Think Coronavirus Is Bad? The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918 Killed 50 Million People

Including 675,000 Americans.

Coronavirus isn’t the first pandemic to strike the United States. In 1918, just as the United States geared up for the Western Front, a new and virulent disease began to strike US Army training camps. The virus, which eventually took the name “Spanish Flu” in the erroneous belief that the disease came from Spain. Eventually, the Spanish Flu would wreak a terrible toll in the United States and elsewhere.

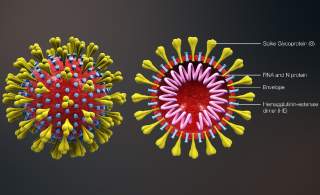

The Virus

In its first years, World War I had promised (or threatened) to overturn the ancient relationship between war and disease, the reality that sickness killed more soldiers than enemy action. This relationship (associated with similar events such as the plague that devastated Athens during the Peloponnesian Wars, and the Plague of Justinian that nearly overwhelmed the Byzantine Empire during its efforts to reconquer Western Europe), resulted from the collection of huge numbers of human beings in close quarters, often with bad food and poor sanitation.

On the one hand, advances in medical technology and sanitation worked to dramatically reduce the toll of disease, especially on the Western Front. On the other, the lethality of automatic weapons and heavy, long-range artillery meant that an increasing proportion of soldiers would die at the hands of the enemy, rather than as a result of viral infections and bacteria.

For the first three years of the war, at least on the Western Front, the modern menace of artillery managed to put the ancient problem of disease in the backseat. This would change with the Spanish Flu, a respiratory disease misidentified as coming from Spain due to the Spanish government’s early identification of the problem. The disease, which most often killed by generating lethal cases of pneumonia, predominantly affected adults between twenty and forty-five, an unusual pattern. This would leave the armies of World War I, including the US Army, deeply vulnerable.

The U.S. Army

As the work of Carol Byerly highlights, the U.S. Army had worked as hard as any to limit the depredations of disease in the early twentieth century. A typhoid epidemic during the Spanish-American War had killed thousands and embarrassed both the Army and the government. As a result, the Army devoted considerable attention to sanitation and to basic medical treatments that would reduce the toll of the disease. The deployment of the Army in tropical areas (such as Panama and the Philippines) had further emphasized the need to find an answer to the spread of disease.

None of this prepared the Army for the Spanish Flu. The first cases of influenza were detected in March 1918 at Army camps in Kansas and Georgia. The first wave of the flu was relatively mild, weakening many soldiers but killing few. As American soldiers began to travel to Europe to fight on the Western Front though, they took the flu with them, often contaminating entire troopships.

The second wave would prove far more devastating. In September 1918, the Allies launched a major concerted offensive that aimed to roll back the successes of the German Ludendorff Offensive, and, indeed, drive the Germans from France. The Meuse-Argonne offensive would be the greatest test of American arms of the war, and American leadership hopes that success would ensure a central position for the United States in post-war peace negotiations. Tragically, the Spanish Flu intervened. During the offensive, the U.S. Army suffered 1,451 fatalities from influenza. By October, the number of sick patients exceeded the number of available beds by some 20,000. The need to transport and care for patients disrupted logistics and transport along the front, contributing even to Erich Ludendorff’s perception that something was sapping the strength out of U.S. offensives.

The U.S. Navy

Sailors, both from the U.S. Navy and from commercial vessels, helped transmit the disease across the port cities of the United States. New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and New Orleans were particularly hard hit. The Navy estimated that over 5000 sailors died of influenza during the war, a toll that affected the ability of the service to man the ships that protected trans-Atlantic supply lines from German submarines. Efforts to maintain quarantines and prevent the transmission of the disease to and from civilian populations were undercut by the military imperative to get as many troops to France as rapidly as possible.

Civilians

The war also made things more difficult for the civilian population. One famous war parade in Philadelphia in October 1918 led to a massive increase in total cases, and consequently to widespread death across the city. 200,000 people attended the parade on September 28, just as the Spanish Flu was reaching its highest degree of lethality. 2,600 died in the first week after the parade, and another 1,900 in the next week. The war had drawn away many doctors and nurses, limiting the availability of quality medical care. Another parade in Boston had similar effects. Moreover, the devastation wrought by influenza did not end with the peace of November 1918. A final wave of the disease struck in 1919, less lethal than the second wave but worse than the first, and wrought an awful toll on returning soldiers and their families.

Conclusion

More than a quarter of the U.S. Army would eventually catch the Spanish Flu, with the Navy suffering a similar proportion of cases. 82 percent of the deaths by disease in the U.S. Army (a slight majority of total morbidity in the Army during the war) were inflicted by influenza. Overall, perhaps fifty million worldwide succumbed to the Spanish Flu, including 675,000 Americans. The war precipitated the pandemic by creating the conditions for its spread, affected the course of the war by weakening armies at critical moments, and reaped the dividends of the war by preying on a weak, hungry populace in the wake of the conflict. Fortunately, the world faces the threat of a modern coronavirus pandemic at a time of relative peace, although ongoing fighting in Syria, and the refugee flow that such fighting might generate, undoubtedly merits serious concerns about the control of the disease.

Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is a Visiting Professor at the United States Army War College. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Image: Reuters