America Has Leverage with China that It Lacks With Russia

And Washington should use it to tilt great-power politics in its favor.

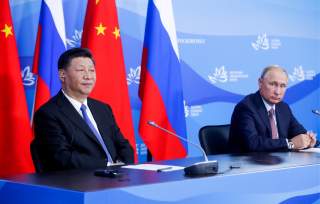

As Western sanctions ramp up, Russia is becoming increasingly, economically reliant on China, which provides Beijing with substantial leverage over Moscow. For its part, China still depends on Russia for access to some advanced armaments and as a diplomatic partner with which to counter the West, particularly in the UN Security Council.

Due to these imbalances, the U.S.-China-Russia strategic triangle is now more disadvantageous to the United States than at any time since the early 1950s. As former People’s Republic of China Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying observes, U.S.-China-Russia trilateral relations “currently resemble a scalene triangle in which the greatest distance between the three points lies between Moscow and Washington.” China now occupies the envious “hinge position” of having better relations with the other two poles than they do with each other, which Nixon and Kissinger exploited to great advantage. As a result, Angela Stent surmises that “If any country has a card to play, it is China.”

Proponents of Kissinger-style triangular diplomacy often forget that an underlying driver that engendered Chinese receptivity to Nixon’s overtures was Beijing’s long-simmering bitterness over intensive diplomatic engagement between Moscow and Washington dating back to the Khrushchev-Eisenhower summits of the 1950s. No one at that time would have claimed that the PRC was stronger than the Soviet Union, but after Stalin, the United States possessed leverage and a working relationship with the more pragmatic leaders in Moscow (particularly on managing the precarious nuclear arms race) that Washington lacked with the revolutionary Maoists in Beijing. Now, the situation is effectively reversed. The United States has substantial leverage over China, and Chinese leaders are more pragmatic than their Russian counterparts. While Putin is obviously very different from Mao, like 1950s and 1960s Mao, he defines Russia and Russian power primarily in opposition to the United States.

Finally, if Trump and Xi are able to achieve some kind of modus vivendi on trade and other economic issues, then it will deeply unsettle Russia. Moscow knows that at the end of the day, despite all the Putin-Xi bonhomie, the economic relationship with the United States is salient to China’s national interest. A prime example of this, is that as Russia has faced increasing U.S. sanctions since 2014, Chinese banks have been “largely unwilling to provide credit to Russian entities under U.S. sanctions for fear of the consequences for their dollar-denominated transactions and dealings with U.S. firms.”

The dawning realization in Moscow that Russia risks becoming a chip at the U.S.-China bargaining table may eventually spur Putin to rethink his policy of permanent confrontation with the United States. Perhaps then, conditions will be right for an American mission to Moscow akin to Nixon’s 1972 visit to Beijing. Until then, the real opening in the strategic triangle is in Beijing, not Moscow.

John S. Van Oudenaren is assistant director at the Center for the National Interest. Previously, he was a program officer at the Asia Society Policy Institute and a research assistant at the U.S. National Defense University.

Image: Reuters