What Your History Teacher Told You About the Maginot Line Is Wrong

The Maginot Line arose neither from French cowardice nor stupidity. It was conceived because of babies—or rather, a lack of babies. France in 1939 had a population of about forty million. Germany had a population of about seventy million. As the Germans themselves learned at the hands of the Soviets, fighting a numerically superior enemy is dangerous.

Or was Paris simply doomed?

“Fixed fortifications are monuments to man’s stupidity,” George Patton said. “If mountain ranges and oceans can be overcome, anything made by man can be overcome.”

No doubt Patton was thinking of the Maginot Line, which has gone down as a salutary lesson in why expensive fortifications are a bad idea.

But with all due respect to Ol’ Blood and Guts (“our blood and his guts,” as Patton’s men used to complain), that’s misreading history.

The Maginot Line arose neither from French cowardice nor stupidity. It was conceived because of babies—or rather, a lack of babies. France in 1939 had a population of about forty million. Germany had a population of about seventy million. As the Germans themselves learned at the hands of the Soviets, fighting a numerically superior enemy is dangerous.

France’s birth rate had actually been declining since the end of the Napoleonic Wars. But World War I worsened the problem. France lost about 1.4 million dead and 4.2 million wounded, while Germany lost two million dead and also 4.2 million wounded. But with almost twice the population, Germany was left with a larger manpower base. As the euphoria of victory in 1918 began to fade, French planners grimly contemplated population graphs predicting the pool of draft-age young men would hit a nadir in the 1930s.

What to do? One solution was to form alliances with the new eastern European states, and even the Soviet Union, to threaten Germany’s eastern border. Another was to count on Britain fighting alongside France to stop a German invasion, as in 1914. Neither would save France in 1940.

That left the traditional solution for a weaker power: the shovel and the concrete mixer. Fortifications are a force multiplier that allow a weaker army to defend against a stronger attacker, or defend part of its territory with minimum forces while concentrating the bulk of its troops for an attack somewhere else.

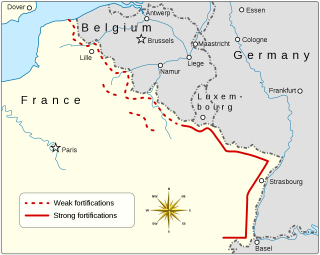

Viewed in this light, the Maginot Line was a sensible idea. It was a line of almost six thousand forts, blockhouses, dragon’s-teeth antitank barriers and other fortifications along the Franco-German border, starting in the south near Switzerland and extending north to the France-Luxembourg border. It was an impressive engineering achievement of retractable cannon-armed turrets that could rise up and down out of the ground, fortified machine-gun nests, and underground quarters complete with cinemas and subterranean trolleys. By all accounts, these were cold, damp places to garrison, yet they would have been quite formidable had the Germans attacked them.

The Maginot Line allowed France to defend its border with Germany with second-rate fortress troops. This let the French concentrate their best armies and their mechanized troops in the open terrain of north of France, where they would advance through Belgium to stop a German attack advancing along the same invasion route taken by the kaiser’s armies in 1914.

This plan might have worked, had the Germans done what they were supposed to. But instead of butting their turrets against the Maginot Line in the south, or the cream of the French army in the north, Hitler’s panzers went up the middle. On May 10, 1940, they struck through Luxembourg and southern Belgium, through narrow country roads traversing forested hills that could have been easily defended by small forces—but weren’t. Six weeks later, France capitulated.

The French campaign of 1940 groans under the weight of what-ifs. What if the Maginot Line had been extended to cover the Belgian border (which would have been an expensive proposition)? What if the narrow roads through Luxembourg had been better defended? What if the French high command had been less lethargic, and moved quickly to seal off the breakthrough? What if French troops had displayed greater initiative and higher morale?

Yet none of these have anything to do with the actual Maginot Line. In hindsight, France could have chosen not to build fortifications, and spent the money on raising more infantry divisions, or buying more tanks and aircraft. But that wouldn’t have solved France’s manpower gap, especially since more troops would have been needed to replace the fortifications along the German border. And there is no reason to believe more money would have resulted in more competent French generals, or that French tanks would have been used more adroitly.

It is a harsh lesson of history that an idea can be brilliant in itself, yet fail for all sorts of reasons. Especially in military history, which is a vast graveyard of plans and technology that didn’t work as advertised. If a jet fighter offers disappointing performance, we consider it a flawed design, and not that jet fighters are a bad concept.

Fortifications are not invulnerable. As Patton observed, any obstacles devised by humans can be penetrated by humans (or by ants, as any home dweller can attest). But used properly, and supported by a field army able and willing to fight, they can be most formidable.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.