The Israel-Hamas War Has Killed the West’s Values-Based Foreign Policy

The deepest tragedy for many Western liberals, especially interventionists, is in facing the live global coverage of their doctrine’s collapse.

The mutual butchery in the Israeli-Hamas war only fortified the moral trenches of those who had already picked a side. However, an unspoken, yet almost palpable conclusion is emerging—moral confidence does not seem to provide clear, let alone feasible, policy prescriptions. This is particularly hard for some of the Western liberal foreign affairs scholars and practitioners to accept. Both the legitimacy and credibility of liberal foreign policy are the new victims in this war.

Long shaped by the advocacy of a “values-based foreign policy,” “humanitarian interventions," “responsibility to protect," the “rules-based order," and similar controversial slogans, the liberal interventionist audiences feel morally obliged to make sense of their governments’ foreign policy hypocrisy: fruitfully collaborating with the Middle Eastern dictatorships, yet condemning dictatorships elsewhere; protecting international borders here, but not there; defending civilians there, but not here, etc.

Leaders usually explain this hypocrisy away with the awkward claim that a liberal interventionist foreign policy cannot escape balancing values and the capacity to uphold them universally. Otherwise, the logic of the liberal interventionist perspective would be left wide open for realists’ assault.

For realists, values are balanced with a cold calculation of interests. This subtle difference helps liberal interventionists claim the moral high ground at home and abroad, since lacking the capacity to defend values always and everywhere is excusable. Prioritizing interests over values is not.

The constructivist take on international relations is equally damning for liberals. Constructivists claim values and interests are actually byproducts of perceptions and emotions. Hence, any policy discrepancy implies an inherent bias, not insufficient capacities: some lives and some borders are “more equal," i.e., closer to heart, than others.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict in general, and the current Israel-Hamas war in particular, present an incredible challenge to the legitimacy of the liberal interventionist perspective: the West must protect values such as Israel’s survival (especially since it is a sole regional liberal democracy), which is underlined by the memory of Holocaust. Yet, it must also protect the values of Palestinian human rights, their survival, and international law demanding the establishment of a Palestinian state.

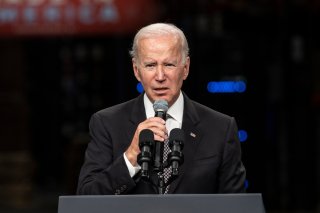

The capacity to do all is awkwardly questionable but ritually invoked every time the words “two-state solution” are uttered. They sadly resonate like a diplomatic “abracadabra”; the mystical word wizards use to do magic. An article written by Jake Sullivan, U.S. President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, in Foreign Affairs (echoed in Biden’s “post-war plan”) is the most recent example. Repetitive invocation without magical effect has worn off the phrase, now withering away just like the Palestinian “Right of Return” (to their 1948 homes, now in Israel).

On the ground, however, repeating the “two-state solution” abracadabra means pretending to have a solution while letting the “strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”—the quintessential realist position Thucydides summed up 2,500 years ago. One cannot but wonder whether, properly translated, invoking the “two-state solution” only hides the impotence of the cardinal liberal interventionist principle—the demand for the application of force to prevent mass atrocities.

One of the leading proponents of the “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine, Alex. J. Bellamy, admitted in his article on the 2014 war in Gaza that “…to some, it will appear highly controversial that I am even mentioning [the UN Security Council’s authority to apply military means to restore peace and security] in the context of Gaza.” Aware of the constellation of interests in the UN Security Council preventing an action to halt atrocities, he fell back to invoking “…peaceful settlement to this dispute along the lines established by the UN General Assembly and agreed at Oslo so many years ago” (i.e., the two-state “solution”) and reminding how “…much more needs to be done to marshal the resources at our disposal to the goal of protecting populations from atrocity crimes” (i.e., “lack of capacity”).

Contrary to liberal interventionists, radical Left (“campus”) liberals’ “woke” foreign policy relieved them from hypocrisy. For them, weakness proves righteousness. That Palestinians would destroy Israel only if they could does not worry them. To the contrary, they rejoice to the prospects.

Yet, the only destruction they contributed to has been the (further) political polarization in the West. Everyone is two clicks away from presenting undeniable evidence of the other side’s butchering: Hamas’ frenzied rampage in Israeli kibbutzim and Israeli industrial-style flattening of Gaza. The horrific images gush out, firing up self-righteous rage.

