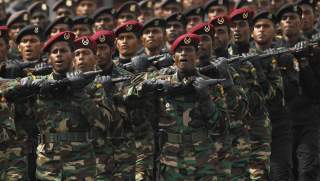

Sri Lanka's Presidential Election Reopens Old War Wounds For Tamils

Colombo’s past ethnic tensions have resurfaced with the election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Sometime in October of 2012, I found myself fortuitously sitting in the Indian Embassy in Beijing. The then-ambassador to China, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar asked me about how I liked living in Singapore; where at that time I was working with sports broadcasters ESPN STAR Sports.

Prior to his Beijing posting, Jaishankar, had previously served in Singapore as the top envoy (2007–2009). He was reminiscing about his days in Singapore and remarked that one of the best things that Singapore and Lee Kuan Yew had done was to create a system that fostered racial harmony and equality.

He drew an interesting parallel with Sri Lanka, where he had also served at a crucial period from 1988 to 1990 as first secretary. It was a time when the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) were tasked with fighting the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Mr. Jaishankar was the political adviser to the IPKF. His comparison between Singapore and Sri Lanka made for an interesting analogy.

He was deep in thought for a brief period and then mentioned that Singapore, like Sri Lanka, had three dominant races—the ethnic Chinese, the Malays and the Indian community, predominantly Tamils. Sri Lanka, too, had three major ethnic divides (in roughly the same ratio as Singapore)—the predominantly Buddhist Sinhalese, the minority Tamil and, of course, the third sect, Muslims (where religion is subcategorized as a race).

However, the Sri Lankan racial harmony story has been relatively non-existent. Especially, while Singapore’s Tamil population can boast of ministers in Tharman Shanmugaratnam and K. Shanmugam who have risen to the highest echelons of government, Sri Lanka has had an insidious history with its minority Tamil population.

Sri Lanka is known as teardrop island due to the unique shape of its landmass, which resembles a teardrop falling from India’s southeastern state of Tamil Nadu into the Indian ocean. But real teardrops linger for the Tamil population, victims of a brutal civil war.

Ten years ago, Sri Lankan forces stormed the northern provinces of the island waging a final assault on the LTTE, also known as the Tamil Tigers. This brought an end to the twenty-six-year bloody conflict, one where countless atrocities and death and destruction were juxtaposed with Sri Lanka’s tropical beauty.

In some ways, those wounds resurfaced with the recent election of Sinhalese strongman Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Sri Lanka is South Asia’s oldest democracy, but there is strong concern among the minority Tamil diaspora. Rajapaksa is the younger brother of Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was president from 2005 to 2015 and directed the assault on the LTTE.

The elder Rajapaksa is accused of war crimes committed against the Tamil minority as the United Nations estimates civilian casualties in the range of 70,000 deaths, however other reports point to the death toll being closer to 140,000. Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who also goes by the sobriquet Gota, wasted no time in appointing his brother Mahinda as prime minister. Even though term limits precluded the elder brother from coming back as president, Mahindra Rajapaksa is far from powerless. Both brothers as president and prime minister now wield executive power.

The younger Rajapaksa had a hand in the assault, as the former defense secretary under his brother. While Gota publicly stated that he wants to heal the festering wounds and work towards prosperity in the minority regions, the Tamils’ worries are far from assuaged.

The deeply-ingrained distrust goes back to the twentieth century, where the Sinhalese-dominated island imposed the Sinhala First Act, making Sinhala the official language in the country and sowing the seeds of linguism between the Tamil and Sinhala speaking population. There was an implicit understanding that Sinhala language and Sinhalese culture was viewed as native to the island, and everything else, especially Tamil, was an aberration to the tropical country.

In November, the Tamil diaspora overwhelmingly cast their vote for Gota’s main rival, the former minister Sajith Premadasa. A clear referendum on how the Rajapaksa brothers are perceived among the minority community.

Five years in the political wilderness, the Rajapaksa brothers’ return riding on the populist sentiment from the majority Sinhalese Buddhist voters, which make up close to 70 percent of the voter base, primarily in the southern parts of the country. The heinous Easter attacks in April gave the Rajapaksa brothers the political mileage needed to make the case of being a government that will not go soft on terrorism.

The fault lines run deep and the concern now is that these results will accentuate divisions along ethnic and religious lines, increasing suspicion towards the Muslim and Tamil minorities.

The tea leaves read a rise of chauvinistic and populist politics, closely mirroring various South Asian neighbors. While Rajapaksa’s speech made a plea to the Tamil and Muslim minorities to unite for the sake of a better Sri Lanka, his implicit message was perceived differently.

It didn’t help that Gota chose to have his inauguration ceremony at a Buddhist temple in the northern city of Anuradhapura. Legend has it that the site was built by Sinhala ruler Dutugamunu, who defeated the “invading” Tamil Chola King Ellalan and thus brought prosperity to Sri Lanka under Sinhala rule.

Gota himself has affirmed to uphold a strong Sinhalese culture centered around Buddhist heritage. Sri Lanka’s national identity has long placed Sinhalese Buddhism at the top of the totem pole. The constitution has enshrined these beliefs and thus at the highest echelons of government and military, there resides a level of belief in Sinhalese supremacy.

Tamil concerns are evident and during the last week of November, the diaspora in the northeast parts of the country gathered to commemorate Maaveerar Naal, a tribute to the fallen in the quest for Tamil liberation.

It remains to be seen if the second Rajapaksa government will ameliorate the woes plaguing Sri Lanka. At the outset, there is a bit of kleptocratic nepotism on display with family members being doled out key positions in government.

Also, it remains to be seen if Gota will avoid the mistakes his brother made by tilting towards Beijing while crooning for Chinese investments and falling into a debt trap; think Hambantota port, think white elephant.

Additionally, Gota Rajapaksa as a former defense chief and military man knows how to win a prolonged conflict and swiftly crush his opposition into submission. But the military man turned politician is now fighting on a different turf. And Gota knows only too well the battle of territories can be acquired, but the real war to win the hearts and minds of the disenfranchised can only be acquired through trust and not conquered through submission.

Throughout the Northeast, several of the Tamil population bear scars of a brutal twenty-six-year long battle between state and separatists. The physical wounds serve as a perfect metaphor and a reminder to the Rajapaksas. That wounds may heal, but the scars linger long after the war has been fought and won.

Akshobh Giridharadas is a former broadcast reporter covering business and international relations with Channel NewsAsia in Singapore. He has regularly published with outlets such as The Diplomat, the Observer Research Foundation, Inside Sources, and FirstPost on geopolitics, business and sports.

Image: Reuters