Western Civilization's Life Coach

Mini Teaser: A new survey of Western thought begins in bombast and ends in triviality.

Arthur Herman, The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization (New York: Random House, 2013), 704 pp., $35.00.

ALBERT EINSTEIN is said to have recommended that “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” It is an injunction that Arthur Herman would have been well advised to heed when he embarked on the writing of his latest book, The Cave and the Light. But then oversimplification has been at the heart of Herman’s enterprise from the outset. Anyone who has already extruded works such as The Idea of Decline in Western History, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World, Gandhi and Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age, Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II and How the Scots Invented the Modern World is clearly not someone in whose imagination either nuance or complexity can be assumed to occupy much psychic space. Instead, Herman is a serial extoller, a panegyrist whose attention is periodically seized by one great man (Winston Churchill or Senator Joseph McCarthy, upon whom he lavished an admiringly revisionist biography) or a great people (the Scots) or a great institution (the Royal Navy, American business), which he then presents as the explanatory key to the success and dynamism of the Western world, even if we epigones in the West no longer necessarily understand our own great intellectual, moral, political and technical inheritance.

Even by Herman’s own grandiloquent standards, however, The Cave and the Light is in a class of its own. It is a monument not to the importance of historical thought but to his own hollowness. He begins in bombast and ends in triviality. He is a self-appointed life coach for Western civilization.

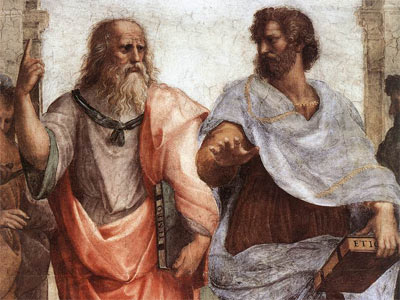

AT THE OUTSET, he asseverates, “Everything we say, do, and see has been shaped in one way or another by two classical Greek thinkers, Plato and Aristotle.” That such wisdom constitutes little more than the conventional thought inculcated in nineteenth-century British public schools does not seem to trouble Herman unduly. This is in part because his project is to refute those in the contemporary West who, in his telling, dismiss these thinkers as “dead white males” and the classics as having no future. Herman at times in his book takes a break from his breathless romp through Western history and philosophy to settle scores real and imagined with the global Left—in this case, the cynical teaching assistant’s tag for History 101, “From Plato to NATO,” is literally accurate. But while he is a political conservative (currently a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute) and an admirer of both Friedrich Hayek and Ayn Rand, even he might have thought twice about the “grandeur that was Greece, glory that was Rome” approach.

This is where the second part of his thesis comes in, the one already limned in his book’s subtitle, where Herman posits that the conflicts in Western civilization ever since ancient Greece have their roots in the dichotomy between Aristotle’s vision of what he calls “governing human beings” and Plato’s philosopher-king. To be sure, Herman’s heart is unquestionably with Aristotle, as he makes clear in his broad praise for Rand’s aversion to Platonism and also in his description of Hayek at the end of his life watching televised images of the overthrow of Communism in Czechoslovakia in 1989. “I told you so,” Hayek tells his son, to which Herman adds, “So had Aristotle.” Given his political views, this Aristotelianism should come as no surprise. “Today’s affluent, globalized material world,” Herman writes, “was largely made by Aristotle’s offspring.” But while he not only greatly prefers Aristotle, but also taxes Plato’s intellectual and spiritual heirs with virtually every political tendency and historical development in European and global history that he deplores, Herman nevertheless insists that “our world still needs its Plato.”

In Hayek’s terms, and—to careen vertiginously down the intellectual and moral food chain—in Rand’s as well, such a view is anathema. Late in The Cave and the Light, Herman approvingly quotes Rand’s assertion that “everything that makes us civilized beings, every rational value that we possess—including the birth of science, the industrial revolution, the creation of America, even the [logical] structure of our language, is the result of Aristotle’s influence.” Hayek’s view was far more nuanced (but then, compared with Rand’s, whose wasn’t?), and he was less concerned with praising Aristotle than with rejecting Platonism. For as his denunciations of solidarity and altruism in his book The Fatal Conceit make clear, Hayek viewed Platonism as a kind of owner’s manual for totalitarianism and saw socialism as Platonism’s twentieth-century avatar, much in the same way that Karl Popper did. But unlike his intellectual heroes, Herman insists on Western society’s need for Platonism as well as Aristotelianism. Though he returns over and over to Platonism’s intrinsic faults, and, by extension, to its economic fatuities and the world-historical crimes to which it has given rise, from Bolshevism and the Gulag to what Herman calls Plato’s “American offspring”—a term capacious enough to include Josiah Royce, John Dewey, Woodrow Wilson and FDR—Herman is adamant that Platonism remains key to the West’s identity, and a necessary corrective to Aristotelian dynamism, with its constant, stupefying potential for change.

