For Tajikistan, the Belt and Road Is Paved with Good Intentions

But so far it has proved disappointing.

Chinese investments are laying the groundwork for global economic development, but perilous obstacles remain.

Of the fifteen independent states formed after the fall of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan ranks lowest in human development. The country’s location at the epicenter of the Pamir Knot, a mountainous intersection where the Pamir, Karakoram, Hindu Kush and Tian Shan ranges converge, means that it faces towering obstacles to both political unification and economic growth.

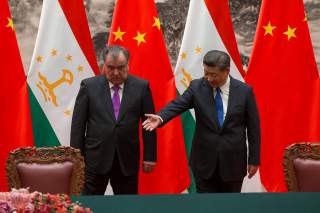

Fortunately—or unfortunately—Tajikistan is a crucial piece in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Although Beijing, backed by the United Nations, claims that BRI investments in trade-creating infrastructure projects will raise living standards for participating countries, to date, its ventures in Tajikistan suggest otherwise. The BRI is a mutually-advantageous opportunity—while China bolsters its access to foreign markets and diversifies supply chains, Tajikistan receives much-needed development infrastructure to facilitate economic development. However, both sides may not fully reap BRI’s potential benefits unless greater attention is given to inclusivity, remuneration, local employment and human rights.

Building without foundations of the necessary

BRI projects in Tajikistan range from roads and railways to pipelines and power plants, even including traffic cameras. China recently overtook Russia as the country’s largest source of foreign investment. But there are several reasons to believe that investments will not contribute to the economic development of Tajikistani society at large.

The first is that Chinese companies there hire mostly Chinese workers. Unlike other countries in the region, Tajikistan has no local content requirements that would mandate foreign firms to hire domestic labor. As of 2014, there were 82,000 Chinese workers in Tajikistan, and many Tajikistani workers were either paid less than their Chinese counterparts or not paid at all. Tajikistan is the most remittance-dependent country in the world, yet rather than fostering the local labor force, these practices are perpetuating dependence on external support.

A second indicator is that instead of paying loans back gradually, Tajikistan is signing away land and mining rights. In 2011, the Tajikistani government ceded 1,100 square kilometers of land near the Afghan border to China. Not only was the land along the Wakhan Corridor—historically one of the most strategic junctions for Chinese access to the Indian Ocean and West Asia—it also purportedly contained gold and uranium deposits. That same year, Tajikistan allowed Chinese farmers to till 2,000 hectares of arable land—a scarce commodity in such a mountainous country—near the Uyghur Autonomous Region of western China. It is widely believed, albeit unofficially, that these deals were made in exchange for “hundreds of millions of dollars” in debt relief.

Furthermore, in return for building two combined heat and power plants in Dushanbe in 2016, Tajikistan’s President, Emomali Rahmon, granted the contracting company, China’s Tebian Electric Apparatus (TBEA), exclusive rights to operate two gold mines. The TBEA will operate the two mines until it can recoup its $332 million investment. Essentially, China is relying primarily on its own companies and labor to build projects then extract resources, which minimizes long-term economic benefits for Tajikistan, such as local capacity building and labor force participation.

The third hindrance to Tajikistan's economic development is the government's demonstrated proclivity for white elephant ventures. In 2011, President Rahmon ordered construction on the world’s tallest flagpole, a $40 million undertaking. He then commissioned the region’s largest museum in 2013, the world’s largest teahouse in 2014, and the region’s largest theater in 2015. In 2018, when he returned from Beijing with $310 million in loans and grants, he announced that 230 million USD would go towards building a new parliament complex. In a country with a per capita GDP comparable to Haiti’s, these projects divert Chinese financing away from more crucial investments in areas like public services.

Lastly, Chinese loans encourage the regime’s corruption and human rights abuses. Transparency International ranked Tajikistan 161 out of 180 countries on its Corruption Perception Index and, according to Human Rights Watch, the government records citizens’ comments on social media, regularly arrests journalists and has administered nearly 100 known cases of torture since 2016. When corruption is rampant, politicians promote ostentatious projects—flagpoles, teahouses, pipelines—rather than fundamental investments in health and education.

True gold fears no fire

Ultimately, the BRI has incredible potential to raise living standards in developing countries and enhance long-term global economic cooperation, but only if it is sustainable. For China, this means carefully nurturing the initiative’s global reputation. Recent difficulties along the BRI should motivate Chinese state-owned enterprises to more constructively consider loan repayment schedules. Positive developments such as China’s agreement to form closer relations with the Paris Club creditor countries confirm that Beijing is receptive to financial norms of transparency and information disclosure. Ideally, China would become a full member, further supporting multilateral institutions, fair lending practices and addressing debt reconstruction issues.

Moreover, investing in projects with high expected returns and opportunities for local small and medium enterprises will ensure that loans can be repaid. In dealing with countries with proven track records of corruption, loans and grants must come with more stringent stipulations to mitigate risks for both parties. Publishing official loan data—project details, amounts and terms—would bring beneficial loans to light, alleviating international suspicions. After all, funding for white elephant projects does little for China’s stated aims of global economic development or the BRI’s reputation.

The over-reliance on Chinese contracting firms also hinders the BRI’s long-term feasibility. Fair competition over contracting licenses for BRI projects would improve the efficiency of Chinese firms, reduce project costs and invigorate the growth of local industries. Currently, 89 percent of BRI projects are contracted to Chinese firms, compared to just 17 percent of Asian Development Bank projects. Making the BRI more inclusive would facilitate economic development and improve its global stature.

Tajikistan, meanwhile, is at the intersection of three distinct corridors in the BRI. It is a critical piece in China’s geostrategic ambitions, and well positioned to negotiate greater domestic procurement in its dealings with Beijing. Ideally, local labor quotas would be a requirement of Chinese construction and mining operations. Chinese grants are a tremendous opportunity for Tajikistan to invest in its human development infrastructure. Building schools and hospitals rather than new parliament complexes would reflect positively on the BRI, encouraging continued foreign investment. Publicly and privately-funded training programs on BRI projects—demonstrated by many African nations—would enhance labor productivity, facilitate knowledge sharing between countries and brighten prospects for debt repayment.

A 2017 McKinsey report showed that BRI projects have generated employment for millions of African workers and created training programs across the continent. These examples, along with Kazakhstan and several Latin American countries, show that national development strategies and the BRI are not mutually exclusive; they can be aligned. The BRI is an extraordinary opportunity to alleviate poverty worldwide, but only if participating countries are built up, not paved over.

Sam Reynolds is pursuing his master’s degree in international relations from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, where he is the Washington D.C. Bureau Chief of the SAIS Observer. He is currently an intern with the Asia-Pacific program of the EastWest Institute.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EastWest Institute.