Debunking Tucker Carlson’s Darryl Cooper Interview

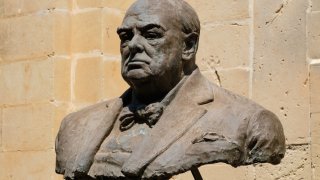

Recycled smears on Winston Churchill don’t hold up to scrutiny.

Debunking Tucker Carlson’s Darryl Cooper Interview

Last week, Tucker Carlson hosted the podcaster-cum-historian Darryl Cooper on his show. Though introducing him as the “best and most honest popular historian in the United States,” Cooper spent his time peddling ahistorical conspiracies and lies.

Gaining over 34 million views on X alone, such assertions need to be challenged. Most of all, his attacks on Sir Winston Churchill.

The Timeline

Cooper calls Churchill “the chief villain of the Second World War,” viewing him as “primarily responsible for that war becoming what it did, becoming something other than an invasion of Poland.” Such reasoning makes little sense, given the chronology of events.

When Great Britain issued its guarantee of Poland’s independence in April 1939, Churchill was out of office. Chamberlain was PM when Great Britain declared war on September 3, 1939.

Hitler’s Directive No. 6 for the Conduct of the War ordered planning for the invasions of France and the Low Countries in October 1939. Even on the date that Germany launched these invasions (May 10, 1940), Churchill was not made premier until that evening—after all attacks were initiated.

Cooper’s claims about the timeline of the conflict are erroneous. His subsequent point that Churchill wanted to go to war because “the long-term interests of the British Empire were threatened by the rise of a power like Germany” is ridiculous, as the British Empire had no borders with Germany.

The Warmonger

Cooper says, “Churchill wanted a war.” This is also untrue since Churchill did his utmost throughout the 1930s to wake up the world to the fact that she was walking herself into another global conflict. He certainly favored diplomatic talks instead of war but recognized that diplomacy could only be effective if the Western powers were armed. As he told the House of Commons in March 1934, “false ideas have been spread about the country that disarmament means peace.”

Writing for the Evening Standard in April 1936, he professed, “there may still be time. Let the States and people who lie in fear of Germany carry their alarms to the League of Nations at Geneva.” For Churchill, the avoidance of war was not merely a case of Britain and France ditching appeasement. It required worldwide commitment from many nations, who could then pressure Germany at the League of Nations,

I desire to see the collective forces of the world invested with overwhelming power. If you are going to depend on a slight margin, one way or the other, you will have war. But if you get five or ten to one on one side, all bound rigorously by the Covenant [of the League of Nations] and the conventions which they own, then you may have an opportunity of a settlement which will heal the wounds of the world. Let us have this blessed union of power and of justice: ‘Agree with thine adversary quickly, whiles thou art in the way with him.’

Churchill’s warnings were—of course—ignored. As he said in 1946,

I saw it all coming and cried aloud to my own fellow-countrymen and to the world, but no one paid any attention. […] There never was a war in all history easier to prevent by timely action than the one which has just desolated such great areas of the globe.

During one wartime meeting, Roosevelt asked Churchill his thoughts on the name of the global conflict. Winston responded, “The Unnecessary War.”

Operation Barbarossa

Nonetheless, Cooper continues by wrongfully claiming that Hitler “felt [he] had to invade to the east” out of fear of a direct Soviet threat or plan to capture Romanian oilfields. If one reads Mein Kampf, Hitler demanded German living space (or lebensraum) to the east. That was his actual reason.

Cooper then claims that Germany invaded Russia “with no plan to care for the millions of civilians and POWs” and “millions of people died because of that.” The Nazis planned these murders. One example was their starvation policy—Hungerpolitik—which was devised prior to Operation Barbarossa. Food exported from captured Soviet territory was to feed German soldiers, with widespread famines predicted. This aligned with Nazi racial theory that deemed inferior Slavs as “useless eaters” to be liquidated with poor rations.

