A Decade of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Middle East

China is still the largest foreign investor in the Middle East, and it is likely to continue to play a critical role in the region’s development.

Launched in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a global infrastructure and development strategy that aims to connect Asia, Africa, and Europe through a network of land and maritime trade routes—was a significant turning point in China’s foreign policy and has become one of the most ambitious and far-reaching development initiatives in history. It is also regarded by many in the West, the United States especially, as a not-so-subtle attempt by Beijing to reshape regional political orders in its favor.

In this light of this, it is worth considering the BRI’s impact in the Middle East. The region, home to a growing middle class, is home to several key international energy and sea trade routes. China’s heavy investment in the Middle East in recent years, including through the BRI, is thus of particular concern to Washington. Reviewing how such efforts have fared over the past decade may yield some interesting insights.

Why BRI Matters to the Middle East

The BRI is primarily a series of projects (comprising both traditional physical and digital infrastructure) designed to connect and integrate cooperating partners—cities, markets, and countries—across regions. Given this, a particular partner’s degree of connectivity plays a larger role than other factors, such as regime type or market share.

For Middle East countries, favorable geopolitical location and integration into key facets of the global economy play an essential role in China’s BRI framework. Consequently, China has developed a deep commercial presence in port cities and industrial parks that link the Persian Gulf to the Arabian, Red, and Mediterranean Seas. Myriad observers regard this presence as a way for China to secure its energy supplies, expand its trade, and gain a foothold in the region.

China’s engagement in the Middle East can be attributed to two primary drivers. First, it seeks to be recognized as a great power status domestically and by other states. The Middle East is a strategically important region, and China’s engagement is seen as a way to increase its influence and stake in the global order. Second, it aimed to secure its economic interests in the region through the BRI framework and continued access to energy resources on which it is heavily dependent. The BRI is thus a means for China to increase its channels for exporting goods, reduce trade friction, improve access to natural resources, build supply chains, and generate opportunities for Chinese companies to invest overseas and sell goods and services. To that end, over the past ten years, it has integrated the BRI framework with the Middle East countries’ national development strategies.

As the BRI is a long-term initiative that will continue to evolve in the coming years, Beijing will need to carefully assess the success and impact of its projects in the Middle East to make informed decisions on how to proceed. The success of the framework in the Middle East depends on several factors, including the economic and political stability of the region, the quality of the BRI projects, and the willingness of host countries to cooperate with China. More importantly, BRI projects are essential for underdeveloped Middle East states dependent on external creditors to establish critical physical and digital infrastructures. These projects are already in operation or are entering the second and third phases of development. Unless alternative creditors support further development, countries in the Middle East will continue to depend on and work with China.

Assessing BRI Projects in the Middle East

Currently, BRI projects span fifteen Middle East nations and include major infrastructural and digital projects on land and sea. The status of these projects varies, with some being planned, ongoing, completed, halted, or canceled, providing insight into the present overall situation of BRI. Developing a deeper understanding can be challenging, however, due to 1) deliberate opacity surrounding BRI projects on both the Chinese and host regional countries’ sides and 2) the sheer scale of the initiative, which spans large swathes of continents.

This lack of transparency is a major challenge for researchers and policymakers trying to understand BRI and its implications. Nonetheless, there is still a great amount of information available to consider. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) China Connects database, for example, provides a valuable overview of China's BRI investment and lending in the Middle East. The database also includes information on Digital Silk Road (DSR) investments, which can be understood to be the BRI’s technological component—a digital bridge-building project intended to promote a new type of globalization via digital trade, digital infrastructure, cross-border e-commerce, mobile financial tools, Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies (big data, digital currencies, cloud computing, and so on).

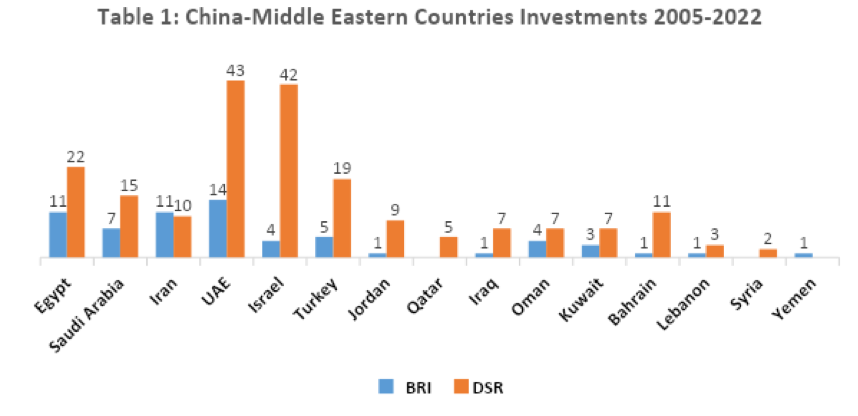

In any case, the IISS China Connects data demonstrates that China is investing heavily in the Middle East, with 266 BRI projects between 2005 and 2022 (see Table 1). Most of those are either ongoing or have been completed, and there are only a few projects that have been canceled or halted (see Table 2). This is a positive sign for China, showing that the initiative is gaining traction in the region.

Of note is what is being funded. The data shows that China is investing heavily in digital infrastructure in the region, which will likely continue in the coming years as Beijing seeks to expand its global reach. Chinese companies invested in 202 DSR projects (76 percent of the total investment) compared to 64 traditional physical infrastructure projects (24 percent). These investments are likely to have a major impact on the region’s economies and societies, and it will be important to monitor the impact of these investments in the coming years.

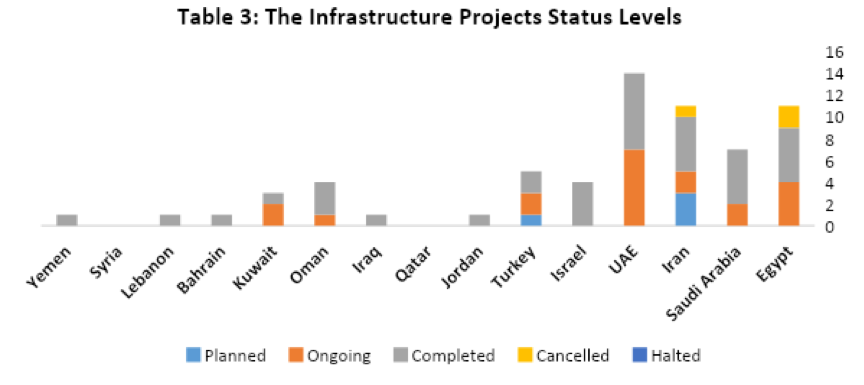

Breaking down by category, we see varying levels of progress. In regards to traditional physical infrastructure endeavors, out of 64 BRI projects, there are 4 planned projects, 20 projects ongoing, 37 projects completed, and 3 projects canceled (see Table 3).

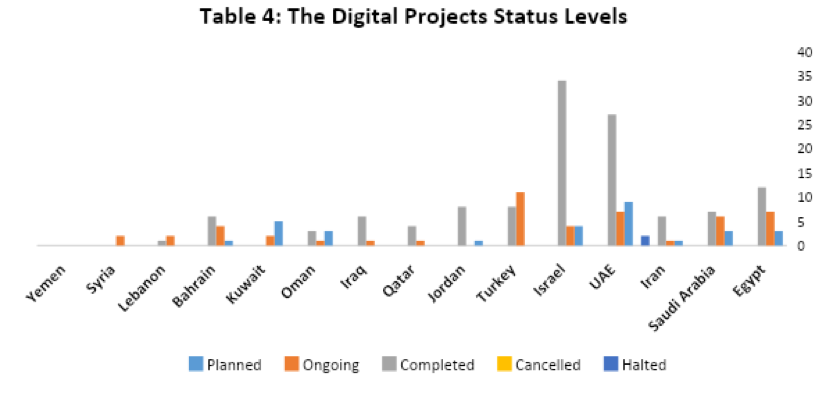

In regards to digital infrastructure efforts, out of 202 DSR projects, there are 29 planned projects, 49 projects ongoing, 122 projects completed, and 2 projects halted (see Table 4).

