Modernizing America's Nukes: The Stakes of the Sentinel ICBM Project

Spurred by threats from China and Russia, America keeps modernizing its nuclear deterrent—but one troublesome missile is making it hard to stay on target.

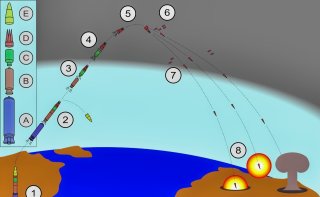

For decades, the United States has fielded a nuclear “triad” consisting of nuclear-capable bombers, ballistic missile submarines, and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). All three of these systems have prevented nuclear war and kept America and its allies safe—in large part because they’re tested and updated on a regular basis.

Nuclear-capable bombers such as the B-2 and B-52 help signal American intentions. Being visible, they assure our allies and deter our adversaries. Ballistic missile submarines are always at sea, undetectable, thus providing a continuous presence and an assured second-strike capability that can rain destruction on any target on Earth should the unthinkable occur.

ICBMs, due to their incredible speed and range, provide prompt long-range strikes from controlled environments and are nearly impossible to intercept. Stationed in underground silos, they are difficult to destroy and thereby complicate the designs of adversary targeteers, who know that it takes at least two nuclear strikes to destroy a single silo-based missile.

All three of these systems are being modernized. The Air Force is replacing the nuclear-capable B-2 stealth bomber with the next-generation B-21 bomber. The Navy is replacing the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine with the Columbia-class submarine. The Air Force is also replacing the Minuteman III (MMIII) ICBM—first fielded in the early 1970s and meant to be retired and replaced when Ronald Reagan was President—with the Sentinel ICBM.

Unfortunately, things are not going at all well with the Sentinel missile.

Cost Overruns and Schedule Delays

America stations its ICBMs in underground launch silos across 32,000 square miles of North Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, and Nebraska. A series of above- and below-ground command centers control the missiles. According to a recent Congressional Research Service report, the Sentinel will require less manpower than the MMIII, have more flexibility in payload, and improved survivability over its 1970s-era predecessor.

The Sentinel is, according to Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall, “probably the biggest thing, in some ways, that the Air Force has ever taken on.” The Sentinel program will acquire 659 missiles, with 400 deployed in 450 silos over the next decade. It initially had an estimated cost of $96 billion, with production slated for 2026—more than forty years after the MMIII was scheduled to be retired.

Unfortunately, the program is seeing significant overruns in cost and schedule. Last month, the Air Force reported that the program would increase to roughly $131 billion and maybe two years late in deployment.

Why is this the case?

Replacing the MMIII with the Sentinel is about more than swapping out old rockets for new ones. The infrastructure—much of which the Air Force built fifty years ago—requires renovation and, in some cases, to be built anew. According to a June 2023 Government Accountability Office report, the program entails not only producing new missiles and rocket motors but modernizing the missile silos, 7,000 miles of utility corridors, and the road network to missile fields within five states.

In addition, the Air Force must negotiate real-estate easements with hundreds of landowners. Moreover, Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the program, has noted other challenges to the program, including supply chain problems, lack of a trained workforce, and backlogs in security clearance processing for employees.

In January, the program’s cost and schedule overruns triggered a Nunn-McCurdy breach, forcing the Office of the Secretary of Defense to review the program and decide whether to restructure or cancel it.

Debating the Fate of the Sentinel

What has been the reaction to the Nunn-McCurdy breach? In the Defense Department, it has been one of determination and support. According to Lieutenant General Richard Moore of the Air Force, “Sentinel will be funded. We’ll make the trades that it takes to make that happen.”

In response to calls to do additional life extensions on the existing MMIII system, General Moore went on to say, “One way not to solve this is to think that we can just extend Minuteman III. There is no viable service life extension program that we can foresee for Minuteman III. It was fielded in the 1970s as a ten-year weapon.

Others—particularly those in the disarmament community—are already talking about scrapping the Sentinel and relying on the submarine-based nuclear deterrent alone or extending the MMIII until 2040.

Life extensions, as General Moore pointed out, are no longer a viable option for the MMIII, given the age of the rocket itself, as well as the potential impact of metal fatigue in the missile, as was possibly evidenced by the recent failure of an MMIII test launch.

In addition, eliminating the ICBM leg of the triad—which again creates targeting challenges for enemy nuclear forces—frees up enemy missiles to service other targets, including our ballistic missile submarine bases, military bases, or even civilian targets. In other words, retiring our ICBM force is a de facto force multiplier for enemy nuclear missiles.

Moreover, the current U.S. ballistic missile submarine force does not have the capacity to backfill or replace the number of warheads currently fielded in the ICBM field—and given our current shipbuilding capacity limitations, it would take the Navy well into the 2040s to build and field enough ballistic missile submarines to compensate for a retired ICBM force. In addition, as a recent RAND report pointed out, doing away with the ICBM force is simply a bad—and potentially destabilizing—strategy.

Finally, the current nuclear modernization project is not only about securing and defending our nation—it is about creating jobs for Americans in construction, electronics, plumbing, welding, machining, accounting, program management, or PhD-level physics and engineering. Indeed, it is the largest infrastructure project since the Eisenhower interstate highway system and can employ a similar number of jobs.

The United States must fully fund the Sentinel program. Its centrality to our nuclear deterrent demands it. However, Congress must, at the same time, be good stewards of the taxpayer dollar. If paying for the cost overruns means cutting other defense programs—including Northrop Grumman programs that are less central to America’s defenses than the Sentinel—then that is something Congress must consider.

The stakes are too high to do otherwise.

Doug Lamborn represents Colorado’s Fifth Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives and is chairman of the Strategic Forces Subcommittee.

Robert Peters is a research fellow for nuclear deterrence and missile defense at the Heritage Foundation.

Image: Creative Commons.