That Cooper tries to imply that the Germans were concerned with not being able to feed Soviet POWs is genocide denial. For reference, seven months after the invasion of the USSR, some 3.3 million POWs were murdered by starvation, death marches, exposure, mass executions, and more.

Neville Chamberlain

Cooper accuses Churchill of “demonizing [Neville] Chamberlain” in 1940. Never mind that Chamberlain brought Churchill into his war cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty on September 3, 1939. Churchill also kept Chamberlain in his own cabinet. The day after Churchill became Prime Minister, he asked Chamberlain to be Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council.

They worked closely together, and Churchill took great interest in Chamberlain’s well-being throughout his battle with cancer. He pressed Chamberlain not to overexert himself. After his surgery, Churchill wrote to him, “I have greatly admired your nerve and stamina under the cruel physical burden which you bear. Let us go on together through the storm.”

Though Chamberlain resigned from his posts due to his failing health, Churchill sought the King’s permission to keep Chamberlain supplied with the Cabinet Papers. After Chamberlain died in November 1940, Churchill gave a beautiful eulogy. In it, rather than “demonizing” Chamberlain for appeasement—as Cooper falsely states—Churchill said,

History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days. What is the worth of all this? The only guide to a man is his conscience; the only shield to his memory is the rectitude and sincerity of his actions. It is very imprudent to walk through life without this shield, because we are so often mocked by the failure of our hopes and the upsetting of our calculations; but with this shield, however the fates may play, we march always in the ranks of honour.

Bomber Command

Cooper continues by saying he resents Churchill as “he kept this war going when he had no way to go back and fight this war. All he had were bombers.” Churchill was, by 1940, “going through and starting what eventually became just the carpet bombing; the saturation bombing of civilian neighbourhoods.” He accuses Churchill of launching these “gigantic scaled terrorist attacks” as it was the “only means that they had to continue fighting at the time.”

In 1940–41, the Bomber Command focused on targeted campaigns to hamper the German war economy, such as “oil supplies, communications and industry.” If one reads through the war cabinet papers, each week an updated resume was circulated on the Naval, Military and Air Situation. They clearly line out which targets were bombed. For example, the August 8–15 papers reference bombing attacks on key German infrastructure—including airframe factories, oil plants and aluminium works.

Given its small size, Bomber Command could not afford to waste its time on a policy of urban bombardment. As the Chiefs of Staff Committee recognized on September 7, 1940, “Our programme of air expansion cannot come to fruition until 1942.” It was not until the summer of 1941 that Churchill and the war cabinet seriously discussed using aerial bombardment against German cities as the primary purpose.

This was after Germany had engaged in a relentless eight-month bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, known as the Blitz. In addition to targeting infrastructure and the British war economy, much of this bombing was indiscriminate—designed to break British morale by inflicting as much damage and destruction as possible. The result was over 43,000 civilian deaths and a further 71,000 civilians seriously injured.

Nonetheless, Bomber Command did not engage in the policy of concentrated, widespread aerial bombing of urban cities until the spring of 1942.

Of course, this did not mean that civilian casualties hadn’t been incurred prior to this. The “Butt Report” in August 1941 highlighted to the war cabinet of the low accuracy of Bomber Command. The proportion of British pilots night bombing within five miles of the target was one in three overall in Europe. Over Germany specifically, it was one in four, with places like the Ruhr being 1 in 10.

Furthermore, a secondary aim of these (inaccurate) targeted raids was the destruction of German morale. As the Chiefs of Staff Committee noted in June 1941, Bomber Command’s targeting of German communication infrastructure lay “amongst workers’ dwellings in congested industrial areas, and their attack will have a direct [morale] effect on a considerable section of the German people.”

However, a simple analysis of the difference in tonnage dropped disproves Cooper’s ridiculous assertion of Britain committing supposed “gigantic scaled terrorist attacks” in 1940–41. Between June and October 1940, the RAF dropped a total of 6,000 tons of bombs against their fascist enemies. From March to June 1941, this had almost doubled to 12,000 tons. Germany, in contrast, dropped about 41,000 tons of bombs on Britain during the Blitz.