Biden Shouldn’t Pressure Seoul into ‘Strategic Clarity’

South Korea's attempts to remain in the good graces of both China and the U.S. are becoming increasingly untenable. Washington runs some serious risks by forcing it to choose.

Amid an intensifying US-China rivalry, South Korea under the Moon Jae-in administration has delicately pursued balanced diplomacy through “strategic ambiguity.” This allows South Korea to benefit from engagement with the United States, its long-standing military ally, and with China, its largest trading partner, without having to choose between them. By maintaining close ties with both Washington and Beijing, yet not band-wagoning with either, Seoul has keenly sidestepped major points of US-China tensions such as issues of military-security, emerging tech, maritime disputes, and human rights. But as relations between the United States and China grow increasingly strained, Seoul faces more expectations from Washington to align with like-minded allies in the Indo-Pacific to counter Chinese influence. Despite the pressure, Seoul will likely stick to strategic ambiguity. One key reason is China’s strategic importance for engaging and denuclearizing North Korea — the Moon administration’s foremost priority.

As North Korea’s sole ally and only real trading partner, China can leverage its influence to coax North Korea into engaging in diplomatic dialogue and nuclear negotiations. In 2017, China’s support was instrumental in pressuring North Korea to pursue a foreign policy shift away from maximal tensions towards active diplomatic engagement the following year. The Moon administration was hopeful the rare momentum for inter-Korean engagement highlighted by 2018’s landmark Panmunjom and Pyongyang agreements would serve as a cornerstone for a long-term Korea peace initiative centered on trust-building via cross-border exchanges. But hope for diplomatic progress vanished at the failed US-North Korea Hanoi summit in 2019 during which Donald Trump urged “full denuclearization before any benefits” and rejected Kim Jong-un’s offer of an interim deal.

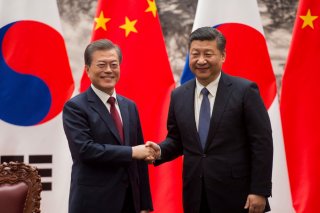

After the Hanoi Summit broke down, Pyongyang engaged in an aggressive show of force, resuming missile provocations, bombing the de facto inter-Korean embassy, and accelerating the development of its nuclear program. But South Korea has remained focused on reviving diplomacy on the Korean peninsula, continually engaging with China to maintain the spirit of joint cooperation around North Korea. Seoul’s ramped-up bilateral engagement with Beijing in recent months, notably the agreement of “ten-point consensus” and multiple high-level meetings involving top Chinese foreign affairs officials Yang Jiechi and Wang Yi, has been primarily driven by one consistent goal — reaffirming Beijing’s “constructive role” in steering North Korea toward diplomacy.

Set to leave the office in just one year, Moon is set on escaping a prolonged deadlock with Pyongyang and taking meaningful steps toward denuclearization and inter-Korean engagement. Anything that might hinder the process, especially prematurely siding with Washington against China (and jeopardizing Seoul’s partnership with Beijing), has been a must-avoid for Moon. But as US-China rivalry continues to intensify, South Korea’s balanced diplomacy is becoming harder to maintain. Pundits in Washington have insisted South Korea should abandon strategic ambiguity for “strategic clarity” by taking a clear, pro-US stance and joining the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) to deepen US-ROK security cooperation.

There are advantages that make joining the Quad an appealing prospect for South Korea, such as escaping a relatively lone position facing China, playing a proactive role in the liberal order, and maximizing trust-building with the United States. But questions remain as to whether such incentives outweigh the potential cost: antagonizing China at the expense of Seoul’s economic relationship with Beijing and losing China’s support on North Korea. History suggests that Seoul has reason to be concerned. South Korea’s 2016 decision to deploy the THAAD, a US missile defense system that Beijing perceives as anti-China military surveillance, was seen as a “stab in the back (背后捅刀子)” as it occurred at the height of friendly relations between the two nations. South Korea’s abrupt commitment to the Quad, which Beijing sees as an anti-China “Asian NATO,” would likely be viewed in the same way and could substantially deteriorate the relationship. Unsurprisingly, Beijing has repeatedly expressed opposition to South Korea’s Quad participation, urging Seoul for “wisdom” in maintaining balanced diplomacy.

The threat of Chinese economic coercion is always nerve-wracking for Seoul, but the more devastating implication would be China’s withdrawal from cooperation on denuclearizing North Korea, which could have a ripple effect throughout the broader region. Beijing has long promoted North Korea’s denuclearization in order to prevent an overly aggressive and nuclear-ambitious Pyongyang from triggering tightened security engagement and extended deterrence of the US alliance architecture in Northeast Asia: the trio of Washington, Seoul, and Tokyo. However, a “Quad-Plus” arrangement that includes South Korea as a member could be perceived by China as an interim US-ROK-Japan trilateral security pact and could galvanize Beijing to reinforce partnerships with Russia and North Korea. From then, denuclearizing North Korea could cease to be a priority for China. On the contrary, Beijing might pivot towards reliance on a nuclear North Korean as a buffer to counterbalance the US-ROK-Japan triangle.

The Biden administration’s new North Korea policy appears to be one of passive engagement that insists on awaiting North Korea’s voluntary return to diplomacy, all the while maintaining pressure and refraining from giving up early concessions. If Pyongyang remains displeased with Washington and continues balking at calls for talks, China’s cooperation will be needed to initiate a pressure-driven dialogue. At the moment, the United States should think twice about pushing Seoul to be more anti-China if Washington intends to benefit from Beijing’s help in engaging Pyongyang. For the US-ROK alliance to try to offset China while simultaneously seeking Chinese assistance would be a fool’s errand.

Demands that South Korea turns toward strategic clarity would be more compelling if Washington was moving away from maximum inflexibility for the sake of maximum engagement with North Korea. The so-far passive and inflexible US approach to diplomacy has only empowered China’s constructive role for engagement and given Seoul more reasons to rely on Beijing. On the other hand, maximum engagement is less China-reliant. When the United States itself becomes a proactive and flexible diplomat that North Korea would find attractive to work with, South Korea can fundamentally worry less about earning Chinese cooperation in convincing and pressuring North Korea towards engagement.

To revive dialogue with Pyongyang, Washington could offer early concessions, including generous aid for COVID-relief, suspension of US-ROK military activities, and an earnest gesture for diplomatic normalization. For example, appointing a special envoy for US-DPRK peace negotiations to replace the existing armistice agreement with a peace treaty and formally end the Korean War. Early concessions by the United States could be perceived by North Korea as a validation of “unhostile US intent” and could induce North Korea’s renewed participation in talks on nuclear disarmament. During negotiations, Washington could seek an interim deal to freeze nuclear operations and provide partial sanctions relief in return. The interim deal could establish the foundational trust for a comprehensive deal — a fully verified, step-by-step dismantlement of nuclear weapons and a nonproliferation agreement in exchange for complete sanctions relief, a peace treaty ending the Korean War, and security guarantees.

Such irreversible progress on denuclearization and peacebuilding in the Korean peninsula would meaningfully reduce South Korea’s dependence on China as Beijing’s role in facilitating dialogue would be largely irrelevant. From there, abandoning strategic ambiguity and taking a clearer pro-US route, though still difficult, could be more manageable for South Korea. After all, replacing strategic ambiguity with strategic clarity should be a shared task in which Washington works with Seoul to create the condition where the consequences are minimized. Pushing for South Korea’s strategic clarity would otherwise have no credibility or appeal.

James Park is the 2021 YPFP Asia-Pacific Fellow. He is a graduate student in International Politics and China Studies at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.

Image: Reuters