Get Ready, America: The Winds of Change Are Blowing in East Asia

"A rift between South Korea and Japan and flourishing ties between China and South Korea pose huge challenges to U.S. interests."

The ISIS and Gaza crises in the Middle East along with the conflict in Ukraine have pushed potentially momentous events in the Asia-Pacific this summer to the middle pages. Yet we are witnessing the beginning of a major reconfiguration of the East Asian geopolitical landscape that promises to have profound implications for, among others, the world’s three largest economies.

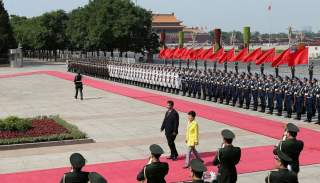

The visit of Chinese president Xi Jinping to Seoul early in July may well have cemented the trend. Xi became the first Chinese leader to travel to South Korea without visiting longtime ally North Korea—and young North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un has yet to visit Beijing nearly three years after coming to power.

State-controlled media in China billed Xi’s meeting with South Korean president Park Geun-hye as “ground-breaking,” claiming it struck at the heart of the trilateral pact that binds the United States, Japan and South Korea together. Meanwhile, in Seoul, the visit triggered media frenzy, with countless commentaries speculating over its long-term impact on the region.

Some observers were quick to play down its significance. For them, the status quo is set in stone: China will never abandon an alliance with North Korea that was signed in blood in the Korean War more than sixty years ago; South Korea will do nothing to weaken trilateral ties with the United States and Japan. But these comfortable blinkers obfuscate mounting evidence on the ground that South Korea is embarking on a concerted move away from its dependence on the United States towards a deeper relationship with China.

President Park’s tone towards Xi Jinping over the past year has been palpably amicable, marking her down as far more “pro-China” than even former left-wing president Roh Moo-hyun, who was routinely criticized for being anti-American, pro-China and Pyongyang sympathetic.

At an APEC summit in October of last year, Park reportedly quoted Xi a line from an ancient Chinese poem; a line she learned from a work of calligraphy Xi had previously gifted her. In contrast, she refused to even acknowledge the presence of Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe. They were sitting next to each other at the time.

Park’s warmth towards Beijing is of course rooted in economics and politics. China is now South Korea’s largest trading partner and largest export market for hi-tech goods. Crucially, a vitally important free-trade agreement between the two countries is gathering momentum with both sides pledging to sign a deal before the end of the year.

This agreement could underpin the RMB’s gradual transformation into an intra-Asian tradable currency, even as South Korea’s central bank continues to buy into U.S. treasury bonds. It may also pull mainland Asia away from the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership coalition-building efforts (a proposed free-trade agreement involving twelve countries).

Furthermore, the Park administration is giving serious consideration to participating in talks over a new China-led regional bank to fund infrastructure projects in Asia. The proposed Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank is seen by many as a challenge to the U.S.- and Japan-led Asian Development Bank.

Military ties between China and South Korea are also beginning to improve. Following Xi’s trip to South Korea, the two sides agreed to establish a direct hotline between their two defense ministers. Tension remains of course. A failure to finalize an agreement over the precise parameters of a partially overlapping, maritime exclusion zone resulted in the South Korean coast guard shooting dead a Chinese fishing-boat captain. And back in 2011, a South Korean coast guard officer died in a scuffle with Chinese fishermen. Remarkably, however, in the latest incident there has even been some criticism within South Korea of the coast guard’s use of live firearms. One can only imagine, by contrast, the level of national outrage had it been the Japanese coast guard that killed a South Korean national.

Goodwill between the Chinese and South Korean people has been on the rise, notwithstanding that maritime tension. South Korean soap operas enjoy phenomenal popularity on the Chinese mainland, while a mash-up dance video poking fun at Kim Jong-un has attracted millions of hits in China (much to the anger of North Korea).

