Why America Is Losing the Tech War with China

It is simply too late to try to suppress China. The United States must either spend seriously on research and development, along with industrial policy, or it will lose the race for twenty-first-century technological supremacy.

China Is Pushing Ahead on Tech, and It Shows

The United States and China approach AI differently. The trillion-dollar valuations of the great American technology companies mainly come from consumer entertainment. China, as Huawei’s Zhang said, has no time for poetry. Rather than guess when the machines will become sentient or when AI will replace human beings, China has focused on the automation of drudge work: inspecting parts on a factory conveyor belt, checking the bins near the coal face for foreign objects, detecting anomalies in machines, picking containers out of ships and placing them on autonomous trucks, and so forth.

China’s plan to assert leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution—the application of AI to production, logistics, and services—appears to be on track.

Except for large manufacturers who already maintain large-scale operations in China, American manufacturers have shown little commitment to Fourth Industrial Revolution technology. To my knowledge, the only U.S. manufacturing firms that have installed private 5G networks to support factory automation are General Motors (which made 2.3 million cars in China in 2022), Ford (which made 500,000 cars in China in 2022), and John Deere (which rolled its 70,000th Chinese-made tractor in February). These firms have joint ventures with Chinese manufacturers and can be considered auxiliaries of Chinese industry.

The trouble is that what is left of American manufacturing after the great decline of the 2000s often does not have the scale to realize the benefits of AI applications. The installation of private 5G networks does not coincide completely with AI applications; wifi and fiber optic cables can transmit information just as well in certain factory environments. But 5G has obvious advantages over cable-based communications in environments with fast-moving heavy machinery, especially in robot-intensive manufacturing, mines, ports, and warehouses.

According to a count by the European 5G Observatory, about sixty factories, ports, and airports have built private 5G networks, prominently including automakers like Volkswagen, Porsche, Saab, and Toyota. Again, most of the manufacturing and transport firms applying this Industry 4.0 technology have a major presence in China.

As a Western consumer technology, 5G has been a disappointment. As the Wall Street Journal headlined a January 2023 report: “It’s Not Just You: 5G is a Big Letdown.” With download speeds of about 150 mbps per second, moreover, American 5G networks are half as fast as China’s. And some U.S. 5G networks have higher latency than the 4G networks that preceded them, making them less useful for applications like autonomous vehicles. Reduced spending on 5G infrastructure pushed Ericsson into a loss during the second quarter of 2023.

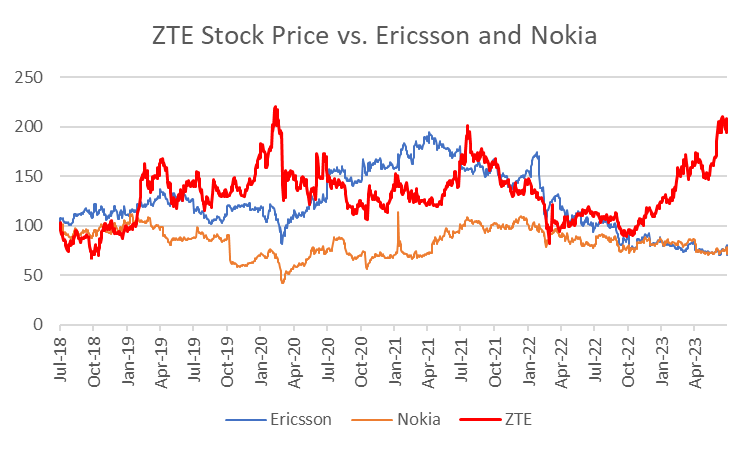

China, by contrast, views 5G as an industrial technology, and expects 5G2B (5G to business) to drive sales. The relative stock price performance of Western vs. Chinese companies contains some forward-looking information. Huawei, the largest provider of telecom infrastructure, is a private (employee-owned company) and has no listed stock price, so no insight can be gleaned there. But China’s number two telecom company, ZTE, provides a rough proxy for Huawei. Its stock price has doubled over the past five years, while the second and third-ranked global firms, Ericsson and Nokia, have lost about 30 percent of their market value (price performance calculated in U.S. dollars). That is noteworthy considering that the broad European market rose 23 percent between July 2018 and July 2023 while the Chinese market (CSI 300) is almost unchanged. American pressure has excluded the Chinese firms from the U.S. market and many European markets as well, but the Chinese firms dominate their home market and most of the Global South.

China thus has a distinct advantage in 5G broadband, a critical element in business automation. Transmitting large amounts of data (for example, thousands of photos of a factory conveyor belt per minute or real-time video of underground mining operations) is more of a bottleneck than chip speed. Last month, China was the first country to allocate spectrum in the 6GHZ band to 5G and 6G services, to promote “global or regional division of 5G/6G spectrum resources” and provide the groundwork to “promote mobile communications and industrial developments at home.”

