Government Spending in the UK Helps Certain Voters More Than Others

As a result of spending decisions based on voter demographics, child poverty has risen over the past decade while pensioner poverty remained stable.

Governments face pressure in the years ahead to ramp up social security payments to help people affected by the coronavirus pandemic. However, in the UK, it has historically been voters who support the parties of government who get the money. My research, outlined in a paper awaiting full review, shows how this redistribution has contributed to inequality and poverty over the years.

Images posted by parents of the meagre food parcels they have been given in lieu of school meal vouchers have been a stark illustration of this trend.

As a result of spending decisions based on voter demographics, child poverty has risen over the past decade while pensioner poverty remained stable. Put simply, the Conservatives rewarded the pensioners (and high-income non-pensioners) who voted for them while levying cuts on the low-income parents who did not.

Electoral competition and redistribution used to be a simpler matter. Low-income voters could be expected to support left-wing governments, who gave them higher social security payments in return, while higher income voters supported right-wing parties, who rewarded them with tax cuts. Middle-income voters generally held the casting vote. Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives, for example, reduced taxes for middle and high-income voters while cutting social security payments for all those on low incomes, including pensioners.

The times – and electoral coalitions – then began to change. When New Labour came to power, electoral coalitions were no longer divided solely by income. Age and whether you were a parent began to play a role. New Labour did still increase taxes on the rich but didn’t increase social security payments for everyone on low incomes. Labour prime minister Tony Blair promised “to end child poverty”, while Gordon Brown promised to do the same for pensioners, but they did not promise to end all poverty. Child and pensioner poverty subsequently fell between 1997 and 2010 whereas poverty among non-parents actually rose.

More complex electoral coalitions would remain after New Labour left power. In a striking change from the Thatcher era, the Conservatives made it clear that they “would not touch pensioners” when they came to office in 2010. This commitment did not, however, extend to others on low incomes. Almost all of their subsequent social security cuts hit non-pensioners. Since 2010, pensioner poverty has remained stable whereas non-pensioner poverty has begun to rise. Child poverty, in particular, has been growing as low-income parents experienced cuts to social security.

One eye on the ballot box

These changes in poverty were driven by government spending decisions. Politicians always have one eye on the next election and they know taxation and social security policies are among the most powerful tools a government can use to win votes. Citizens reward incumbents with their vote when they feel like government decisions have made them better off. Indeed, David Laws, a Liberal Democrat cabinet minister in the coalition government, said he believed that the Conservatives did not cut pensions precisely because they viewed older voters as “a key electoral target”.

Identifying a voter base

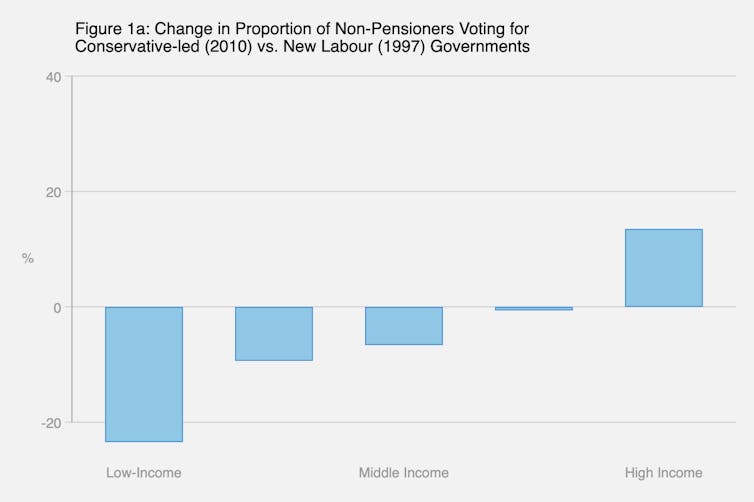

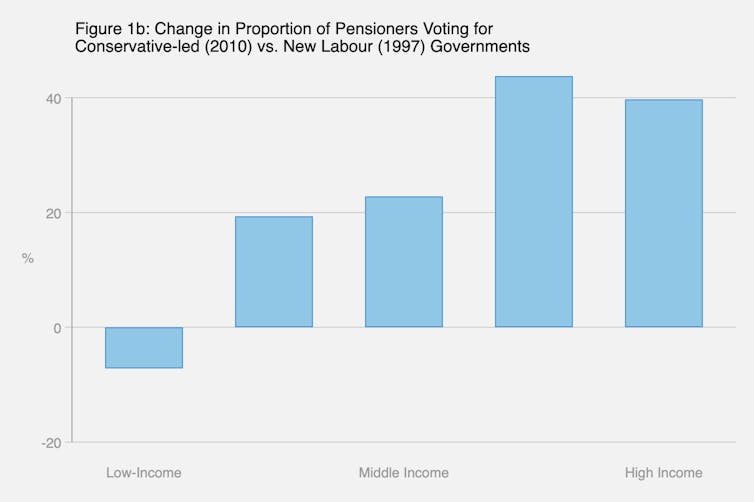

We can tell which voters are a priority for governments by looking at the electoral coalitions that brought them to power. To show how these electoral coalitions changed, I measured the difference between the proportion of pensioners and non-pensioners, by income level, that voted for the Conservative-led government in 2010 and Labour in 1997.

I measured votes for the Conservative-led government by weighing the votes for the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats in line with the number of seats each party won in 2010 (84% Conservative, 16% Liberal Democrat). Using votes only for the Conservative party in the calculation would also give almost identical results.

Nearly all pensioners were more likely to vote for the Conservative-led government in 2010 than they were New Labour in 1997. Of the working-age population, only those on high incomes were more likely to vote for the parties that ended up forming the coalition government. Middle and lower-income non-pensioners were less likely to vote for them.

The Conservatives then channelled money through the taxation and social security system to the groups that voted for them.

How electoral decisions shape lives

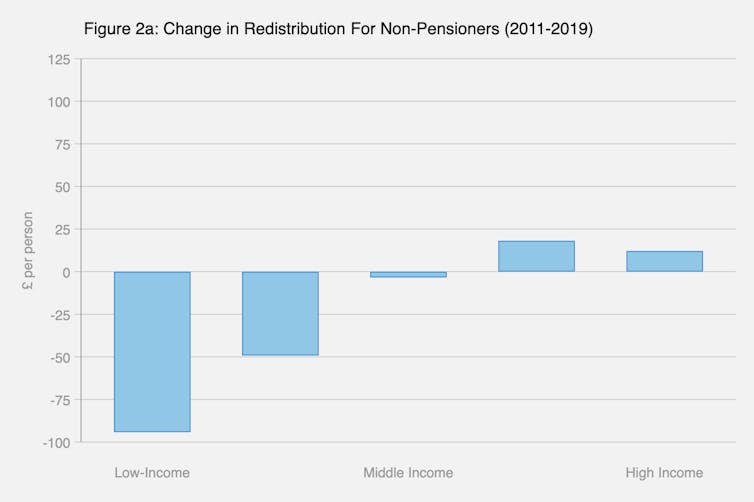

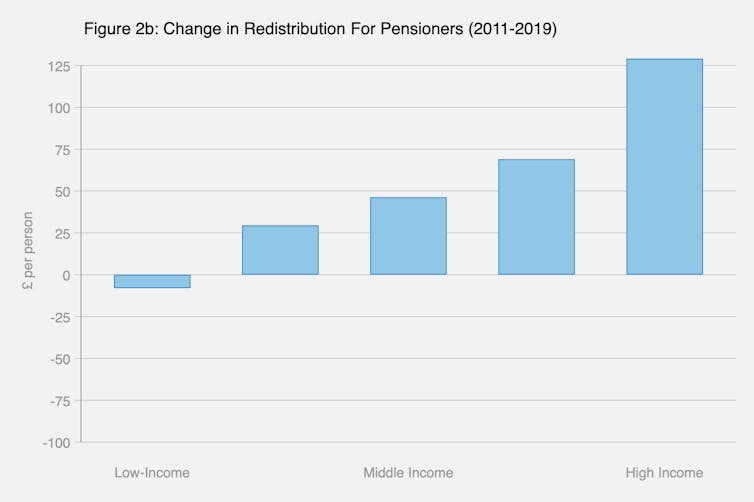

We can see the impact of this strategy when we look at the combined effect of government changes to taxation and social security payments on people’s incomes between 2011 and 2019.

