How the ‘Global War on Terror’ Failed Afghanistan

The Global War on Terror has failed; but failure, they say, is a better teacher than success, and if the United States can learn from this failure and how it was generated, it may be able to avoid more disasters in future.

This feature of the United States has been made much worse by the U.S. system of political appointments to a wide range of official positions, on a far greater scale than in almost any other leading democracy. This reduces still further any possibility of independent advice from the permanent bureaucracy (insofar as that possibility ever existed). It also means that desire for future office (with the greatly increased private consultancy fees that result from this) leads members of think tanks and academia to carefully tailor their views to the dominant bipartisan consensus.

WE ARE now deep into the creation of a new bipartisan U.S. meta-narrative, that of global struggle with China. Its central theme is very familiar: that this is a fight to the death for the preservation of freedom and democracy in the world as a whole, in which U.S. leadership is essential. The sub-narratives built into the overall framework are also familiar: the exaggeration of the enemy’s ideological threat, global reach, geopolitical ambition, military strength, and moral evil. This exaggeration goes to serve the argument that the enemy threat requires the mobilization of U.S. resources, higher military spending, U.S. leadership, and U.S. presence across the globe, and alliances with enemies of China, however foul their regimes may be.

But because of its economic strength and dynamism as well as its ancient civilization and powerful nationalism, China cannot be worn down and defeated as the USSR was defeated. For one thing, the Chinese ideological threat does not really resemble that of Soviet Communism either in nature or in scale. China is not a revolutionary state and does not seek to create revolutions elsewhere. Its alternative example of authoritarian state-led capitalism can only be met by better performance of the U.S. state and economy at home—not as in the Cold War by support for “anti-communist forces” abroad.

In addition, a great many of the social and cultural problems now facing China—atomization of society, crass materialism, decline of the family, cultural decay, rampant socio-economic inequality, ruthless corporate power—closely resemble those affecting the United States; and some at least of the remedies being proposed in China also resemble those of U.S. conservatives (in the field of cultural values) and progressives (curbing corporate power and financial speculation). China as a culture, economy, and society is, therefore, more complex and less alien than the new Washington consensus would have it.

Moreover, China is with us for this age of the world (until perhaps climate change renders all geopolitical rivalries irrelevant). If the U.S. establishment locks itself into a dominant meta-narrative of fear and hatred of China, then it will be stuck with this for generations to come, together with its corrupting effects on American culture and democracy. If we wish to avert or at least mitigate this danger, a good place to begin is by examining how framing the U.S. response to 9/11 as the “Global War on Terror” contributed to the disasters that ensued.

Anatol Lieven is a senior fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and author of America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism. His website is Anatollieven.com. His latest book, Climate Change and the Nation State, appeared in an updated paperback edition in September.

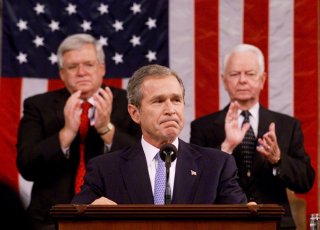

Image: Reuters.