Both sides fortify their moral positions by ritually condemning the killing of enemy civilians. Even relativizing civilian deaths is not hard to find, for example among Israeli officials and pro-Palestinian student groups. Norman Finkelstein even legitimized the Hamas attack by comparing it with the 1943 Jewish Warsaw Ghetto Uprising against the Nazis.

Mainstream liberal hypocrisy over the capacity to uphold the human rights of both Israelis and Palestinians does tilt toward Israel. Underneath, and more importantly, conflicting strategic interests are vectoring, even if uneasily, toward Israel: pulling Arabs away from China and Russia; minimizing the anger of pro-Palestinian audiences globally; respecting the Israeli nuclear arsenal (and Israeli lobby); and blocking Iran’s influence.

Hence, the Biden administration is torn between giving Israel emotional-strategic satisfaction in pulverizing Gaza and limiting it before the Arab regimes implode under internal pressure to attack Israel—imploding being more likely than attacking. Iran stands to profit in the short term, one way or another. Biden's last push for “humanitarian pauses” failed to impress Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. However, it remains uncertain whether the primary goal was even Netanyahu or the public relations damage control vis-à-vis pro-Palestinian voters in the United States, leftist liberal Europeans, and many in the Global South opposing Israeli action in Gaza.

It seems that realist perspectives on international relations explain all sides’ policy choices, including the impotence of humanitarianism, much better than the alternatives. In his seminal article “Rationalist Explanations for War,” James D. Fearon presented the “credible commitment” theory of war. Simply said, if one side can credibly commit not to exploit a future opportune moment to decisively attack, the other side will abstain from attacking. Grasping this requires zooming out of Gaza today.

Observing the larger Israeli-Palestinian conflict from Fearon’s perspective, Palestinians must not only explicitly and publicly recognize Israel’s right to exist, but they must also credibly commit to the continued inability to attack Israel. The onus is on Palestinians simply because Israelis are stronger. The continuation of fighting is detrimental to Palestinian survival in the existing balance of power.

Even the “two-state solution” gives fragile hopes for peace. While Israel’s key concession within that framework would be physical withdrawal from strategically vital positions, the key Palestinian concession is only a verbal commitment to peace. What makes it credible? Changing your mind and attacking Israel when convenient remains possible. Israeli nuclear deterrence cannot substitute for strategic depth. In fact, its credibility depends on it, since the enemy’s close proximity turns nuclear deterrence into a suicidal threat many would welcome.

However, Hamas denies Israel’s right to exist. While Fatah officially does, some practices contradict that. Or, it accepts the right of Israel to exist, but not as a Jewish state, thus turning the form against the substance. Since Israel cannot be credibly assured of its safety, military domination supported by demographic expansion is the rational strategy if Israeli peace is only a Palestinian truce.

Successive Israeli governments operated within that mind frame: capturing as much territory as possible to secure strategic depth (1948, 1956, 1967, 1982); yielding to Egypt as much as needed to break the Arab unity (1979); damage control in Oslo after poorly handling the first Intifada led to establishing the Palestinian Authority (1993); and leaving Gaza to Hamas to break Palestinian unity and focusing on the land grab in the West Bank (2005).

Throughout all these episodes and under all governments, Israel maintained military occupation and increased its settlements in the West Bank to challenge Palestinian demographic domination. Since the “credible commitment” problem persisted throughout the peace process, Israelis always regarded the demilitarization of a Palestinian state as insufficient, demanding some form of military presence for oversight and control. This included keeping within Israel some strategically important corridors, zones, and larger settlements. Simply, full Palestinian sovereignty and Israeli security seem incompatible.

Despite the Obama administration’s continued protests, settlements kept expanding. In parallel, the growing Arab-Iranian rivalry brought the Arab states closer to Israel. The “Abraham Accords” formalized this rapprochement, but paid lip service to Palestinian rights, essentially marginalizing them. Regional and international diplomacy never stopped talking about Palestinians, whose oppression became a cause célèbre on Western campuses. It was becoming obvious, yet impolite to utter, that Palestinians are left to their misery in Gaza and to the increasingly numerous and aggressive Jewish settlers in the West Bank. The time was working against both Hamas and Iran.

Hamas’s decision to attack seems moral to its supporters, especially those safe from Israeli military reaction: continuing the armed struggle against the superior colonial occupier is admirable. Still, the rationality of the attack is questionable. Provoking Israel intensifies the grinding of Palestinian society until either the balance of power changes in the Palestinians’ favor or Palestinian society perishes. Since Hamas considered that the Palestinians’ perishing was becoming just a matter of time, it seemed rational to fight the future and burn the house down.