China Wants to Bring Peace to the Middle East? Good Luck with That

Before Americans start debating “who lost the Middle East,” as Washington DC did so hysterically after the announcement of the deal, they should probably pause to consider a few plain realities.

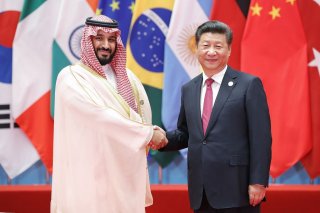

The excitement with which diplomats and pundits reacted to the news about last week’s China-brokered diplomatic deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran, would have led one to conclude that the “handshake heard around the world” wouldn’t only achieve peace between the most powerful Arab-Sunni state, Saudi Arabia, and the Persian-Shiite hegemon, Iran, but would also reshape the regional balance of power if not the entire international system, sidelining the United States and creating the foundations of Pax Sinica in the Middle East.

In a way, it evoked the memories of a historic event: the U.S.-brokered Egyptian-Israeli peace agreement that created the basis for Arab-Israeli peace and, in the process, remade the Middle East, sidelining the Soviet Union from the region and established Washington as hegemon in that part of the world for many years to come.

But that 1979 agreement, facilitated by then-U.S. president Jimmy Carter, was an earth-shattering event. It happened, against the backdrop of the Cold War, following the 1973 Yom Kippur war (which raised the nuclear tensions between the two superpowers) and after the earlier and costly U.S. diplomatic and military interventions in the Middle East that damaged America’s standing in the Arab World and led to a devastating oil embargo.

It was only in the aftermath of that successful 1979 diplomatic triumph that Washington established its dominant role in the Middle East—and it ended up paying higher diplomatic, military, and economic costs for doing so. These include the rise of anti-American terrorism (including 9/11), a series of long and destructive wars in the Middle East, and failed efforts to revive the Arab-Israeli peace process. All of these ended up destabilizing the region, instead of democratizing it, while eroding the U.S. global status, including vis-à-vis rising China.

Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to conclude in the aftermath of the US military interventions in the Middle East that the War on Terror ended—and China won.

While the Americans were fighting and dying in the region, China got busy. It joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 11, 2001, exactly two months after the collapse of the World Trade Center. Facing no serious military challenges, it spent the following two decades strengthening its economy and emerging as a global power ready to compete with the United States. And thanks to the American military interventions in the Middle East, the Chinese benefited from free access to the energy resources in the region. Good deal!

In public discourse, there is now a notion that the Chinese will now replace the United States in a leadership role in the region: mediating between the Saudis and the Iranians, perhaps making peace between the Arabs and Israelis, securing the oil sites in the Persian Gulf, and using its power to stabilize the Middle East, and if necessary, being drawn this war or that war. To some Americans, this may even sound like good news: here are the keys, China; good luck with running this show.

But before Americans start debating “who lost the Middle East,” as Washington DC did so hysterically after the announcement of the deal, they should probably pause to consider a few plain realities. Americans find it difficult to assess the politics of the Middle East and U.S. policy there in binary terms and in a linear fashion: in trying to operate under the assumption that regional alliances are stable and partnerships with outside powers are sustainable, they are always surprised to discover that that isn’t the case.

Hence, in the Middle East, one doesn’t fantasize about remaking the Middle East through wars and regime change, or that a so-called Arab Spring would turn the region into a center of democracy, or that perpetual peace would supposedly flow forth from the Abraham Accords. One can only search for the diplomatic equivalents of one-night stands that may or may not facilitate some long-term changes and more stable relationships.

The United States, not unlike other great powers—including the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France—has discovered that it is impossible for outsiders to impose their agendas on the Middle East. In that region of the world, everything is tied to everything else—the boundaries between local, national, and international issues are blurred. Any attempt by an outside power to impose a solution results in counterforts set up by unsatisfied actors, aimed at forming opposing regional alliances and securing the support of other local players and international actors. As renowned Middle East historian L. Carl Brown suggested, “just as with the tilt of the kaleidoscope, the many tiny pieces of colored glass all move to a new configuration, so any diplomatic initiative in the Middle East sets in motion a realignment of the players.”

One Middle Eastern leader who clearly is familiar with the way things work in the region work is Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), who at one point was imagined by Americans to be a progressive reformer, and then turned into the region’s butcher; a pro-American Arab moderate that would help form a regional NATO to contain Iran, make peace with Israel and help lower energy prices, ends up, to everyone’s shock, partnering with Russia’s evil Vladimir Putin, falling in love with China, and making peace with Iran.

But in fact, it is MBS and not the (Shocked! Shocked! Shocked!) Americans who has correctly read the map of the Middle East and perhaps even what is happening in Washington—and from there operates based on what he considers to be Saudi interests.

MBS, not unlike Israel, rejected U.S. pleas to join the pro-Ukraine camp over the Ukraine War. This is not because he opposes America’s alliance of democracies, but because Russia is Saudi Arabia’s key oil partner. Both states have a common interest to keep oil prices high. It is to Russia with love today, but affairs of that kind don’t last forever—as the Russians who were forced out of Egypt by the late President Anwar Sadat discovered.

MBS, like the Israelis, also recognized that, while America continues to maintain a military presence in the Middle East, it isn’t necessary to go to war against Iran to end its nuclear program or to protect Saudi security, regardless of whether the right-wing Donald Trump occupies the White House or the liberal Joe Biden who replaced him.

The evolving Saudi partnership with Israel—green-lighting the signing of the Abraham Accords and raising the possibility of normalizing relations with the Jewish state—was part of a strategy to counter Iran’s threat. The other side of this plan was a series of negotiations—mediated by Iraq and later by China—to reestablish diplomatic ties with the Islamic Republic. Flirting with Israel doesn’t necessarily mean a full-blown divorce with Iran, and ending the civil war in Yemen is a good thing, even if China is the one that brokers the deal.

That the economic ties between Saudi Arabia and China—the latter of which receives 40 percent of its oil imports from the Middle East—have expanded demonstrates the extent to which “soft power” can play a role in the strengthening of the diplomatic ties between Riyadh and Beijing, despite the fact that China has been accused to persecuting its Muslim minority—a policy that also doesn’t seem to affect Tehran’s ties with Beijing.

But didn’t “soft power” attain a bad name after Germany’s ill-fated attempt to co-opt Russia failed when it came to Ukraine? The Saudis know that when push comes to shove and Iran violates any deal it signs with Riyadh or goes nuclear, China won’t save it from Iran’s military aggression.

Without all the drama surrounding the Iranian-Saudi handshake, it can be seen as another Machiavellian move by MBS to press Biden and his cadre of progressive Democrats to recognize that the Saudis can dance in three weddings at the same time: Riyadh can maintain its partnership with the United States while constructing one with China and trying to play nice with Iran. And that if the Americans would like to see normalization with Israel going forward, they need to provide Riyadh with more weapons and security guarantees. And, no less important, stop bashing MBS.

Dr. Leon Hadar, a contributing editor at The National Interest, has taught international relations at American University and was a research fellow with the Cato Institute. A former UN correspondent for the Jerusalem Post, he currently covers Washington for the Business Times of Singapore and is a columnist/blogger with Israel’s Haaretz.

Image: Shutterstock.