The Master Plan to Manage Iran: Keep Containing It

"The best way that the West can manage Iran is to keep containing it so the inherent staleness and corruption of the old guard either exhausts, or consumes, itself."

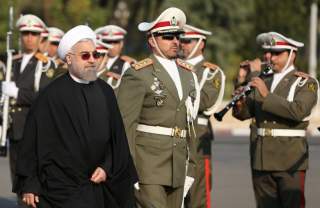

Iran’s nuclear program has been an ever-present fixture in Western political discourse since its full extent was first revealed in 2002. Yet, Iran’s nuclear quest began in the mid-1970s, when Iran was a pivotal U.S. ally in the Cold War. Then, as is likely now, Iran was pursuing a nuclear-weapon capability under the guise of a civilian nuclear program. Much like the Islamic Republic of Iran today, the Shah’s Iran vehemently denied this charge and claimed Iran was only pursuing nuclear energy in accordance with its rights as a signatory of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Today we are faced with a seemingly never-ending saga of on-again, off-again talks. Meanwhile the same figures, wholly part of the old guard of Iran’s clerical regime, continue to recycle themselves into positions of influence and dominate the political scene. Iran’s latest president, Hassan Rouhani, is no different.

Iran’s quest to become a nuclear power is rooted in the regional dynamics of the Middle East. The Shah envisioned his nuclear program in the 1970s as a response to the proliferation efforts of India and Israel. The Islamic Republic of Iran, as belligerent as it is, is maintaining a historical continuum that began with the Shah; that the national security of Iran is best served by the possession of a nuclear deterrent. The fact that the Shah’s regime was closely allied with Israel and America, a position dramatically reversed after 1979, makes this historical inevitability yet more acute today, since Iran’s closest regional ally is the embattled Assad regime in Syria. Iran now has few friends left and its economy is under siege by international sanctions.

What a historical reading highlights in this situation is twofold: Firstly, Iran is almost certainly seeking a nuclear deterrent—this is an inevitability of its regional politics. Deterrence has always been the driving logic behind Iran’s five-decade-long nuclear quest. Iran does not want a nuclear weapon for offensive reasons, and there is no rational motive for such an event. Secondly, the Islamic Regime is a rational actor, facing grave threats internally and externally (just like the Shah’s regime) and consequently seeking the extra leverage and security that a nuclear deterrent will provide. This is not a defense of Iran’s position, nor an acceptance of the Islamic Republic’s hostile and distasteful rhetoric. It is simply a statement informed by history. For Iran to launch an unprovoked nuclear attack is irrational and suicidal. If Iran used a nuclear device, whether directly or through a proxy like Hezbollah, it would suffer grave and immediate reprisals that would certainly mean the end of the Islamic Republic. There is no evidence in the last thirty-five years to even hint that the Iranian Regime is suicidal.

Each successive major regional event in the Islamic Republic’s history—from its grueling war with Iraq in the 1980s, to the Gulf War in 1991, to the regional battlegrounds of the Global War on Terror, and most recently, the collapse of the Assad regime—has surely reinforced for an ever-more-isolated Iranian regime the necessity of possessing the ultimate deterrent. It is therefore not surprising that each time Iran has entered into nuclear negotiations with the international community in the past twelve years, it has done so disingenuously in order to stall for time. This latest round is most likely no different. All the while, Tehran has continued its nuclear program. Moreover, Iran’s security environment has deteriorated significantly in recent years.

Allowing Iran’s nuclear program to continue is not an easy conclusion. The only other choice is an extreme option involving regime change. With diplomacy now the established strategy of the Obama administration, putting something stronger than economic sanctions back on the table is only something that is possible after the U.S. presidential election in November 2016. Even then, escalation is unlikely and unsavory. By all estimates, Iran would be technically able to manufacture a nuclear weapon in 2016 anyway, should it want to. A smart analysis, informed by past behavior, would be on Iran understanding this timetable and stretching talks out so that it is able to keep the proliferation option open.

The best way that the West can manage Iran is to keep containing it so the inherent staleness and corruption of the old guard either exhausts, or consumes itself. So, the P5+1 should encourage change in Iranian domestic politics by taking the nuclear issue off the table by letting it play out. Then, with nuclear politics in the rear-view mirror, the Regime will be forced to address the deep inconsistencies in how it governs its nation and its lack of rapport with the bulk of the Iranian population—who are deeply disillusioned by a political order that does not speak for them.

Stephen McGlinchey is Senior Lecturer of International Relations at the University of the West of England, Bristol and the author of US Arms Policies Towards the Shah’s Iran (Routledge, 2014). He is also Lead Editor of E-International Relations.

Image: Iran president website