Radical Republicans, Then and Now

Self-righteousness and inflexibility in the House will be just as destructive now as they were in the nineteenth century.

President Obama's ripping into Republicans earlier this month for trying to impose a “radical” program on the country drew criticism as being strident and intensely partisan. Whatever one thinks of the president's tone, however, there is no denying that the Republican Party, especially over the past couple of decades, has moved toward the Far Right. We see this in the serial political deaths, disillusionment or marginalization of that endangered species known as the moderate Republican. The next specimen in danger of being shoved aside is Senator Richard Lugar of Indiana, facing a challenger in the Republican primary with Tea Party support. The departure of Lugar, the ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would be a significant loss to well-reasoned Congressional consideration of foreign policy.

President Obama's ripping into Republicans earlier this month for trying to impose a “radical” program on the country drew criticism as being strident and intensely partisan. Whatever one thinks of the president's tone, however, there is no denying that the Republican Party, especially over the past couple of decades, has moved toward the Far Right. We see this in the serial political deaths, disillusionment or marginalization of that endangered species known as the moderate Republican. The next specimen in danger of being shoved aside is Senator Richard Lugar of Indiana, facing a challenger in the Republican primary with Tea Party support. The departure of Lugar, the ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would be a significant loss to well-reasoned Congressional consideration of foreign policy.

The New York Times highlights for us a different sort of challenge, but with the same underlying cause, facing presumptive GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney. As Romney shakes his Etch A Sketch and draws up positions for the general-election campaign, Republicans in the House of Representatives are putting him on notice that they would be uncomfortable with any of that moving-to-the-center stuff. And the House Republicans are making it clear they will assert themselves. “We're not a cheerleading squad,” says Representative Jeff Landry of Louisiana. “We're the conductor. We're supposed to drive the train.”

There once were Republicans who welcomed the label "Radical" and applied it to themselves. They first distinguished themselves as being the most ardently antislavery faction of the party. During the Civil War, they became dissatisfied with a president of their own party—Abraham Lincoln—for moving too slowly toward abolition of slavery. The Radicals' center of power was the House of Representatives, where they were led by Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania.

The Radicals' real heyday came after the war—especially after the election of 1866, when Radical-dominated Republicans achieved veto-proof majorities in both houses of Congress. Whereas overrides of presidential vetoes previously had been very rare, now Republicans repeatedly overrode vetoes by President Andrew Johnson of legislation governing Reconstruction of the South. It was the Radical Republicans who thus set the policy on Reconstruction.

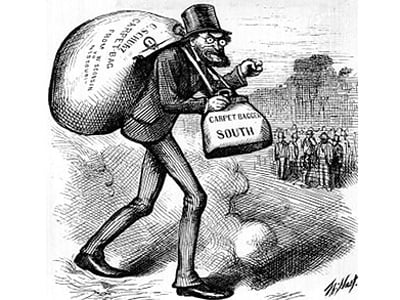

That policy treated the South like a defeated foreign power. It featured extended military occupation by federal troops and the banning from political life of those who had participated in the Confederacy. Civilian government in Southern states fell into the hands of Northern carpetbaggers and Southern scalawags. The system started breaking down amid economically related Republican setbacks in the mid-1870s and ended after the presidential election of 1876. Democrat Samuel Tilden won the nationwide popular vote, but the electoral vote was left hanging by confusion of the outcome in Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina. Under the Compromise of 1877, the electoral votes and the presidency were given to Republican Rutherford Hayes, in return for the withdrawal of the last of the occupying federal troops and certain other concessions to the South, marking the end of Reconstruction.

The Radicals' approach to Reconstruction had logic. However contrary secession had been to the U.S. Constitution, it had nonetheless occurred. The defeat of the Confederacy provided an opportunity to try to root out whatever had underlain both secession and slavery. But Reconstruction was a failure. The Compromise of 1877 was quickly followed by the enactment of Jim Crow laws throughout the South. A system of segregation and subjugation of blacks was established, most of which would not be dismantled until the 1960s.

The failure is related to some parallels between the Radical Republicans of the nineteenth century and those of today, and not just in having their power centered in the House of Representatives. Both have exhibited self-righteousness and an unyielding commitment to what they regard as just causes. Some of the causes, such as the abolition of slavery, are indeed just. But the self-righteousness has led in each case to destructive inflexibility. This has partly taken the form of clashes—emotional, hateful clashes—with a president. (The Radical Republicans of the 1860s tried to tie Johnson's hands with legislation inhibiting his ability to remove his own cabinet members; when he acted contrary to the legislation, the House impeached him.)

Over the longer term, the destructiveness has extended to the Radicals' own presumed goals. The segregated South that emerged from Reconstruction was certainly not what the nineteenth-century Radical Republicans were aiming for. A narrow, short-term attitude that emphasized a punitive treatment of white Southerners (especially white Southern Democrats) overlooked the reactions that such treatment encouraged. Given that Reconstruction treated the defeated Confederacy as if it were a foreign country, it is not surprising that some of the parallels with the present involve foreign policy. In particular, the myopia that corresponds to the attitudes that underlay policy on Reconstruction is an inability or unwillingness to understand how some assertions of American power encourage reactions that over the longer term are harmful to U.S. interests.