Bad Call: Japan's Suga Was Too Optimistic About The Olympics

In the leadup to the Games, Tokyo had already entered its fifth wave.

Here's What You Need To Remember: Although Japan celebrated a record Olympic medal haul, Suga’s bet to bask in Olympic gold didn’t pan out. Whatever marginal political boost there was from the Olympics was dwarfed by public concern over the distraction of the government from its handling of the COVID-19 crisis.

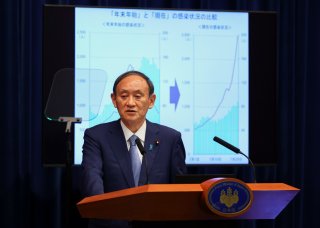

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s decision to hold the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games under the one-year postponement plan inherited from the Abe administration revolved around his need to face a Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leadership election in September and a lower-house election by October. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, proceeding with the Games was intended to protect Suga, who lacks a factional base in the LDP, from the threat of internal challengers.

The critical question was what level of infection control and vaccinations were needed to safely hold the Games without stretching Tokyo’s medical system? And what sort of measures would prevent spill over infections from the ‘Olympic bubble’? When pressed for details the Suga government insisted that Japan would hold a ‘safe and secure’ Games, evaded establishing definitive criteria for success and moved the goal posts when new information came to light.

The head of the Tokyo Medical Association, Haruo Ozaki, suggested in May that Tokyo needed to bring daily cases below 100 to safely hold the Games — advice that was ignored. A simulation presented at a Tokyo Olympic Organising Committee expert roundtable in June predicted that infections in Tokyo would increase to about 1000 per day in late August if the Games went ahead, compared with 800 a day if they were postponed or cancelled. A Tokyo Metropolitan Government monitoring meeting in July estimated that daily infections would reach 2400 by 11 August. These two scenarios were thought to be acceptable.

On vaccinations, Japan was too slow to reach anywhere near herd immunity before the Games. It was the slowest among the G7 to procure vaccines while its rollout ranked 33 out of 38 OECD countries when the Games opened on 23 July.

Medical experts questioned the integrity of the Olympic bubble in the lead up to the Olympics. With about 80 per cent of athletes, media and International Olympic Committee officials vaccinated and 30,000 COVID-19 tests conducted per day during the Games, the bubble was reasonably successful in limiting infections to the hundreds and preventing clusters.

But problems managing volunteers and local contractors, who commuted in and out of the bubble on public transport, were never resolved. Despite strict regulations, many volunteers didn’t undergo COVID-19 testing. The Japanese government made vaccination available to volunteers from 30 June — not leaving enough time for most of them to get a second dose. Olympics Minister Tamayo Marukawa was criticised for her ‘unscientific’ comments when she claimed that one dose would give volunteers ‘primary immunity’.

In the leadup to the Games, Tokyo had already entered its fifth wave. A fourth state of emergency was declared and spectators were banned. The record for daily infections in Tokyo more than doubled to a new high of over 5000 during the Games. Nationally, daily infections surged from a pre-Games fourth wave high of 7900 in April, to over 20,000 the week after the Games.

The number of COVID-19 patients in Tokyo awaiting guidance on hospital admission spiked from less than 2500 at the opening of the Games to over 13,000 as the Games closed. With medical facilities around Japan pushed to the limit, the government announced that only patients at high risk of developing ‘severe symptoms’ would be eligible for hospitalisation.

One reason for the surge of infections surrounding the Olympics was the spread of the Delta variant. Sample screenings of positive COVID-19 cases in Tokyo show that Delta accounted for less than 5 per cent of cases at the start of June, over 20 per cent at the start of July, over 60 per cent in late July and almost 90 per cent the week the Games closed in early August.

The Suga government and Tokyo 2020 organisers painted the rise in infections as unrelated to the Games, emphasising that cases in the bubble were ‘within expectations’. The government also argued that Olympic TV ratings were encouraging people to stay at home and decrease foot traffic. Yet contact tracing of cases between the bubble and the public is so politically sensitive that transparency was problematic. The government was found to have withheld information about an Olympic accredited official testing positive in Japan’s first case of the Lambda variant.

While the Delta variant, delays in the vaccine rollout and public fatigue with repeated states of emergency contributed to Tokyo’s surge in cases, the Olympics added fuel to the fire. Japan’s COVID-19 mitigation strategy relies on the public following voluntary government requests. Holding the Olympics, coupled with requests for people to stay at home under the state of emergency, resulted in confused public messaging and a diminished sense of urgency as people held Olympic viewing parties and crowded outside venues.

Despite the deterioration in its COVID-19 situation, Tokyo avoided a worst-case scenario of a global super-spreader event and a ‘Tokyo Olympic variant’ of the virus. Yet post-Olympics polling showed that almost 60 per cent of the public cited the Olympics as a contributing factor worsening Japan’s fifth wave of infections and two-thirds wanted Suga to resign by the end of his term in September.

Although Japan celebrated a record Olympic medal haul, Suga’s bet to bask in Olympic gold didn’t pan out. Whatever marginal political boost there was from the Olympics was dwarfed by public concern over the distraction of the government from its handling of the COVID-19 crisis.

Ben Ascione is Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies, Waseda University.

A version of this article appears in the most recent edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘Confronting crisis in Japan’, Vol 13, No 3. THis article was originally published in East Asia Forum.

Image: Reuters