U.S. spectrum allocation favors wifi over mobile broadband, allocating virtually all of the 6GHz band to “unlicensed use,” that is, Wi-Fi. As the industry website Lightreading observed, “the ruling represented a win for the cable industry and other Wi-Fi proponents ranging from Apple to Cisco. But for 5G network operators – which continue to argue they don’t have enough spectrum for high-bandwidth services like fixed wireless – the FCC’s ruling came as a setback.”

In other words, U.S. policies continue to favor consumer-oriented Big Tech over industry applications.

Telecom infrastructure and related applications have also buoyed China’s exports to the Global South, which have risen 50 percent since 2019 in ASEAN, nearly 100 percent in Brazil, and 250 percent in Turkey. Broadband has a transformational impact on countries with a high proportion of informal employment. It puts payment systems onto smartphones and opens banking and credit to previously marginalized people, and provides information and sales opportunities to entrepreneurs. It reduces the cost of delivery of services, including education and healthcare, and fosters new industries.

Because of all of these efforts, China in 2023 became the world’s leader in the largest manufacturing industry, automobiles, with $3 billion in global sales. High-tech manufacturing and economies of scale are likely to increase China’s edge. In 1908, Henry Ford defined an era of mass ownership of personal cars by pricing the Model T at $800, then America’s per capita GDP. China now produces electric vehicles with adequate range and power at around $11,000, just below China’s per capita GDP. China’s cheap but full-featured electric cars may dominate the low end of Europe’s auto market. Once China’s best-selling brand, Volkswagen’s market share has fallen, with annual sales down to 3.2 million units in 2022 from 4.2 million before the coronavirus pandemic. The benefits of 5G2B and artificial intelligence are thus tangible and visible: Cheaper industrial products, more efficient ports, deployment of automated vehicles, and so forth.

Meanwhile, in the West, how LLMs will drive profitability is less clear. Generative AI may find more lucrative uses in the future, especially in the automation of software, but how the existing technology justifies the trillions of dollars of additional equity valuation inspired by ChatGPT remains something of a mystery. OpenAI’s ChatGPT model meanwhile appears to have peaked as an object of popular curiosity, with a 10 percent decline in website visits in June.

As for present usage and estimates, the picture is sanguine. An Asia Times study noted that replacing every help desk employee in the United States with a chatbot would save a mere $1.6 billion a year, while replacing the bottom 25 percent of computer programmers by earnings would save just $2.5 billion.

Why Have U.S. Tech Sanctions Failed?

For several reasons, U.S. sanctions are ineffective in constraining AI development in China.

First, as noted, China’s home designs are competitive in industry applications, which typically require less computing power than LLMs and may already offer performance equivalent to the Nvidia and AMD offerings

Second, China’s SMIC can produce 7-nanometer chips, albeit with much higher costs and lower efficiency. It can certainly meet the requirements of China's military for 7-nanometer chips. These are probably quite small; existing military systems overwhelmingly use older chips, which are more robust and easier to harden, as the RAND Corporation explained in a 2022 study.

Third, Nvidia’s fastest AI chips are readily available in China through third-party sellers although at higher prices. Slower versions designed by Nvidia to stay within U.S. guidelines are still sold to China, although Washington reportedly may ban these as well.

Stopping Chinese firms from using American AI computing power via cloud services won’t accomplish much, according to US industry leaders. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy was asked by CNBC July 6: “One of the things the administration has floated is the idea that Chinese companies wouldn’t have access to kind of AI-grade cloud computing resources through hyper scalers, through cloud providers, like Amazon. Do you have a sense of how that would affect Amazon if Chinese companies couldn’t access AI scale computing on [Amazon Web Services]?” Jassy replied: “Well, the reality is that there are some very strong cloud providers who are Chinese cloud providers in China. So Chinese companies in China are going to have access to AI capabilities, whether they come from U.S. companies, European companies, or Chinese companies.”

Compete Seriously or Perish

U.S. limits on technology exports to China do not appear to have stopped or even slowed the rollout of the AI applications that have the greatest strategic impact. At the same time, restrictions on sales to China reduce the revenues of U.S. semiconductor companies and endanger their R&D budgets. In December 2019, the Defense Department vetoed a Trump administration plan to ban the export of high-end chips to Huawei on the grounds that the loss of Huawei as a customer would impinge on chipmakers’ ability to sustain R&D. President Donald Trump initially backed the Pentagon position, but reversed this later in 2020 after the coronavirus epidemic hit with full force.