Medicare for All Could Be Cheaper Than You Think

Could it work?

Public support for single-payer health care has been rising in recent months amid failed Republican efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

That’s perhaps why Sen. Bernie Sanders on September 13 introduced a new version of his single-payer plan with the support of 16 Democratic colleagues, a sharp rise from 2013 when none signed on to a similar proposal. It would not only expand Medicare to all Americans but make it more comprehensive by covering more services like mental health, dental care and vision, all without copayments or deductibles.

But Sanders’s plan would come at a steep price: likely more than US$14 trillion over the first decade, based on an estimate I did of a previous version.

There is, however, a simpler and less costly path toward single-payer, and it may have a better chance of success: Simply strike the words “who are age 65 or over” from the 1965 amendments to the Social Security Act that created Medicare and, voila, everyone (who wants) would be covered by the existing Medicare program.

While this wouldn’t be single-payer – in which the government covers all health care costs – and private insurers would continue to operate alongside Medicare, it would be a substantial improvement over the current system.

I have been researching the economics of health care for four decades. While I prefer a more comprehensive universal health care plan that covers all Americans, a simpler version would be much more affordable – and maybe even politically possible.

What Medicare was and what it was meant to be

Striking the words “over 65” from the Medicare statutes was an idea championed by the late Senator Daniel Moynihan. Moynihan, who held several roles in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, was an original architect of the War on Poverty and a central figure in the evolution of health care policy in the latter 20th century.

In fact, many advocates originally intended that Medicare be the basis for universal health insurance. A key reason it serves so well as the foundation is that it includes a funding mechanism – the 2.9 percent Medicare payroll tax paid by you and your employer, alongside modest monthly premiums.

In addition, its limited scope, skimpy benefits and cost-sharing keep costs low. Medicare covers only a little more than half of participants’ health care spending, forcing many elderly Americans to buy private insurance and pay significant out-of-pocket expenses. A little over 11 million poorer participants also rely on Medicaid, especially for long-term care.

For example, Medicare covers hospitalization only after a person has paid the $1,316 deductible, and there’s a copay of $329 per day after 60 days and double that beyond 90. It also covers only 80 percent of the cost of doctor visits and the use of medical equipment – though only after a $183 deductible and the monthly $134 premium.

Still, it provides meaningful protection against the potentially crippling cost of accident or illness.

Giving Medicare to everyone

Single-payer, in its purest form, means the government becomes everyone’s insurer, and private insurance is largely dropped as redundant. This is the way health insurance is provided in the United Kingdom and Canada, as well as other countries like Taiwan. Sanders’s plan would follow this framework.

A simple expansion of Medicare would be more like a hybrid system in which the government program exists alongside private insurers, with residents free to use any combination of the two.

One of the reasons single-payer health care has failed in the United States is that even though it might eventually lower costs, it would require substantial new taxes up front. Sanders’s plan, as I noted earlier, would cost around $1.4 trillion a year. But because of its lower benefit levels and built-in revenue stream, a simple Medicare expansion would cost substantially less, maybe only half that.

In 2015, the last year with complete data, over 55 million Americans received Medicare benefits (including nine million who were disabled). Total spending was $646 billion that year, or an average of $11,000 per recipient.

A simple expansion would add the nondisabled population under age 65 to Medicare: 28 million without insurance, 61 million covered by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Plan and 181 million with private insurance. For the purposes of my calculations, I assume everyone eligible for Medicare would take advantage of the program.

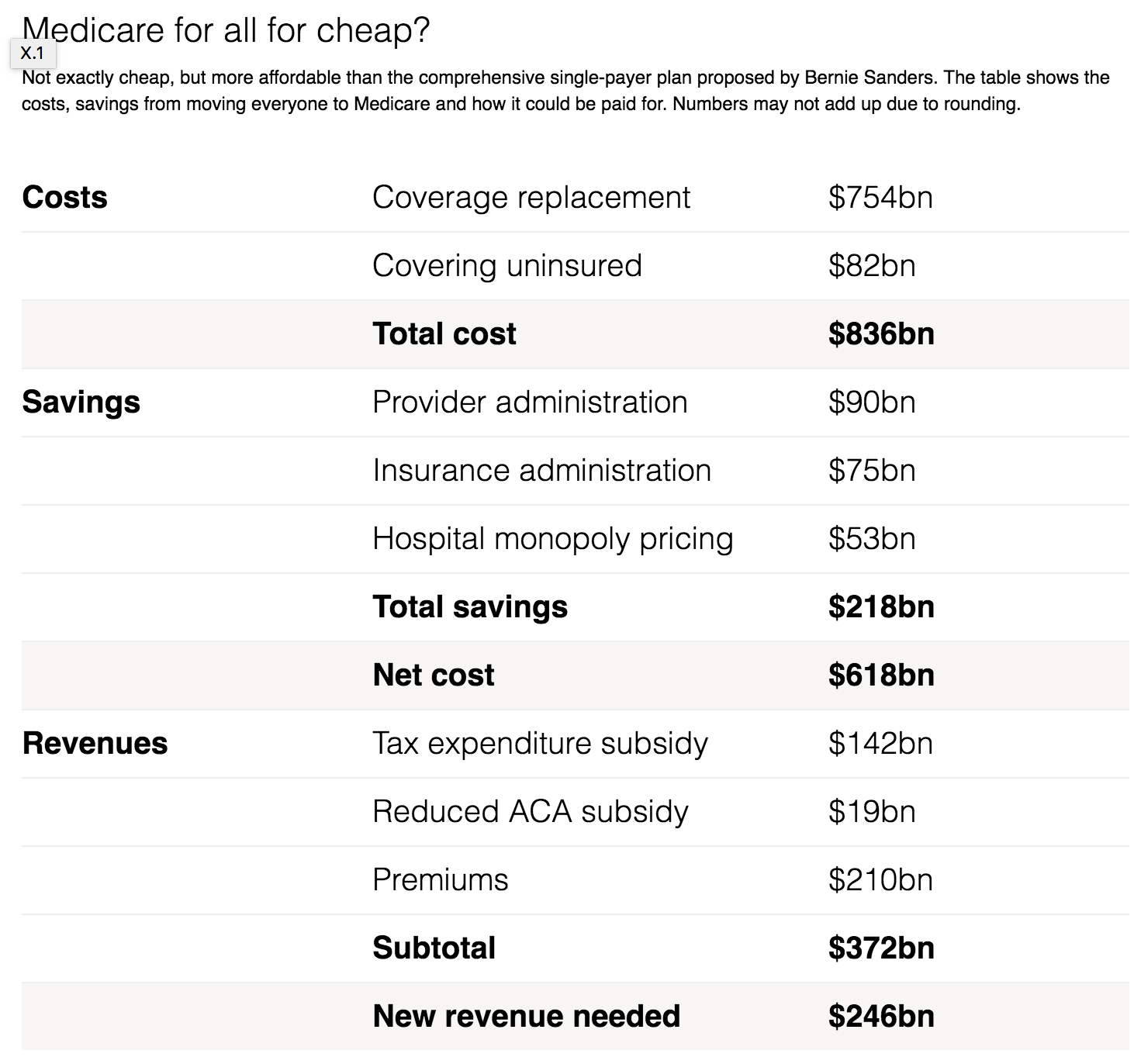

Because the vast majority of the new enrollees would be younger and healthier than current Medicare participants, the cost per person would be much less, or about $5,527 for the once uninsured and $3,593 for everyone else. With a few other calculations, the total price tag of an expansion would tally around $836 billion – almost $600 billion less than Sanders’ single-payer.

Substantial savings

Something that often gets lost in the debate over the cost of single-payer is that its implementation would lead to a host of savings that make the bill to taxpayers a lot less than the sticker price.

I estimate that a full single-payer system would likely save almost 19 percent of current spending, or about $665 billion for 2017. A simple Medicare expansion wouldn’t save quite as much but it’d still be significant.

So where would the savings come from?

To begin with, studies show that medical billing is more expensive in the U.S. than in many countries.

The U.S. health care system spends twice as much as Canada, for example, because more “payers” means more complexity. Savings from a simple Medicare expansion could reduce this waste by about $89 billion a year.

Another source of savings is on insurance administration. Private insurers spend more than 12 percent of total expenditures on overhead, compared with around 2 percent for Medicare. Savings from moving everyone to Medicare would approach around $75 billion because of economies of scale, lower managerial salaries and more meager marketing expense.

A third way a simple Medicare expansion would yield savings is by reducing the ability of hospital monopolies to overcharge private insurers. Medicare, in contrast, is able to pay 22 percent less for the same services because of its size. If all Americans used Medicare savings on hospital costs could exceed $53 billion.

These three areas then would save just under $220 billion, bringing the cost down to $618 billion.

Source: Author calculations

One small step

While $618 billion still seems like a hefty price tag, taxes wouldn’t have to be raised much to pay for it.

For starters, most everyone would pay the premiums already charged by Medicare. This would generate an additional $210 billion in revenue from premiums.

In addition, a Medicare expansion would reduce the need for two current insurance subsidies: one for employer-provided insurance plans and another that the ACA provides insurers. This would save about $161 billion.

This leaves about $246 billion that would still need to be raised through additional taxes. This could be done with an increase in the Medicare tax that gets deducted from your paycheck. The tax, which is split evenly between employee and employer, would need to rise to 5.9 percent from 2.9 percent today. This would amount to just under $15 a week for the typical employee.

Campaigns for universal health insurance coverage have failed in the United States when they run up against the cost of providing coverage. Medicare, America’s greatest success in advancing health care, succeeded precisely because it was limited and had its own dedicated funding streams.

We might learn from this example. Rather than jump all the way to a comprehensive single-payer system like the one Sanders favors, we could take a step along the way at a fraction of the cost by simply expanding Medicare to everyone who wants it.

This article by Gerald Friedman first appeared in 2017 in The Conversation via Creative Commons License.

Image: Reuters