Assessing the F-35: How Failure Can’t Stop this Stealth Fighter

This fighter was meant to give America’s warfighters an edge over the competition, and if you ask the guys and gals flying it, that’s exactly what it’s done.

In recent months, a slew of bad press for Lockheed Martin’s long-troubled F-35 Joint Strike Fighter has once again made calling the 5th generation jet a failure culturally en vogue. From overt statements about the aircraft’s financial woes to newly announced tech issues causing “strategic pauses” in development and even an apparent lack of confidence in the aircraft coming out of the Air Force’s top brass, the Joint Strike Fighter program hasn’t faced such an uphill battle since the Pentagon first decided it wanted a single aircraft that could hover like a Harrier, fly supersonic like an Eagle, sneak past defenses like a Nighthawk, and land on carriers like a Super Hornet.

With all of this bad press, the inclination for some is to simply dismiss the F-35 program as an egregious acquisition debacle and nothing else. After all, the aircraft still can’t go into full-rate production because of a laundry list of issues, hundreds of delivered airframes may never actually be combat-ready, and the Air Force isn’t even sure they can afford to operate an F-35-focused fleet… With all of that piled up in the “con” column, it’s easy to see why some people never make it past those cons to begin with.

Assessing the F-35’s worth: Concept vs. Reality

The truth is, the F-35 isn’t a concept–it’s an aircraft–and that’s an important distinction. Concepts can usually be neatly filed under right or wrong; good or bad. Real things, by and large, aren’t so easily organized, and often (when it comes to new technologies) are as much a product of their challenges as their original design. Every groundbreaking military aircraft program has faced setbacks, and while no aircraft program has ever cost as much as the F-35 promises to in its lifetime, that cost doesn’t negate the real capability the fighter brings to the table. Let me be clear–this isn’t an argument in favor of the F-35 program, or even necessarily for the jet to keep its lauded position atop the Air Force’s priority list. It’s just an objective observation about what this fighter can do.

Again, as a concept, we can neatly file the intent behind the F-35 in the “good idea” category and the execution behind paying for it in the “bad idea” one–but in terms of this specific aircraft made of nuts and bolts, those distinctions aren’t quite as important as they are to the broader discussion. We can either take the significant leap in capability the F-35 offers and find a way to shoehorn it into a pragmatic model for spending as we move forward… or not. Lessons learned from the F-35’s acquisition debacle should certainly inform how America sources its next fighters (or anything for that matter), but in terms of the F-35 itself, only time travel could solve most of these past headaches… and time travel is one of the things Lockheed Martin has yet to deliver.

So let’s divorce ourselves from the emotion tied to dollar exchanges ranked in the trillions, forget about the frustration we’ve felt as the F-35 program has languished behind delays, and look at this fighter for what it was meant to be, what it is, and what it can be in the years ahead. Past failures in one column don’t necessarily mean future failures in another, after all.

The F-35 might be a horror story in accounting, but it’s also a massive success from the vantage point of its trigger pullers.

Asking for the impossible

The first studies that would lead to the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program as we know it began in 1993, with America shopping for a short take-off, vertical-landing fighter that could operate in the modern era.

Soon, the Pentagon took notice of other fighter programs in development and posited a theory: If America could find one airplane that could replace a whole host of aging platforms, it would shrink acquisition cost, streamline maintenance and operation training, remove many of the logistical headaches tied to operating a large number of aircraft in far-flung theaters, and make everyone’s day that much easier and less expensive. In hindsight, of course, those goals weren’t just naive, they may have been the program’s first major problem.

Lockheed Martin, the same firm responsible for the world’s first operational stealth aircraft, the F-117 Nighthawk, and the world’s first operational stealth fighter, the F-22 Raptor, would ultimately beat out Boeing for the Joint Strike Fighter contract, thanks to their track record in the field of stealth and impressive technology demonstrators.

Today, meeting the broad requirements of three American military branches and at least two foreign partners is one of the F-35’s biggest selling points… but in the late 1990s, it was akin to Kennedy’s announcement that America would put a man on the moon within the following decade. It was a good idea on paper… but nobody really knew how to make it actually happen.

“If you were to go back to the year 2000 and somebody said, ‘I can build an airplane that is stealthy and has vertical takeoff and landing capabilities and can go supersonic,’ most people in the industry would have said that’s impossible,” Tom Burbage, Lockheed’s general manager for the program from 2000 to 2013 told The New York Times.

