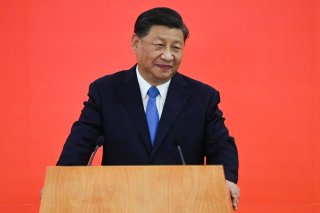

Has Xi Jinping Stopped Caring About China’s Economy?

Economic growth used to be sacred, but Xi Jinping is sacrificing it for greater political and ideological control.

Can Xi Stand It?

Will Xi’s drive to increase control prove too costly? Many observers have pointed to signs of dissent against Xi’s leadership within the party based on the unpopularity of some of his economic policies. For example, Premier Li Keqiang is sometimes said to be pushing for a separate policy line much more focused on economic stability and growth and countering unemployment. Other analyses have cited a few high-level dissenters such as property mogul Ren Zhiqiang or former party school professor Cai Xia.

However, as China expert Christopher Johnson has argued, the idea that Xi is under siege rests on faulty assumptions, such as that party elites do not broadly share many of his views or that the party’s tradition of factional conflict has continued unchanged under Xi. On the contrary, Johnson noted that “Xi appears to be hurtling toward a substantial victory at the 20th Party Congress.”

Public discontent over economic problems may pose a larger problem for Xi than intraparty dissent, although the two are often connected. In July, in a rare form of protest, hundreds of thousands of middle-class Chinese withheld mortgage payments on endlessly delayed or shoddily constructed homes. Earlier in the summer, hundreds of bank depositors who could not recoup their savings staged a high-profile protest in Zhengzhou, Henan. Many young Chinese, especially college graduates, are trying to find ways to drop out of the rat race for a shrinking number of good jobs, including by embracing “lying flat” culture or “run” culture, meaning emigrating.

Xi is betting, perhaps correctly, that greater political and ideological control will pay off. Zero-Covid controls have undoubtedly made protests more difficult. The policy also gives the party a strong argument for the superiority of China’s political system compared to countries that have failed to prevent large-scale deaths from the pandemic. Following regulatory crackdowns, almost all business leaders have “bent the knee,” at least publicly; many are promising large financial contributions to help the government reduce inequality or poverty. Although polling public opinion in China is tricky, surveys suggest that many Chinese are becoming more nationalistic and support Xi’s general policy lines, even if studying Xi Jinping Thought bores them.

In sum, Xi’s refusal to allow economic logic to drive policy is a considered strategy in service of political and ideological control. Xi never saw economic growth as an imperative the way his predecessors did, but the challenges posed by Covid-19 and the recent growth slowdown accelerated his abandonment of an economics-first governance strategy. Foreign observers and policymakers should not expect Xi to moderate his autocratic demands on the Chinese economy or society in his third term.

Christopher Carothers is a political scientist and the author of Corruption Control in Authoritarian Regimes: Lessons from East Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2022). He conducts research and writes on China, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. Dr. Carothers received his Ph.D. in Government from Harvard University and is affiliated with the Center for the Study of Contemporary China at the University of Pennsylvania.

Huan Gao is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Carleton College. She conducts research on urban governance, civil society, and spatial politics in China and has published scholarly articles in China Journal, Journal of Chinese Political Science, and China Report. Professor Gao received her Ph.D. in Government from Harvard University.

Image: Reuters.