Looking closer at what types of digital infrastructure projects are being supported reveals that China’s most significant investment involves transferring technology, telecom, fiber optic cables, security information system, and financial technology (see Table 5).

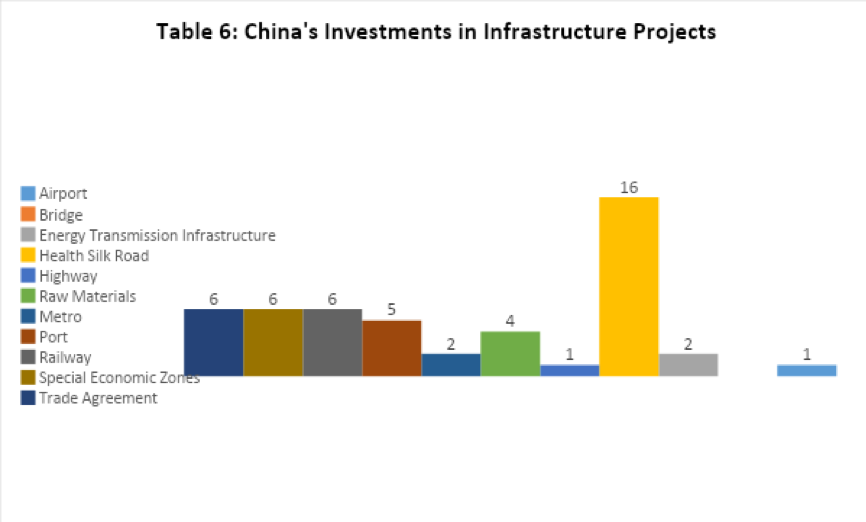

As for physical infrastructure, China's most significant investments are in ports, railways, Special Economic Zones, trade agreements, and Health Silk Road projects—i.e., projects related to improving public health. (see Table 6).

Drawing Conclusions

What the IISS China Connects database shows is that, out of the billions of dollars in loans and investments that China has to Middle Eastern countries since the launch of the BRI, most of these have been for digital infrastructure projects, such as telecommunications and broadband networks. This illustrates that contrary to the popular conception that BRI is wholly focused on physical infrastructure projects, there is significant demand for digital infrastructure.

That is not to say there isn’t any physical construction going on: roads, railways, and ports are certainly being built

At the same time though, the IISS database also shows that Chinese lending and investments in the Middle East have declined in recent years. This decline is likely due to several factors, including the global economic slowdown and the coronavirus pandemic.

Ultimately though, the IISS database is probably incomplete. Despite the BRI’s ambitious goals, there is little reliable information about how it unfolds. This is partly because there is no agreed-upon definition for what qualifies as a BRI project. As a result, projects that started years earlier are often counted, and the BRI banner hangs over a comprehensive and ever-expanding list of activities. By design, the BRI is more a loose brand than a program with strict criteria. This lack of clarity has made it difficult to accurately understand the BRI’s impact accurately. The result is competing interpretations of its effects: some have argued that the BRI is a major driver of economic growth and development, while others have warned that it leads to debt traps and environmental degradation.

What is certain, however, is that China is still the largest foreign investor in the Middle East, and it is likely to continue to play a critical role in the region’s development. The emphasis on digital infrastructure is something that most Western observers are perhaps unaware of and would do well to consider. In the meantime, as the BRI’s tenth anniversary passes by, China will take stock of its original agenda and make necessary adjustments to align with its current domestic and global priorities. The Middle East will remain a key region for the BRI, and it is evident that Beijing will continue its engagement for years to come.

Dr. Mordechai Chaziza is a senior lecturer at the Department of Politics and Governance and the Multidisciplinary Studies in Social Science division at Ashkelon Academic College (Israel) and a Research Fellow at the Asian Studies Department, University of Haifa. He specializes in Chinese foreign and strategic relations.

Image: Shutterstock.