It will take more than outlandish plot lines and viral videos to smooth the way to a formal Beijing-Seoul alliance. But driving South Korea and China closer together are their fragmented relations elsewhere in the region.

South Korea is deeply discomfited by what it perceives as attempts by Japan, under Prime Minister Abe’s stewardship, to whitewash its wartime past. A recent opinion poll found that Abe is now even less popular in South Korea than is Kim Jong-un. South Korea is equally uneasy about the United States’ deliberate strengthening of Japan’s military capabilities and regional influence—a blunt move to counter China’s growing influence in the region—which South Korea feels is buttressing Japan’s historical revisionism.

And it is also perturbed by signs of a rapprochement between Japan and North Korea. Abe has announced he will lift some economic sanctions on North Korea in return for its pledge to investigate the abduction of Japanese nationals by North Korean agents in the 1970s and 1980s.

U.S. indifference to these concerns has alarmed the conservative establishment in Seoul, which is otherwise one of the staunchest pro-American factors in the region. It has been rattled by the United States’ reluctance to revise its policy of reducing troop numbers and scaling down military commitments along the border dividing the two Koreas, while at the same time strengthening the hand of a more “militant” and “revisionist” Japan. Some are now pushing for improved relations with China in order to compensate for what they see as the “weakening” of the American security umbrella in the face of a belligerent North Korea and an increasingly “dangerous” Japan.

The warming of relations between China and South Korea coincides with Beijing’s harder line towards the North, which drifts further into isolation. While Kim was reported to have rashly snubbed earlier Chinese invitations to meet President Xi, it is now suggested that the North Korean leader has run afoul of Beijing after ordering the execution of his second-in-command, Jang Song-thaek, a former confidante of the Chinese.

The regime in Pyongyang appears fragile and erratic as it senses the South is making early preparations for its collapse. North Korea expressed its displeasure at Xi’s visit to the South by firing two mid-range missiles along its coast two days before he arrived. Xi reacted by reiterating China’s opposition to North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program.

Beyond its tabloids, Beijing’s language toward Pyongyang projects business as usual. However, the more time that passes without a formal meeting between Xi and Kim, the stronger the indication that China is beginning to view North Korea as a disposable hindrance, rather than an ally of convenience.

A rift between South Korea and Japan and flourishing ties between China and South Korea pose huge challenges to U.S. interests. Washington has failed to temper the personal antipathy between Park and Abe, and instead of attempting to repair the damage, Abe is fanning the flames by openly courting North Korea.

The United States needs to act swiftly to curtail any rising tensions that, if allowed to simmer untended, risk pitting South Korea and China against the United States and Japan, even while 30,000 American soldiers protect the South from the North’s aggression.

Washington ought to publicly welcome Beijing’s budding reassessment of its links with Pyongyang on the one hand, and warn Abe against any further overtures towards Kim Jong-un on the other. It must seize the opportunity to apply multistate pressure on the North. The majority of South Koreans still regard the U.S. military deployment as indispensable. The Obama administration cannot let doubts about American military resolve in other parts of the world seep into the Korean peninsula.

And it cannot allow Abe to upstage U.S.-led alliances with coalition-building maneuvers of his own. South Korea and Japan are mature democracies that have much in common, and are vitally allied with the United States. The interests of one should not override the concerns of the other.

Closer relations between Beijing and Seoul, if managed carefully, need not weaken Washington and its allies. However, if South Korea perceives the United States as reluctant to rein in ultranationalist tendencies in Japan and determined to reduce its defense commitments, its drift towards China will continue with damaging geopolitical consequences for the United States.

A carefully managed U.S.-Japanese-South Korean alliance guarantees U.S. interests in East Asia are protected. A lack of initiative and decisive leadership at this critical point could put these interests in danger.

Niv Horesh is director of the China Policy Institute, the University of Nottingham.

Hyun Jin Kim is an Australian Research Council fellow at the University of Melbourne.

Image: Flickr/Korea.net/CC by-sa 2.0