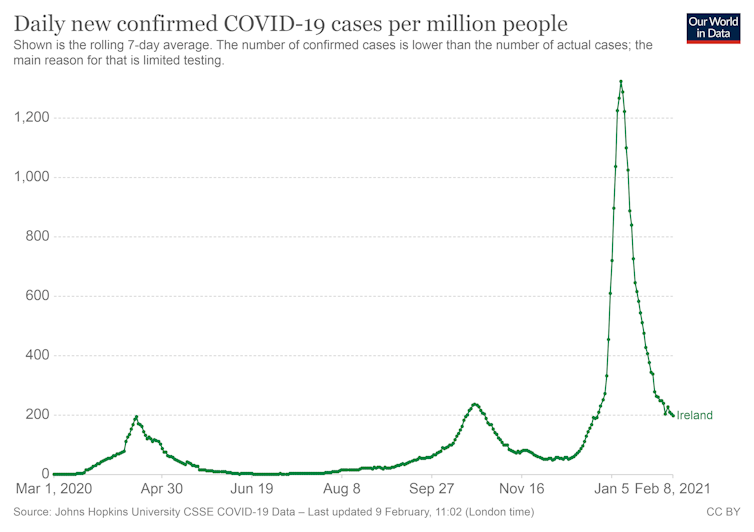

Ireland Turned Around One of the Biggest COVID Spikes in the World

One thing Ireland teaches us is even a limited amount of social mixing – which is what most people did – is enough to allow COVID-19 to re-erupt.

Ireland had the fastest and highest spike in cases in the world in January. This happened because, in early December, confirmed cases in the community were deemed to be low enough to allow some easing of restrictions. At that stage, Ireland had the lowest incidence of COVID-19 in Europe, which had been achieved with a second lockdown in November. Restaurants and non-essential retail were opened, and households could mix in a limited way.

People began to meet again, both outside their homes and inside. Despite many warnings about household gatherings, as Christmas approached it became clear that case numbers were rapidly rising, followed by hospitalisations, ICU admissions and, sadly, an increase in deaths. The reason was simple: too much contact between people. COVID-19 is a seasonal virus that spreads in winter – just like any other respiratory virus – because we are indoors a lot.

Irish people love Christmas and they had been through a tough lockdown in November. One thing Ireland teaches us is even a limited amount of social mixing – which is what most people did – is enough to allow COVID-19 to re-erupt.

Timeline for a turnaround

The Irish government reacted quickly. On December 24, nationwide restrictions were reimposed, and by January 6, Ireland was back into one of the most stringent lockdowns in Europe. The party was well and truly over. Schools and construction sites were closed, click-and-collect for non-essential retail was banned.

On January 26, the government extended the lockdown until March 5 at the earliest. Four days later, it was announced that Ireland had more cases in January than throughout all of 2020.

The total number of COVID-related deaths on December 3 was 2,080. It rose to 3,621 on February 5. This means that almost as many people have died of COVID-19 in the weeks since early December than in the entire time up to that point since the pandemic began. The price of Christmas.

The restrictions worked. On January 11, Ireland had a seven-day moving average of 6,363 cases. And from that peak, it has fallen steadily. On February 6, this had hit 1,035 cases – a decline that is among the fastest in the world. The lack of contact between people is the reason for this.

Hammer blow

Ireland’s experience yet again shows how straightforward it is to bring case numbers down. The virus jumps from one person to another. If people don’t meet, or if they meet following all the guidelines (distancing, mask-wearing, limited time indoors, ventilation), viral spread is lessened dramatically and cases drop. Ireland is dealing a hammer blow to the spike, driving it into the ground. This achievement is something to be proud of.

The hope of the vaccination campaign is keeping everyone going, as is the prospect of summer coming when the spread of the virus will be substantially lessened. Being outdoors is well known to decrease spread. We must learn our lesson well and remember it next winter when we move indoors again.

A repeat of what happened last winter is highly unlikely, especially given the mass vaccination programmes. But we can’t be too careful, especially with the emergence of new variants that are more transmissible, more deadly or better at evading the immune system.

Ireland must keep up with public health measures into the foreseeable future. This virus will exploit any weakness and the task now is to learn from mistakes and move to the next phase, with what has become the mantra of these times: cautious optimism.

![]()

Luke O'Neill, Professor, Biochemistry, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters