How State Courts—Not Federal Judges—Can Protect Voting Rights

The U.S. Constitution gives the states’ primary responsibility for regulating elections, including federal elections.

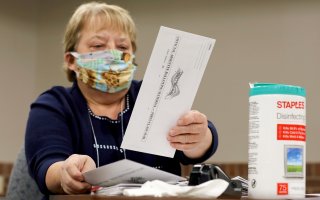

A jaw-dropping deluge of election-related lawsuits is already working its way through the nation’s courts, but some lawyers are taking a different tack than usual: ignoring federal laws and instead focusing on state constitutions and state laws, as interpreted by state courts.

That could be a smart move: The U.S. Constitution gives the states’ primary responsibility for regulating elections, including federal elections. Almost all the voting procedures at issue are matters of state law. And almost all state constitutions guarantee a right to vote.

Federal courts also handle voting rights cases. But in recent years, there has been an increasingly clear pattern of lower-level federal trial courts ruling to expand voting rights, only to see those rulings overturned by federal appeals judges, many of them appointed by President Donald Trump.

The research I conducted for my recent book, “Rethinking U.S. Election Law: Unskewing the System,” and my experience with a voting rights lawsuit in my home state of Tennessee, show that the state court path may be more effective at protecting voters’ rights – and a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling hints that way as well.

A new dynamic in federal courts

During the civil rights era and for decades afterward, the federal courts were the guardians of voting rights, a refuge from states’ discrimination. In recent years, though, that has changed.

Now, voting rights cases in federal court face uncertainty. For example, in Texas this year, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott declared that each county – some of which had already set up 10 or more drop boxes for voters concerned with mail slowdowns to deposit their mail ballots in – could instead have only one drop box. This one-per-county limit did not allow exceptions for counties with large populations or areas to cover.

In response to a lawsuit brought by the League of Women Voters and other voting rights groups, a federal trial court found that Abbott’s limit was an unreasonable barrier to voting – but a three-judge appeals court panel, all Trump appointees, overturned the lower court and upheld Abbott’s limit.

The same dynamic shows up in recent cases brought by Democrats in swing states like Wisconsin and Ohio. The Wisconsin case involved an attempt to extend deadlines to return absentee ballots. The Ohio case involved an attempt to expand the number of mail ballot drop boxes. In both cases, early federal trial court wins for expanded voting rights were overturned on appeal.

This pattern worries those like me who think it should be easier to vote – not harder – and especially so during a pandemic.

Similar cases with different results

That’s why I got involved in a state court lawsuit in Tennessee, which was one of only a handful of states that did not expand eligibility for absentee voting at the beginning of the pandemic. States that did so said they wanted to make it easier – and safer – for people to cast their ballots in local, state and national elections, including presidential primaries that were slated to happen through the spring and summer of 2020.

In May 2020, I helped a bipartisan group of voters in Tennessee file a state lawsuit seeking a judge’s order that the state expand mail voting in time for the August primary election. Around the same time, several national civil rights organizations filed a federal lawsuit seeking a similar order.

Though the cases were based on similar principles and sought nearly identical outcomes, they proceeded very differently. The federal lawsuit was assigned to a Trump appointee and proceeded very slowly over many months. The slow pace prevented the case from expanding absentee voting generally, and the court rejected claims to make it easier to distribute absentee applications and fix problems with absentee ballots. But the judge did issue a ruling in September allowing many first-time voters to vote absentee.

By contrast, our state court case resulted in a ruling that all Tennessee voters could cast their ballots by mail for the August election – and the decision came down within 30 days of the suit being filed.

Because the two cases pursued distinct legal strategies, these outcomes did not conflict with each other.

A strategy that is spreading

When we filed our suit, we did not make any claims under the U.S. Constitution or federal law. We kept our focus only on state law and the right to vote under the Tennessee Constitution.

We thought our case was strong enough without invoking federal laws, and we knew that invoking federal law could allow the state, which we were suing, to shift the case into federal court. We feared – and the outcome of the parallel federal case confirmed – that the case would be less successful before a federal judge.

In Texas, voting rights advocates are pursuing this same strategy in another attempt to overturn Abbott’s restrictions on drop boxes, by using only provisions of the state constitution and laws. That way they may avoid ending up in federal court, where the appeals court already ruled in Abbott’s favor.

Judges’ politics may make a difference

State courts may be less difficult for voting rights cases than federal courts are at the moment. Most federal appeals courts are now dominated by Republican appointees. More than 25% of federal appellate judges were appointed by Trump, a group that is conservative even by Republican standards.

These Republican-appointed judges show a marked pattern of ruling against voting rights plaintiffs, a recent study shows.

Of course, Republican appointees not only control the federal system’s top court, but with the swearing-in of Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court now has a lopsided 6-3 conservative majority for any post-election litigation.

By contrast, in some swing states, like Colorado, North Carolina and Pennsylvania, Democratic nominees enjoy a majority of the state supreme court. In other swing states, it may be more mixed, or tilted toward the GOP.

But even in those states, the judges are often elected, which may add another factor in a judge’s consideration. Public opinion may constrain judicial enthusiasm for decisions that could overturn the clear will of the voters. That contrasts sharply with federal judges, who have life tenure.

That popular opinion dynamic may have played a role in my Tennessee case. That was such a high-profile, politically charged hot potato that the Republican National Committee filed a brief opposing our case, even though Tennessee is a decidedly Republican state no matter how many people vote.

When our state trial court victory was appealed to the conservative-majority Tennessee Supreme Court, that court did trim back the scope of our win, but not by much. It allowed mail voting in November for anyone who has an underlying medical condition making them vulnerable to COVID-19, or who is a caretaker or co-resident of such a person. Together, those groups cover more than two-thirds of Tennessee voters.

Ending up in federal court anyway?

Of course, no strategy is foolproof. Even if advocates carefully focus on making claims about state laws in state courts, there is always a chance the case could end up in federal court anyway. The other side could complain that the state court’s ruling violates federal law or the U.S. Constitution.

That’s what happened in Bush v. Gore in 2000, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Florida Supreme Court’s order for a vote recount violated the Constitution. That case ended Florida’s recount, effectively handing the presidency to George W. Bush.

The Pennsylvania GOP tried a similar move in October 2020, asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review a Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision extending mail voting deadlines. The federal justices declined to take the case by a split vote of 4-4, which lets the lower court ruling stand. But new Justice Barrett could conceivably break the tie and bring the state case under federal review. Perhaps sensing this opportunity, the Pennsylvania Republicans are trying again.

And on Oct. 26, the U.S. Supreme Court blocked the extension of mail-in voting deadlines in Wisconsin. Chief Justice John Roberts explained that the difference between the two cases was that the Wisconsin case came through a federal court, while the Pennsylvania suit came from state courts – which is where he said voting rights issues should be decided.

![]()

Steven Mulroy, Law Professor in Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Election Law, University of Memphis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters