Will China Strengthen Iran’s Military Machine in 2020?

Washington needs to work closely with its regional partners to dissuade China from making this choice, or else risk facing a significantly stronger Iran in the coming years.

Following the recent U.S. drone strike on Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, China’s foreign minister told his Iranian counterpart that the two countries should jointly oppose “unilateralism and bullying.” Such rhetorical volleys, while offering a pointed critique of U.S. actions, belie the reality that Beijing has carefully limited its support for Iran’s military modernization for the last fifteen years. As UN Security Council restrictions on arms transfers to Tehran begin to expire later this year, however, a combination of market opportunities, strategic incentives, and weakening political costs could lead Beijing to reconsider its cautious approach. A return to a strong Sino-Iranian arms partnership, which flourished in the 1980s, would embolden Tehran by filling some of its conventional weapons gaps and bring new challenges for U.S. and allied forces. Washington needs to work closely with its regional partners to dissuade China from making this choice, or else risk facing a significantly stronger Iran in the coming years.

China’s Mixed Motives

Since the 1979 revolution, the Chinese strategy towards Iran has fluctuated based on external opportunities and constraints. On one hand, Beijing has long pursued economic interests, especially in terms of exports of consumer products and investments in Iran’s oil and natural gas sectors. Additionally, in the 1980s, China became Iran’s top arms supplier, profiting from the ongoing Iran-Iraq war. China’s key transfers included assets such as tanks, J-7 fighters, armored personnel carriers, surface-to-air missiles, and Silkworm anti-ship cruise missiles valued at $1 billion, several of which were used against foreign tankers and Kuwaiti infrastructure. Iran was also a useful ally in China’s relations with the two superpowers: China’s military assistance helped to build Iran into a “bulwark” against the Soviet Union and was later a card that could be played in talks with the United States on other issues, including U.S. arms sales to Taiwan.

On the other hand, a desire to escape its post-Tiananmen isolation and avoid U.S. sanctions led China to reduce cooperation with Iran in nuclear and ballistic missile technology. Following revelations about Iran’s illicit nuclear program in 2003, China began to curtail its oil imports, arms sales, and diplomatic exchanges. In 2010, Beijing approved wide-ranging UN Security Council sanctions that included restrictions on most conventional arms sales to Iran. These sanctions created restrictions for China (but it continued to tolerate some illicit arms and missile technology trafficking, notably by Li Fangwei). These actions were consistent with China’s avoidance of overt support for “rogue regimes” such as Iran, Sudan, and North Korea, before and after the 2008 Olympics. A final constraint was China’s need to balance its ties between Iran and other regional powers, especially Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich Gulf states, helping to explain China’s reluctance to take sides in regional disputes.

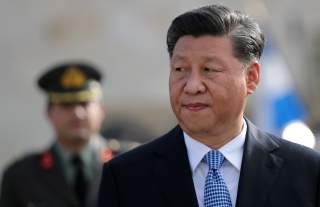

A turning point came with the EU-led negotiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2013–15. This agreement reduced Iran’s pariah status and created opportunities for foreign firms to legally operate there. China took advantage of the agreement by dispatching Xi Jinping in January 2016 to sign a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with Iran, which envisioned greater cooperation in the energy and infrastructure fields. The two sides also agreed to improve military cooperation in training, counter-terrorism, and “equipment and technology.” According to an NDU database, China held twelve military interactions with Iran between 2014 and 2018, including naval port visits, bilateral exercises, and high-level dialogues. Such activities continued last year: in September, the Iranian Armed Forces chief met his counterpart in Beijing and toured a Chinese naval base, and in December, Chinese, Iranian, and Russian naval forces conducted an inaugural drill in the Gulf of Oman.

Despite the resumption of other kinds of diplomatic, economic, and military engagements, China has continued to refrain from selling arms to Iran (except in an indirect way by tolerating the activities of Li and other traffickers). While most conventional arms transfers are permitted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the agreement requires approval from the UN Security Council for five years following the ratification of the agreement (October 8, 2015). For ballistic missile-related technology, permission is required for eight years. This effectively grants the United States, Great Britain, and France a veto over most Chinese and Russian arms sales (an exception was made for Russia to complete the transfer of an $800 million S-300 air defense missile system to Iran in November 2016).

