Why Israel Is Hoarding Water

Water that Israel promised Jordan back in the 1994 peace treaty has still not materialized. Why?

Two areas farmed by Israelis for more than 50 years have recently been returned to neighbouring Jordan. The first, al Ghamr (known in Israel as Zofar), is located south of the Dead Sea in the Naqab/Negev desert. The second, al Baqura (Naharayim) is found at the fertile point where a major tributary joins the Jordan River.

The association with water bodies is no coincidence: neither land would have been occupied in the first place were it not for the water that the Israeli army and kibbutzim required to sustain the farms.

The return of the lands was made possible by remarkably far-sighted clauses inserted in a 1994 peace treaty between Jordan and Israel. Unfortunately, the parts of the same agreement concerning water could not be more myopic, and ensure that one of the most arid countries in the world – Jordan – remains parched.

Meanwhile, Palestinian farmers do not have enough water. This situation is locked in by a water agreement signed with Israel in 1995, as part of the “Oslo II” process. And as the water levels drop, tensions rise. It gets worse with every scorching summer.

As it controls the most water but needs it the least, Israel has the choice to negotiate fairer agreements. But what must be challenged first is the thinking that led to the agreements in the first place – an economic doctrine which sees water as nothing more than a commodity to be sold or traded, and a political ideology that is fixated on holding on to as much water as possible.

Those who need water most have the least

The effects of the commodification of water are crystal clear at al Baqura. There, the Yarmouk river flows westwards and used to meet the Jordan River mainstream which flows south between Jordan (the country) on one side and Israel and the Palestine West Bank on the other. But these days almost every drop of the Yarmouk not used by farmers in Syria and Jordan is hoovered into a reservoir by farmers in Israel.

The Jordan River itself has run dry ever since 1964, when Israel cornered sole use of Lake Tiberias (aka the Sea of Galilee, or Lake Kinneret) near the river’s source. The Dead Sea at the river’s endpoint has been (apologies) dying, ever since.

Innovators in Israel have in the meantime perfected drip irrigation techniques, implemented impressive schemes which re-use wastewater, and built so many desalination plants that some commentators suggest it now has too much water.

Meanwhile Jordan is increasingly parched, as it hosts millions of people who have fled wars in Kuwait, Iraq, and Syria. With no surface water of its own to speak of, Jordan resorts to desalination on its tiny coastline at Aqaba. It has been encouraged to pump the expensive flows from there to the neighbouring Israeli city of Eilat, in exchange for freshwater Israel is to pump back to Jordan from (the contested) Lake Tiberias.

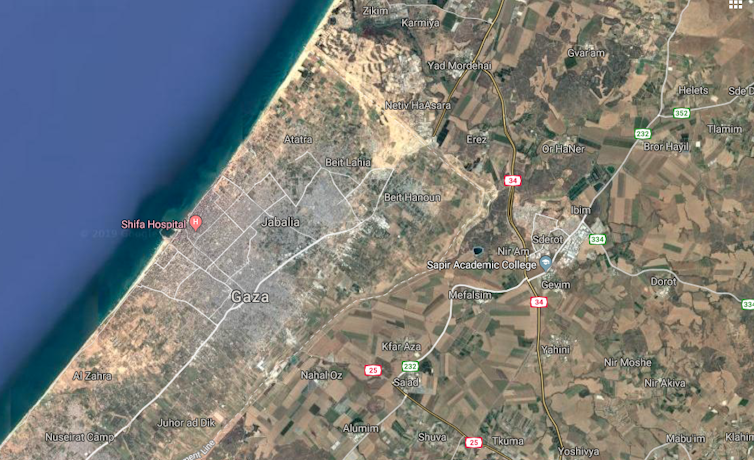

The Palestinian residents of the West Bank actually have less water available now than when Oslo II was signed. In Gaza, desalination is too expensive for most, and with wastewater contaminating the groundwater, “superbugs” are creating a toxic “biosphere of war”. Israel does sell a small amount of freshwater to Gaza, but most of the water it channels from Tiberias 200km to the north stops at the border – tantalisingly in view of the Gazans but out of their reach, reserved instead to grow potatoes that are exported to (a rather wetter) Europe.

Blame ideology, not climate change

There is a tendency to blame climate change or refugees for these policy choices, probably because they cannot talk back. But those who created the mess are the ones who should and can change it.

While the Israeli state doesn’t need so much water, the distribution of control over the Jordan River and associated aquifers remains a mirror reflection of the relative power between the rival states. Israel controls more water than Jordan and the Palestinians combined, and more than double its entitlement when measured against the principles of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention.

Water that Israel promised Jordan back in the 1994 peace treaty has still not materialised. In the West Bank, Israel’s choice to hoard is expressed through the Oslo-created Israeli-Palestinian joint water committee. Because the committee approves the water lines that every new settlement in the West Bank needs, but blocks projects for Palestinian villages, water becomes an effective tool of colonialism or even ethnic cleansing.

Challenge the ideologies, rip-up the agreements

It would be straightforward to invoke guidance from the UN Watercourses Convention, if all that was required to end the Jordan River conflict was updating the agreements. The convention details how water can be shared “equitably and reasonably” and all the states involved signed up – bar Israel.

But first we must challenge the idea that water is a commodity that can be hoarded away or sold only to the highest bidder. But given the extent to which the practice is entrenched in the political and economic systems of the region, evidence and argument are not enough on their own. Researchers can highlight the damage caused by water policy, and environmentalists may question the rationale of exporting desert-grown crops to Europe. Eventually, the task is to replace the blinding ideologies with a strong sense of justice, so that unfair water sharing comes to be seen as unacceptable as slavery.

The required policy and legislation will flow naturally, once this future is seen. It happened at al Baqura and al Ghamr, and it can happen with water.

![]()

Mark Zeitoun, Professor of Water Security, University of East Anglia and Muna Dajani, PhD in Environmental Policy & Development, London School of Economics and Political Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters