’s epidemiologists from the mid-20th century onward.

One downside, however, to this popular public image is the overlap in word choices and story conventions drawn from crime fiction. Describing public health workers as “disease detectives” opens the door to characterising the contact-tracing process as a “hunt” for guilty “suspects”, people who choose to “give” their infections to innocent “victims” (another harmful story formula with a long history). This is especially troubling if the people in question are going about their lives without the knowledge that they are infected.

It is obvious that a public health method that investigates the same person-to-person connections that have long fascinated members of the public will be particularly vulnerable to mixed messages like these. As a result, writing about contact tracing in relation to a public health emergency must always be done with extreme care. Word choice matters.

Journalists focusing on a “patient zero” risk invoking widespread and historically rooted social impulses to attribute responsibility and blame to the people linked to chains of infection. On their side, public health workers might think twice about using the term “superspreader”. This evocative and stigmatising phrase, still in relatively wide use, describes an infected person who transmits an infection to many others, and has often been applied to the first-ever “patient zero”: Gaétan Dugas.

What we don’t see

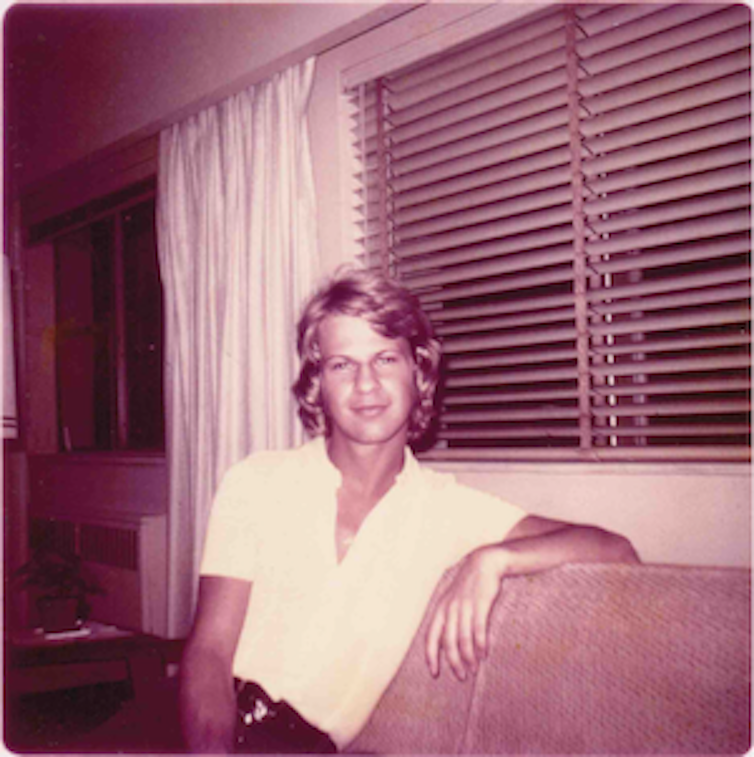

Many people will know the story of Gaétan Dugas, the French-Canadian flight attendant wrongly accused of being “patient zero” of the North American AIDS epidemic. Briefly, this man emerged as a person of interest in 1982 when American public health investigators received reports that a number of gay men with AIDS in California had had sex with one another. This was before a virus was known to be the cause and before a test was available to determine who was sick.

In the absence of a definitive test for AIDS, this sexual network of cases, all of which fit the narrowly defined official case definition for the new syndrome, offered an opportunity to study whether the syndrome was caused by a sexually transmissible agent. The Canadian appeared to provide the sexual link to several Californian cases that otherwise did not have any apparent connection. He was labelled the “out of California” case because he lived outside of the state, and “case O” or “patient O” for short.

The investigators’ detailed contact-tracing work revealed a web of sexual connections, eventually linking cases in California with others in New York and cities in other states. The investigators initially represented this network with “patient O” at the centre. After other researchers later misread the letter O for the numeral 0, many began to misinterpret the person at the centre of the diagram as “patient zero”, the “primary case” for the North American epidemic.

This example has received more attention recently for the personal consequences it had for Dugas’s memory and the pain it brought his loved ones, as well as for the stigmatising story frame that it set up for subsequent “patients zero”. Initially, Randy Shilts’s popularising account, And the Band Played On, even emphasised – using dubious evidence – that Dugas’s refusal to heed public health guidance demonstrated that he was intent on deliberately infecting others.

However, this historical example also offers a useful cautionary tale for thinking about identifiable individuals linked to a cluster of infections, and about asymptomatic cases more generally.

Dugas, the prototypical “patient zero”, did have a very large number of sexual contacts, and some of the connections depicted took place before his symptoms became apparent. But several other men with AIDS represented in the same diagram had as many or more sexual partners. The main difference was that they could not, or would not, share the contact details for their partners in the way that the cooperative Dugas did. The result was that while Dugas’s identified sexual partners radiated out from him in the diagram like spokes on a wheel, these other men were surrounded by empty space.

In this way, the limits of a contact-tracing model focusing on identifiable cases become clear. When we represent something visually, it becomes much easier to focus on what is depicted instead of what might be missing. Similarly, by representing the known connections between people with symptoms, we risk overlooking the just-as-important connections between those who are infectious but symptom free, and who are less likely to be linked to a chain of infection.

There is another way we can now understand the cluster diagram to direct our attention away from what is important. In 1982, it was reasonable to hypothesise that it might only be a few months between someone being exposed to whatever caused AIDS and subsequently displaying signs of the disease. Representing these men’s sexual connections in a diagram made sense because it seemed likely that these depicted exposures were the ones that had permitted a transmissible agent to infect them.

But it became increasingly apparent that it took much longer for people to display symptoms after they were infected, a process which we now understand to be in the order of eight to ten years, in the absence of other health issues. And we now know that by the time that investigations into AIDS began in earnest in 1981, many thousands of Americans were already infected, going about their lives without realising they had acquired a virus that they were transmitting to other people.

So, by the late 1980s, and certainly from our current viewpoint, it is clear that most if not all of the sexual connections depicted in the cluster diagram were not the acts of sexual activity that led to these men becoming HIV-positive. Those exposures would have occurred years earlier, in the early to mid-1970s, beyond the focus of the investigation and therefore left out of the diagram. Not only does this further remove any particular significance attributable to Dugas, but it also importantly reminds us of what we too may be failing to see from our own limited present-day perspective.

In short, by focusing too much of our attention on a “patient zero” or the cases uncovered in a contact-tracing investigation, we risk diverting our attention from the hazards posed by infectious people without symptoms. Also, if we spend too much time thinking about individuals, we risk overlooking steps we can undertake together in our communities.

In other words, the more we can do to think of infection being here among us, instead of over there among them, the more it will allow us to focus on behaviours – things like hand-washing, self-isolation and physical distancing – that can collectively reduce our risk of infection now.