“The technology to bring all of that together into a single platform was beyond the reach of industry at that time.”

But money has a way of making the impossible start to look improbable… and then eventually, mundane. The Saturn V that kept Kennedy’s promise about the moon was the most complex and powerful machine ever devised by man, and by Apollo 13–just NASA’s third mission to the moon–the American people already thought the rocket’s trip through space was too boring to watch (at least until everything went wrong). Likewise, building a supersonic, stealth fighter that can hover over amphibious assault ships sounded downright crazy, that is, right up until it was boring.

Making the impossible mundane costs lots of money

In order to meet the disparate needs of a single aircraft that could replace at least five planes across multiple military forces, Lockheed Martin chose to devise three iterations of their new fighter.

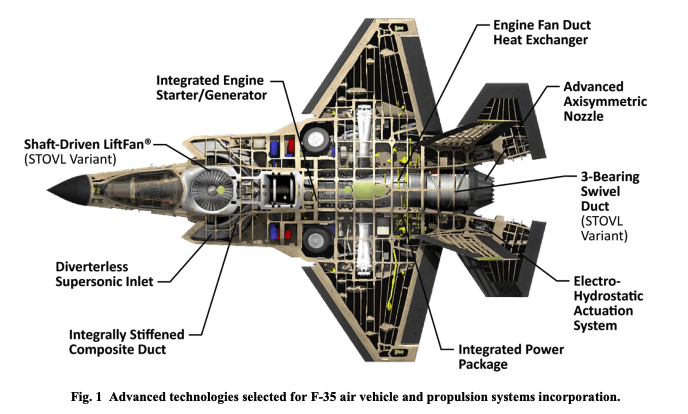

The F-35A would be the closest to what might be considered a traditional multi-role fighter–intended to take off and land on well-manicured airstrips found on military installations the world over. The second, dubbed the F-35B, would incorporate a directional jet nozzle and hidden fan to provide the aircraft with enough lift to hover and land vertically for use aboard Marine Corps amphibious assault ships or on austere, hastily cleared airstrips. Finally, a carrier-capable variant dubbed the F-35C would boast the greater wingspan necessarily for lower speed carrier landings, along with a reinforced fuselage that could withstand the incredible forces tied to serving aboard an aircraft carrier.

The plan was to leave as much about all three iterations as identical as possible, so parts, production, training, and maintenance could be similar enough regardless of the operating theater. That plan would prove infeasible almost immediately.

“It turns out when you combine the requirements of the three services, what you end up with is the F-35, which is an aircraft that is in many ways suboptimal for what each of the services really want,” Todd Harrison, an aerospace expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said.

Lockheed Martin’s team of designers began with the simplest version: the landing-strip-friendly F-35A. Once they were happy with the design, they moved on to the F-35B, which needed to house its internal fan right in the middle of the aircraft’s fuselage. As soon as they began work on the F-35B, it became clear that simply copying and pasting the F-35A design wouldn’t cut it. In fact, they were so far off the mark that it would take an additional 18 months and $6.2 billion just to figure out how to make the F-35B work–something you’d think might have come up prior to securing the contract.

This was the first, but certainly not the last, time a problem like this would derail progress on the F-35. To some extent, these failures can largely be attributed to poor planning, but it’s also important to remember that the F-35 program was aiming to do things no other fighter program had ever done before. Discovery and efficiency don’t always walk hand in hand–and to be clear, Lockheed Martin had no real incentive to make the Joint Strike Fighter work on a budget.

Concurrent Development: The dirtiest two words in aviation

The United States knew that what they were asking Lockheed Martin to deliver wouldn’t be easy. Stealth aircraft programs from the F-117 to today’s B-21 Raider have all faced a struggled balance between price tag and capability, but with so many eggs in the F-35 basket, the stakes quickly ballooned. With highly advanced 4th generation fighters like Russia’s Su-35 and China’s J-10 already flying, and their own stealth fighter programs in development by the 2000s, America was in trouble. The dogfighting dynamo F-22 was canceled in 2011 after just 186 jets were built, making the F-35 the nation’s only fighter program on the books. This new jet would have to be better than everything in the sky today and for decades to come… and it had to start doing it immediately.