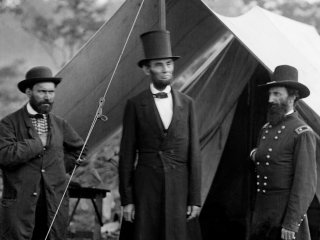

Three Crisis-Leadership Lessons From Abraham Lincoln

In persevering against a determined military enemy, President Lincoln left three noteworthy lessons about leadership.

In March 1861, as Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president, the United States faced its greatest crisis: its sudden and unexpected dissolution. Seven of the then 31 states had already voted to secede from the Union.

What he did in the following months and years made such a massive difference in history that David M. Potter, an eminent historian of the South, concluded years ago that if Lincoln and the Confederate president Jefferson Davis had somehow swapped jobs, the Confederacy would have secured its independence.

The Union’s military victory in the Civil War was not inevitable; another, lesser leader may well have accepted a compromise with the South. As I discuss in my book “Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post–Civil War World,” Confederates attempted throughout the conflict to negotiate a peaceful coexistence between an independent slaveholders’ republic and the United States.

In withstanding this effort and persevering against a determined military enemy, Lincoln left three noteworthy lessons about leadership: When fighting a lethal foe on home soil, he expertly managed top politicians; related well with the people; and dealt clearly with the military as commander-in-chief.

Handling political allies – and foes

Lincoln built and led a Cabinet of great strength by accommodating dissent. He included the two men who had been his rivals for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 1860, William H. Seward and Edward Bates. He sought advice on military matters, with daily briefings from his commanding general, Winfield Scott. He also asked for input on political issues – including those as important as the drafting and publication of the Emancipation Proclamation.

While he welcomed differences of opinion, he did not shirk responsibility. On April 1, 1861, Seward proposed declaring war on various European powers as an attempt to reunite the country. Part of the idea involved putting Seward in charge of the war, effectively elevating the president to be a ceremonial figurehead above the fray.

The president’s reply was stark: If there was going to be a war, he would lead it: “I remark that if this must be done, I must do it.”

Lincoln also dealt deftly with conflicts presented by self-important colleagues. When Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, plotted to contest Lincoln’s nomination for reelection in 1864, the president elegantly nominated his rival to be chief justice of the United States, removing him from political contests.

Connecting with the people

Lincoln was equally deft at relating to the public, having developed a carefully crafted ordinariness over his 30-year career of political campaigning in Illinois. That included cultivating a reputation for accessibility. As movie viewers saw in Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film “Lincoln,” his White House was open to all visitors and petitioners.

On the president’s daily rides to and from his favorite summer retreat in Washington, the cottage in Rock Creek, he passed soldiers’ hospitals and contraband camps, where African American refugees from the South gathered. Poet and wartime nurse Walt Whitman witnessed Lincoln’s “eyes, always to me with a deep latent sadness in the expression,” projecting his awareness of the gravity of the crisis, and his honesty and humility.

In Lincoln’s reassurance of the people, he communicated a wider message about the purpose of the war: In a mid-19th-century world dominated by aristocracies and monarchies, only in the United States was it possible for a man of such a humble background to rise to be head of state. In his view, the insurrection of slaveholders jeopardized the survival of that experiment in democracy and social mobility.

Therefore, in his great speeches, he used familiar words and phrases from Shakespeare and the Bible to present fighting the war both as a sacred mission, to achieve God’s aims, and as a universal, ideological imperative: to save republican self-government for the world. Emancipation would further this aim: in the closing of the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln hoped “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Managing the military

Lincoln’s ultimate success as a leader during the Civil War depended on his relationship with the Army, especially with its commanders.

The previous U.S. war, the Mexican War of 1846-1848, had been troubled by President James Polk’s distrust of the political ambitions of his top generals. Lincoln sought to avoid that conflict by being patient and focused in his dealings with military leaders.

Lincoln understood that he and his generals were all dealing with circumstances far beyond anything their training and experience had prepared them for. Most of the generals’ earlier careers had been fighting Native Americans. Even in the Mexican War – in which his generals had served in lower ranks – the numbers of soldiers in any one command had numbered, at most, a few thousand. At the same time Lincoln knew the Confederates also labored under the same disadvantages.

Now these commanders were suddenly responsible for maneuvering armies of over 100,000 men against an entirely different foe. In this bewildering context, Lincoln’s message to his commanders was simple: Focus on the military objective of destroying the armies of the Confederacy, and let him work out the politics.

Lincoln overruled generals who strayed into politics. In July 1862, George B. McClellan responded to his defeat in the Seven Days’ Battles outside Richmond by telling the president to cease and even reverse moves toward emancipation, stating: “Military power should not be allowed to interfere with the relations of servitude.” Lincoln’s response was twofold: He sent a terse message telling the general to go back on the offensive, and informed the Cabinet he would issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Once the president found a general committed to his aim of defeating the Confederate armies – Ulysses S. Grant – he nominated him to head all the Union’s armies and then left the combat planning to him.

“The particulars of your plans I neither know, or seek to know,” Lincoln confessed to Grant in mid-1864, on the eve of a crucial campaign against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia that would likely decide the war – and perhaps Lincoln’s own reelection chances as well.

Even with the gravity of the crisis facing the United States, Lincoln wished to convey his absolute confidence in the man whom he had promoted to be the first lieutenant general since George Washington. “You are vigilant and self-reliant,” he assured Grant, “and pleased with this, I wish not to obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you.”

Ultimately, Lincoln successfully enlisted political rivals, generals and the people to support the Union cause and win the Civil War. In order to accomplish this great task, the president had to simultaneously inspire, delegate and establish clear lines of authority for those around him.

Adrian Brettle is a Lecturer in History at Arizona State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Wikimedia Commons