U.S. Nuclear Strategy and the Future of Arms Control

Pessimism about Chinese or Russian intentions is certainly warranted, but their future capabilities for carrying out a disarming first strike are uncertain.

In addition, not all Russian and Chinese ICBMs are deployed in silos. Russia has significant numbers of ICBMs in mobile basing, and China is thought to have significant numbers of long-range missiles that are mobile and based in underground tunnels. In Russia’s case, its survivable ICBMs are supplemented by its Borei-class ballistic missile submarine force with Bulava missiles, providing an additional survivable component to its deterrent and carrying a nontrivial number of warheads.

China’s SSBN/SLBM force is inchoate and small compared to Russia’s or the United States’, but China is intent on improving its sea-based deterrent to upgrade that portion of its strategic nuclear triad. Neither China nor Russia has a strategic bomber force that matches America’s current and future forces, but bombers are not competitive with missiles as first-strike weapons. If it can survive enemy first strikes, however, the U.S. strategic bomber force can contribute significantly to post-attack strikes and deterrent missions.

Nuclear policy expert Henry Sokolski has noted that growing numbers of Chinese and Russian nuclear weapons may pose insuperable challenges to U.S. force modernization, especially with regard to damage limitation objectives in U.S. nuclear employment policy. He proposes that, instead of expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal to maintain a high level of damage limitation, policymakers should consider another approach to making an enemy first strike implausible or impossible. The alternative is an exponential growth in the number of possible aim points that China and Russia would have to target to neutralize America’s deterrent. For example, silo-based ICBMs could be transitioned to mobile basing, and alternative basing on commercial aircraft, trains, and ships should also be explored. Ultimately:

“Instead of Russia and China needing hundreds of nuclear-armed missiles and thousands of nuclear warheads to accomplish [a successful first strike], you would want to force them to require tens of thousands of warheads—and still not be confident of knocking out all of America’s nuclear force.”

From a scientific perspective, Dr. Sokolski’s proposal has appeal, but as a political proposition, it is likely to meet with strenuous objections from the U.S. strategic planning and policy communities. Intelligence estimation dealing with tens of thousands of warheads on each side would be challenging to existing capabilities for monitoring and verification of weapons deployments. Arms control would, therefore, become more complicated and possibly unmanageable in practice. Reciprocal competition in creating additional aim points for strategic weapons could expand the list of weapons and launchers demanded by Chinese, Russian, and American militaries in order to restabilize deterrence. In addition, a “successful” standoff in nullification of a comprehensive first strike could drive competition into more limited first strike opportunities against selected targets among U.S. allies in Europe and Asia. Another likely outcome, if comprehensive attacks via heavy metal are precluded, is that states will look in other directions for strategic surprise: strikes against space-based assets for warning, attack assessment, reconnaissance, communications, and geolocation, as well as attacks on cyber defenses.

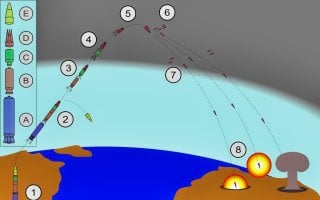

As opposed to simply upgrading warheads or deploying newer generations of launchers, the major nuclear powers might seek tacit or explicit arrangements to limit the “bonus” from nuclear first strike as a last resort, i.e., preemption, relative to riding out the attack and retaliating. Hypersonic weapons pose a particular problem in this regard. Hypersonics threaten to reduce the amount of time available for warning, attack characterization, and response to any nuclear first strike. In addition, some hypersonics can be equipped with evasive countermeasures to ballistic missile and air defenses. The proliferation of nuclear-armed hypersonic glide weapons or hypersonic cruise missiles would create additional pressures for automation of the nuclear response process by artificial intelligence or other digital decision aids. Faced with the possibility of imminent threats involving little or no warning time, decision-makers could be tempted to prioritize preventive instead of preemptive first strikes under crisis conditions.

Planning for the Future(s)

China’s nuclear rise is a matter of imminent concern to U.S. political leaders and their military advisors, and China’s ambitions to become a global nuclear superpower merit close attention. On the other hand, China’s nuclear modernization ambitions are not necessarily inconsistent with nuclear strategic stability and the control of future arms races. China has options among alternative nuclear futures, and even under its currently projected levels of deployment (1,000 weapons on international launchers by 2030 and 1,500 weapons by 2035), China would remain within the envelope of strategic nuclear weapons deployed by the U.S. and Russia under existing New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) protocols. U.S. planners are understandably concerned about the possibility of combined Sino-Russian nuclear attacks or coercive diplomacy. Still, Chinese and Russian interests do not always line up on the use or threat of nuclear weapons. Moreover, neither U.S. nuclear warhead modernization nor Chinese nuclear expansion can create a first-strike capability that can prevent unacceptable and historically unprecedented retaliation against the attacker or attackers. Nuclear employment policy matters insofar as it reinforces deterrence; otherwise, it is the pursuit of dead ends.

Stephen Cimbala is a Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Penn State Brandywine and the author of numerous books and articles on international security issues.

Lawrence Korb, a retired Navy Captain, has held national security positions at several think tanks and served in the Pentagon in the Reagan administration.

Image Credit: Creative Commons/Wikipedia.