ISIS is the New Pharaoh

Al Baghdadi could learn from the despot of the Passover story.

About 3,500 years ago, give or take a few centuries, an evil man ruled a desert kingdom.

He enslaved an entire people, worked them to death, even murdered their newborn children.

He was Pharaoh, the Egyptian king from the Biblical Book of Exodus, and a central figure in the story of Passover that Jews around the world commemorated Friday. Which historical king he was, or whether he even really existed, is irrelevant. He is simply Pharaoh, a prime character in a tale of slavery and freedom, bondage and redemption, which has reverberated down through the centuries.

In Pharaoh's day, there was Isis, the goddess of magic. Today, we have ISIS, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, which beheads people in the name of God.

At first glance, there could be little common ground between Pharaoh and ISIS. Even the Saudi Arabian royal family and their religious police aren't pious enough for ISIS, who has blown up ancient ruins in the name of Islamic purity. What would they have thought of a king who believed in magic and worshiped cat-gods?

On the other hand, Pharaoh would not have bothered with winning hearts and minds of ISIS supporters, or sponsoring democratic elections. To Pharaoh, ISIS would have been rebels who threatened his rule, and therefore were fit only to be run through with spears or run over by chariots.

But to the Hebrews in Exodus, Pharaoh must have seemed as monstrous as ISIS seems to us. Living under sharia law in ISIS-controlled territory is a nightmare, especially for non-Muslims or any Muslims that don't embrace their extreme version of Islam. But was it worse than working under Pharaoh's taskmasters, who "embittered their lives with hard labor, with clay and with bricks and with all kinds of labor in the fields, all their work that they worked with them with back-breaking labor"?

Pharaoh in the Book of Exodus is an odd figure, evil yet somehow tragic. A troubling passage in the Hebrew text states that God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that he would continue to oppress the slaves, even after God afflicted Egypt with locusts and lightning. The rabbinic interpretation is that God didn't force to do anything—which would have contradicted the notion of human free will—but rather that Pharaoh simply acted according to his personal inclinations.

And this is where Pharaoh and ISIS meet, because the single most defining trait of a Biblical despot and a fanatical terrorist group is their inflexibility. In the case of Pharaoh, it was stubbornness and an unwillingness to let mere slaves get the better of him. For ISIS, it is religious dogmatism so rigid that they cannot abide any other belief, even if it means their own destruction, or self-destruction through suicide bombing.

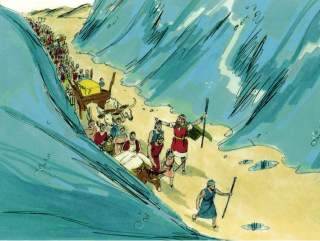

In the end, Pharaoh and his army are doomed by its own intransigence. Through the parted waters of the sea, they pursue the Israelites, until the waters closed back in and drown them. The brutality of ISIS, and their massacres in Paris and Brussels, have only succeeded in turning the world against them.

In the Passover story, the Angel of Death slays every Egyptian first-born, just as ISIS fighters—who are somebody's son—are struck down by U.S. drones and Russian jets.

And if there be a difference between us and them, consider that according to Jewish tradition, when the Hebrews rejoice at the death of the Egyptians, God rebukes them:

"How can you sing as the works of My hand are drowning in the sea?”

Pharaoh wouldn't have shed a tear. And neither would ISIS.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Image: Biblical illustrations by Jim Padgett, courtesy of Sweet Publishing, Ft. Worth, TX, and Gospel Light, Ventura, CA. Copyright 1984. Released under new license, CC-BY-SA 3.0