Why China Would Arm Iran

Beijing has not yet disclosed its intentions following the lifting of UN restrictions in October but a renewal of major arms sales to Iran would reflect increasing opportunities and reduced constraints. The key opportunity would be exploiting a new market for Chinese arms producers, seven of which rank among the world’s twenty largest weapons manufacturers. The Middle East is already China’s largest market, accounting for $10 billion in arms sales between 2013 and 2017.

As Iran’s supplier, China would have to contend with Russia, which has been in talks for orders worth $10 billion but could avoid competition from the United States and Europe, at least until EU embargoes expire in 2023. China’s comparative advantages include lower end-use restrictions, cheap products, a potential willingness to circumvent Beijing’s November 2000 pledge to follow Missile Technology Control Regime restrictions, and capabilities that surpass smaller states and even Russia in some areas, including advanced materials and shipbuilding.

While Iran has been able to effectively produce some items, such as drones, the Defense Intelligence Agency notes that Tehran “remains reliant on countries such as Russia and China for procurement of advanced conventional capabilities.” Beijing could profit by filling Iran’s conventional weapons shortcomings in several areas. In August 2015, China Daily carried a report highlighting the utility of the J-10 fighter for Iran, though rumors of a pending sale went unfulfilled. The more recent J-10C, widely marketed by Chinese firm AVIC, could also contribute to the modernization of Iran’s air force (which currently relies on 1980s technology). Moreover, Iran military analyst Farzin Nadimi assesses that Iran could seek Chinese products such as Type-022 fast-attack catamarans, YJ-22 anti-ship cruise missiles, Yuan-class submarines, and FL-3000N/HHQ-10 shipboard air and missile defense systems. Beijing could also provide Iran technical support in operating and maintaining these systems.

Escalating U.S.-Iran tensions and the U.S. administration’s desire to minimize the risks of a strong Iranian military could provide another opportunity for China. Chinese diplomats might resume their earlier practice of linking arms sales with other priorities, such as reduced U.S. arms sales to Taiwan, an invitation for China’s military to return to U.S. exercises such as RIMPAC, a cancellation of U.S. sanctions on the People’s Liberation Army, or an end to other U.S. Iran-related sanctions on China, such as those related to Chinese companies accused of illicitly shipping Iranian oil.

Even if such a deal could not be reached, Beijing could harness Tehran’s desire to boost its “anti-access/area denial” capabilities—which has likely been piqued following the recent crisis—to divert U.S. resources and attention from China’s neighborhood. This would weaken the current U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, which many Chinese analysts regard as focused on constraining Chinese military activities, just as arming Iran in the 1980s helped tie up Soviet forces. Support for such a stratagem in official Chinese circles is hard to gauge but perhaps a “strategic containment force” that can “drag the United States into the Middle East.” After all, the United States’ strategic assistance and strategic interactions with Iran are a critical component of its national security strategy.

A return to Chinese arms sales would also reflect diminished constraints. Beijing would have more flexibility in its approach because of Iran’s diminished pariah status (although this could return if Tehran follows through on threats to resume uranium enrichment) and the expiration of Security Council restrictions. The threat of U.S. sanctions, which contributed to China’s earlier restraint, would also likely be less effective today. Washington could respond by invoking domestic laws such as the 1996 Iran Sanctions Act and the 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act, but this option would probably only have symbolic value because unlike many larger civilian firms, Chinese arms suppliers have little or no presence in the U.S. economy. Broader sanctions would likely invite Chinese retaliation and be less effective due to Europe’s unwillingness to go along with them.

Washington’s Limited Options

One avenue to dissuade China from ramping up its arms transfers to Iran is persuasion. Aiding Iran’s military modernization would embolden Tehran and fuel conflicts across the region, which would endanger China’s stakes in stable energy markets, infrastructure projects, and the lives of Chinese nationals. This argument, especially if amplified by key regional actors, could result in China avoiding sales of systems perceived as particularly dangerous or escalatory. However, Beijing could calculate that if Chinese firms do not enter the market, then others will, including Russia. It is also worth noting that concerns about instability have not led China to crack down on illicit transfers to Iran in ballistic missile parts and dual-use technologies. A variation would be to pair arguments with concessions to entice Beijing, though some of China’s top “asks” (such as limitations on U.S. arms sales to Taiwan) would likely incur costs that outweigh the rewards.