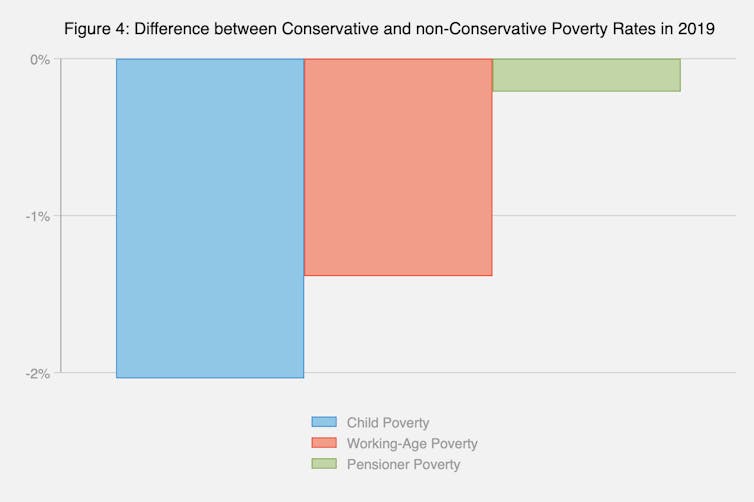

High-income non-pensioners who were more likely to vote for the Conservative-led government received tax cuts and, similarly, pensioners received higher social security payments. Middle and lower-income non-pensioners, who were less likely to support the Conservatives, had their social security payments dramatically cut.

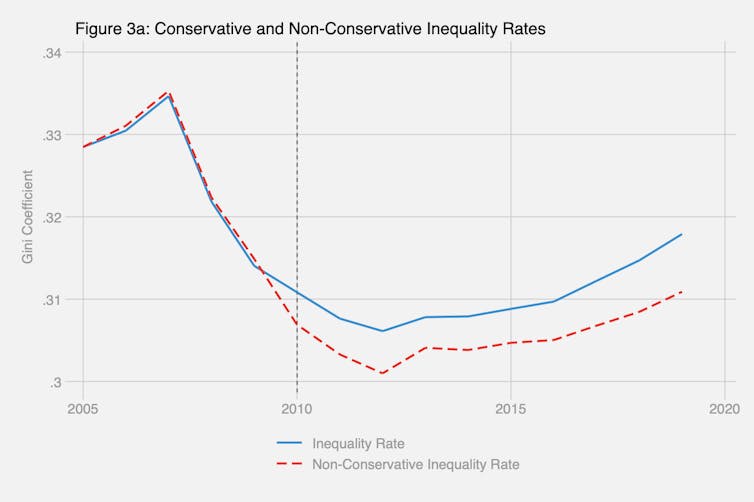

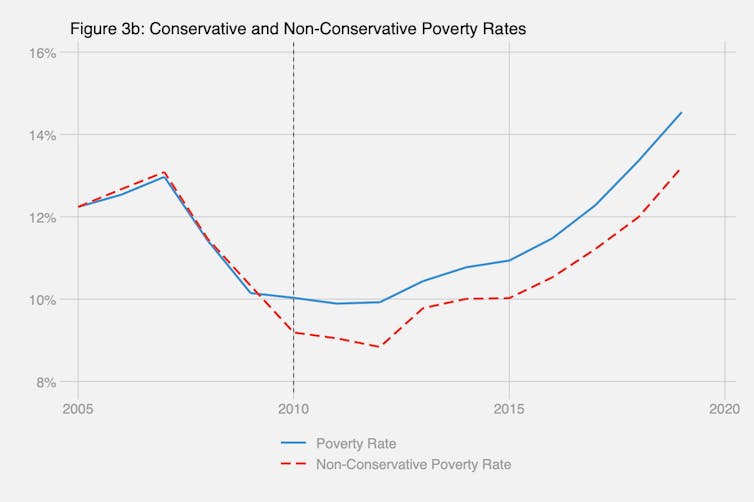

The effects of this redistribution were large. Tax cuts for high-income voters and social security cuts for low-income non-pensioners led to a substantial rise in inequality and poverty. By calculating what each person would have earned if there hadn’t been a change in government in 2010, I estimated the impact that electoral incentives had on the evolution of inequality and poverty. I found that, had there been no change in government in 2010, inequality would be lower and 784,000 fewer people would be in poverty.

Crucially, however, the Conservatives did not treat all low-income people alike. They had a clear electoral incentive to reward pensioners, who were more likely to have voted for them. Their reward was higher pensions that stopped pensioner poverty rising. There would, however, be a quarter of a million fewer children living in poverty had there been no change in government in 2010.

This research shows spending decisions often relate heavily to which voters brought a government to power. As much as we’d like to see a massive boost for people left destitute by this pandemic, post-crisis spending decisions may actually depend more on what these voters demand.

![]()

Jeevun Sandher, PhD Candidate - Department of Political Economy, King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters