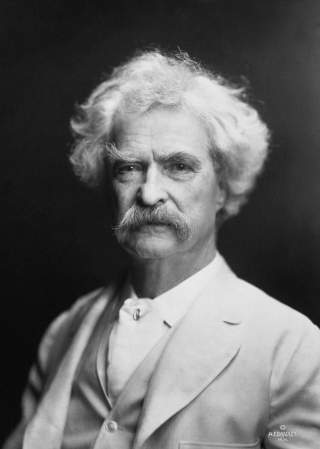

What Would Twain Say? Do Authors Actually Put Symbolism Into What They Write?

Or did your English teacher lie to you?

One of my favorite novels is “Charlotte’s Web,” the famous story of a friendship between a pig and a spider.

I often talk about this novel with my students studying children’s literature. At some point, someone always asks about “deeper meaning.” Is it really a story of, say, the cycle of death and rebirth? Or the importance of friendship? Or the significance of writing?

Or is it just a story of life in the barn, with talking animals?

In a way, it doesn’t matter. Because every writer is also a reader, and that means that whatever a writer puts into a story probably came from somewhere else, whether it’s another story, or a poem, or their own life experience.

And readers, too, will bring their own experience – of other stories, other poems and life – and that will direct their interpretation of what they absorb. We can see one example of this if we look at the spider in “Charlotte’s Web.”

The meaning of character

That spider, Charlotte, is based on a real spider. We know this because E.B. White drew pictures of spiders, studied them and made sure to be as accurate as he could when he wrote about them.

But, to a reader she may also represent Arachne, the talented weaver who challenged the goddess Athena and was changed into a spider for her pride. Or she may be the “noiseless patient spider” of Walt Whitman’s poem, who flings out thread-like filaments as the poet flings out words.

She may also be the spider who weaves “the silken tent” of Robert Frost’s poem. Maybe we’ll think about how the spider, like a human storyteller, generates something seemingly out of nothing, which makes her web miraculous.

Each of these spiders symbolizes different things. When we read about her, then, we may think of all those other spiders. Or we may just think about the spider we saw on our own front porch that morning, weaving her own web.

As the writer Philip Pullman said, “The meaning of a story emerges in the meeting between the words on the page and the thoughts in the reader’s mind.”

The reader is in charge

What Pullman is suggesting, then, is that it’s up to readers to make the meaning they want out of the stories they hear and the books they read.

It’s a powerful statement: We are in charge.

This doesn’t mean that anything goes. Meanings come from context, from convention, from older stories and from previous usage. But it’s up to us to interpret what we read and to make the case for how we’re doing it.

Or, as the novelist John Green writes of his books, “They belong to their readers now, which is a great thing – because the books are more powerful in the hands of my readers than they could ever be in my hands.”

What we do with the books we read matters, Green tells us. It’s up to us to make the meaning and up to us to decide what to do with that meaning once we’ve made it.

Elisabeth Gruner, Associate Professor of English, University of Richmond. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media: Wikipedia