This may seem contradictory (it certainly would have to Hayek and Rand, and surely cannot sit well with many of Herman’s colleagues at the AEI), but in fact it constitutes the core of Herman’s thesis. For him, it is the “tension” between the West’s Platonic “spiritual self” and its Aristotelian “material self” that has allowed the West to continue its “never-ending ever-ascending circle of renewal.”

For so proudly an anti-Hegelian, anti-Marxist writer as Herman, this tension he deems so essential bears a surprisingly close resemblance to G. W. F. Hegel’s idea, later taken up by Karl Marx and his twentieth-century inheritors, of the dialectic—that is, of thesis and antithesis that sooner or later are combined in a synthesis that represents either a compromise between the two initial philosophical or moral positions, or a combination of the best features of each. To be sure, Herman’s version of the dialectic is one that puts more emphasis on the creative tension between the two philosophical stances and less on the possibility of any enduring compromise or synthesis between them. As Herman puts it, while discussing what he argues was the English romantics’ doomed effort to reconcile the Platonic and the Aristotelian, “The creative drive of Western civilization had arisen not from a reconciliation of the two halves but from a constant alert tension between them.”

But Herman is inconsistent on this point. For example, in the concluding paragraphs of his book he asserts that this tension “inspired one breakthrough after another” in the clash between Christianity and classical culture, in what he anachronistically calls the “culture wars” between the romantics and the Enlightenment, and today, in the clash “over Darwinism and creationism or ‘intelligent design.’” He is explicitly making a case for what he calls the “indispensability” of both the Platonic and the Aristotelian worldviews in the creation of the Western synthesis that the “all-pervasive tug of war” between those worldviews has produced over the centuries. That tension and renewal, he argues, “are our [Western] identity.”

TO A HAMMER, everything is a nail. No one would deny that, in the Western tradition at least, the Greeks “invented” politics. But to go from this to saying that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle or of some tension between the two schools of thought as refracted down through the centuries really does stretch credulity. In fairness, such vast oversimplifications have always been the stuff of popular history, and popular history certainly has its place. If, for example, one wanted to recommend a book to an intellectually ambitious but not particularly well-read high-school sophomore, one could do a lot worse than Herman’s conspectus. It moves along jauntily, and its explanations, wild oversimplifications though they generally are, provide a basic framework for the future studies that, if undertaken and supervised properly, will challenge and overturn most of Herman’s facile binary summations. Herman himself points to this approach when he rather startlingly declares in his book’s concluding passage that the intellectual and moral tug-of-war dating back to classical times between Plato and Aristotle could also be called “yin and yang or right brain versus left brain.”

TO A HAMMER, everything is a nail. No one would deny that, in the Western tradition at least, the Greeks “invented” politics. But to go from this to saying that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle or of some tension between the two schools of thought as refracted down through the centuries really does stretch credulity. In fairness, such vast oversimplifications have always been the stuff of popular history, and popular history certainly has its place. If, for example, one wanted to recommend a book to an intellectually ambitious but not particularly well-read high-school sophomore, one could do a lot worse than Herman’s conspectus. It moves along jauntily, and its explanations, wild oversimplifications though they generally are, provide a basic framework for the future studies that, if undertaken and supervised properly, will challenge and overturn most of Herman’s facile binary summations. Herman himself points to this approach when he rather startlingly declares in his book’s concluding passage that the intellectual and moral tug-of-war dating back to classical times between Plato and Aristotle could also be called “yin and yang or right brain versus left brain.”

In doing this, Herman in effect vitiates his own most fundamental claims. There is no point in assaying a vast work of intellectual history if all one is actually doing is saying that in all cultures and, arguably, in all human beings, there is a tension between the rational and the irrational, the spiritual and the material, or the scientific and the artistic. Any of a thousand self-help books published over the last three decades can tell you that. And yet, reduced to its bare essentials, this is precisely what Herman ends up doing. According to him, “It is the balance between living in the material and adhering to the spiritual that sustains any society’s cultural health.” This seems more appropriate to a New Age retreat than to a believer in a very different, and in many ways far more mystical construct—a West that will never decline or be superseded because of that “never-ending ever-renewing circle of renewal” Herman invokes as if it were an undeniable fact rather than the hubristic, ahistorical fantasy that it actually is. It also raises the more interesting question of whether The Cave and the Light can properly be called a work of history at all.

Pullquote: To say that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle really does stretch credulity.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review