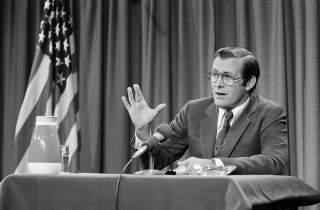

Donald Rumsfeld Recalls One of the Darkest Days of the Gerald Ford Administration

An excerpt from his latest book When the Center Held: Gerald Ford and the Rescue of the American Presidency.

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Donald Rumsfeld’s new book When the Center Held: Gerald Ford and the Rescue of the American Presidency.

In any presidency there is an inherent tension between the requirement to do everything reasonable to protect a President’s safety and a President’s understandable desire to meet and shake hands with fellow Americans. In September 1975, one year into the Ford presidency, two events brought that tension front and center in dramatic fashion.

Only a few weeks earlier, David Packard, a senior advisor who had been a founder of the Hewlett-Packard company and had served as the Deputy Secretary of Defense in the Nixon administration under Secretary of Defense Mel Laird, had come to the White House to discuss with the President a challenging but important issue. Given the unique circumstances resulting from the resignation of both a Vice President and a President in recent years, the issue he wanted to discuss was what would take place in the event President Ford did not survive his presidency. This was a critically important and a historically unique question. In our lifetimes, President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, and there had been concerns about President Nixon’s health during the long Watergate crisis. David Packard and I agreed it was important to raise these issues with the President: questions of command and control of America’s nuclear arsenal and what actions might have to be taken in the event of still another assassination or the incapacity of the President and the Vice President. Ford asked for a briefing on the matter and I had suggested that the Vice President have a separate briefing as well.

But these thoughts were not at the front of our minds, at least not then. The summer of 1975 had been filled with other issues and concerns. Betty Ford, for example, had appeared on 60 Minutes, talking openly about things most other First Ladies had avoided—such as her outspoken support for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. She also got quite personal, telling interviewer Morley Safer she would probably try marijuana if she were a teenager, that she’d seen a psychiatrist, and that “I wouldn’t be surprised” if her daughter told her she had had an affair. The unusually forthcoming First Lady sparked a sensation across the country and led a fair number of Ford aides to raise questions about her effect on the Republican Party’s conservative base. I, for one, believed you’d be howling into the wind by trying to tell Betty Ford what she could or could not say. Over time, as it became clear Americans across the spectrum admired Betty’s outspokenness and general zest for life, the worries eased.

The summer of 1975 also featured a continuation of some hardly unprecedented differences between various officials—Bob Hart- mann was suspected of leaking stories to the media against Henry Kissinger, which Kissinger, understandably, was not happy about. He was determined to identify the leaker. “He may have a legitimate gripe,” I advised the President in August, “but you do not want to have your administration get like Nixon’s did about that problem of leaks.”4 Vice President Rockefeller was trying to persuade people into backing various policy proposals he’d developed, which concerned key Presidential aides, including Alan Greenspan. Based on feedback I’d received from a number of quarters, I raised a caution flag to the President. The Vice President is enthusiastic and many key staff members were reluctant to disagree with the positions he takes, I said. “That is not a criticism of the Vice President, it is a criticism of the circumstance that you deal with as President because those people are afraid to deal with him—they are afraid to speak up when he is present, they are afraid to speak up even when he is not present and you just ought to be aware of it.”

There were lingering discussions and differing views concerning America’s intelligence-gathering activities, further reports of Governor Reagan’s political activities, and the advent of new crises. Added to those immediate tasks were: a looming financial crisis in New York City and a search for a new Supreme Court Justice to replace the retiring William O. Douglas. The President outlined his criteria for the post: quality, confirmability, age—so that the nominee could be there for a while—breadth on the Court so the Court did not have eight people of any one category, some diversity, and finally that the individual should be moderate to moderate conservative. (Ultimately, he nominated John Paul Stevens.)

These controversies and issues—important, to be sure—were promptly put on pause when we were quite suddenly faced with a considerably more pressing concern: President Ford’s mortality.

On Friday, September 5, 1975, President Ford was in the historic Senator Hotel in Sacramento, across from the California State Capitol building where he was scheduled to meet with the state’s new Governor, Jerry Brown. At approximately 10:00 a.m., he left the hotel with his Secret Service detail. He moved toward a sizable gathering of people, several rows deep, who had come out to greet the President. They were lined along the side of a path through the large park in front of the state Capitol. As Ford crossed L Street onto the Capitol grounds, he deviated from the plan—but in a way that hardly surprised anyone who worked with him. He moved immediately to- ward the many well-wishers who had gathered to see him and started shaking hands left and right.

The President was pulling—as he had on his trip to Japan—what is often called an unscheduled “grip and grin” session. This understandably raised the pulse of the Secret Service agents—as well as the concern of those whose task it was to keep the President on schedule—but it was certainly not a surprise. Gerald Ford was a man of the people. He had concluded it was worth the risks given the challenges the country and he had faced together—and overcome—to meet and engage personally with his fellow Americans. Further, very simply, he liked people and, given his midwestern friendliness, he truly appreciated their coming out to meet him.

As the President approached a stand of trees on the left, a woman in the second row of the crowd caught his eye. She was wearing, Ford later recalled, “an unusual red or orange dress.” The woman, he re- counted, “had gray-brown hair and a weathered complexion.” Ford assumed she was going to shake his hand, but he hesitated to greet her. His sensitivity and awareness was understandable. As a member of the Warren Commission, which had been assigned the responsibility to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Ford was fully aware of the dangers that lurked for prominent public figures surrounded by crowds. While he felt it was important to greet as many people as he could, he was still sensitive to the reality of the potential threats a President faces. Apparently something about this woman—perhaps her “unusual” brightly colored dress—stood out for him. Suddenly, when he was just a few feet away from her, he noticed she was gripping an object. It was a .45 caliber pistol, which she began to raise in the direction of the President.

The threat that September morning in California was thwarted quickly. An alert Secret Service agent beside the President had also seen the pistol. True to his training, he did not hesitate before pouncing on the would-be assassin. The quick-thinking team of agents then grabbed the President by his shoulders and moved him down and out of the possible line of fire. As he was being rapidly moved away toward the state Capitol building to safety, Ford turned and looked back just long enough to see a flash of red as several officers wrestled to the ground the armed woman who had set out that morning to assassinate the President of the United States.

From WHEN THE CENTER HELD: Gerald Ford and the Rescue of the American Presidency by Donald Rumsfeld. Copyright © 2018 by Donald Rumsfeld. Reprinted by permission of Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.