The Afghanistan Exodus: Why America Must Leave Kabul Behind

Today’s world may be too dynamic for Afghanistan to return to its pre-9/11 state. If it is, then America should recognize that other countries will fill the void left after its troops are gone.

If America withdraws from Afghanistan, will it return to the chaos of the 1990s? Those who want the United States to stay fear that it would, with warlords and Islamists vying for control, terrorist groups proliferating and hard-won gains immediately lost. Yet another possible outcome is that regional powers would fill the vacuum and Afghanistan would become their problem instead. The United States can live with this result.

A 2019 Rand Corporation report articulates the view of those who want U.S. soldiers to remain in Afghanistan: following withdrawal, the Kabul government will “lose influence and legitimacy,” power will devolve to regional militias and warlords, and extremist groups will proliferate as the country descends into civil war. The Washington Post’s Max Boot adds that withdrawing would “squander the military’s sacrifices since 2001.” The Council on Foreign Relations argues that the United States has a “vital interest in preserving the many political, economic, and security gains.”

The reality, though, is that the Kabul government is hardly legitimate and its influence comes from buying off regional warlords, often with American aid dollars. Afghanistan, after $2 trillion, twenty-four hundred American lives, and eighteen years of American occupation, is the continent’s poorest country. In Asia, Transparency International says that only Yemen and Syria are more corrupt. Freedom House ranks it as solidly “not free.” In September’s presidential elections, turnout was around 20 percent and just 1.8 million votes were counted—out of a population of thirty-five million. The opposition decried the results, released five months later, as fraudulent.

The Taliban contests or controls 70 percent of Afghanistan, including areas well outside its traditional strongholds. The military stopped reporting Afghan army deaths years ago because they were too high. In 2017, 2.9 percent of the Afghan Army was deserting monthly. Those figures are no longer publicly available either. In 2018, an Afghan general estimated that there were seventy-seven thousand Taliban fighters.

While the war’s backers justify this status quo because they see Afghanistan’s return to the 1990s—and potentially a second 9/11—as the alternative, there is reason to doubt that this would be the actual outcome.

In the 1990s, Afghanistan was a unique product of the times. America had disengaged after the USSR’s withdrawal. Russia was on its knees, descending into lawlessness and facing sovereign default. Thousands of foreign fighters, leftover from jihads in Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Chechnya, had nowhere else to go and Osama Bin Laden—a famous, charismatic leader—to rally around. There weren’t Chinese companies operating there. Terrorism wasn’t taken seriously.

Today, Afghanistan’s neighbors have significant interests there that the United States does not. Pakistan wants a stable and pliant Kabul, as it did before, however it would be less accommodating of the Taliban’s pre-9/11 extremism, given that this support boomeranged back into an insurgency that left over one hundred thousand Pakistanis dead. Pakistan would have to compromise with Iran, which has a stake in protecting Afghanistan’s Shia minority. China and Russia have a mutual interest in stability. China borders Afghanistan and dozens of Uighurs formerly trained alongside Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. Millions of Central Asians work in Russia and Moscow doesn’t want them radicalized.

Afghanistan also has economic appeal to its neighbors that it lacks for the United States. For American companies, Afghanistan is too corrupt, unstable, and violent. Not for state-backed Chinese ones, though, which would have the necessary economic and political backing to mine Afghanistan’s $1 trillion-plus in minerals. Already, the state-owned China Metallurgical Group has a thirty-year lease to develop a copper mine, while the China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) has the right to drill and refine Afghan oil. Afghanistan has vast solar and wind power potential, which Chinese renewable energy companies would seek to cultivate.

Russian, Iranian and Chinese companies would also look to build the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India pipeline, which would bring Turkmen gas to the South Asian market and require long-term political stability. In the 1990s, UNOCAL, an American oil company, spent years trying to facilitate this before abandoning it in the face of domestic pressure and political instability. Regional oil companies would operate as arms of their governments, which would see an opportunity to expand their influence in South and Central Asia. They are more likely to have economic and diplomatic backing to succeed.

Other U.S. concerns—women’s rights, economic development, and opium production—persist or have grown in the last eighteen years. Fourteen thousand troops won’t solve them. U.S. bases in Afghanistan would be desirable too, yet they don’t merit the current commitment. Instead, the United States should continue unilateral strikes on Islamic State and Al Qaeda targets in Afghanistan without endlessly deploying troops there. America should reallocate its resources to emerging threats elsewhere, like in the Sahel, where the United States is considering troop drawdowns despite growing security risks.

Today’s world may be too dynamic for Afghanistan to return to its pre-9/11 state. If it is, then U.S. policy should recognize that other countries will fill the void left after its troops are gone. This wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing, and it’s unlikely to be much worse than Afghanistan’s situation today.

Max Frost is a senior research associate at the American Enterprise Institute.

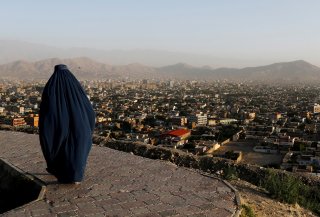

Image: Reuters