Will Congress Finally Repeal the 2002 AUMF?

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 has been stretched far beyond its original reach—and it is still on the books.

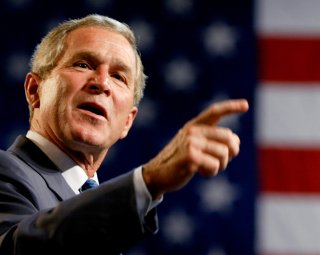

Twenty years ago this week, President George W. Bush signed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution into law, empowering his office to “defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.”

Nine years later, a 2011 military ceremony in Baghdad marked the end of the nearly decade-long invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Eleven years after that, the law has been stretched far beyond its original reach—and it is still on the books.

The story of why the 2002 AUMF remains in place today is partly one of inertia.

Despite efforts to repeal the law, Congress has so far continued to defer to the executive branch when it comes to questions of war. “It’s something that a lot in Congress recognize that they maybe should do when you talk to different offices,” says Eric Eikenberry, the government relations director at the progressive advocacy group Win Without War. “But it doesn’t seem as pressing as another issue.”

Members of Congress themselves agree that the body’s lack of initiative is a primary culprit. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA), one of the senators leading the push to repeal, recently told the Washington Post that the law is still in place “because Congress hasn’t had the backbone to lift it off the books.”

Even when Congress has tried to act, they have been unsuccessful. Twice since the war in Iraq ended, first in 2011, and then in 2019, Congress appeared close. But successive presidential administrations, and their respective Defense Departments, managed to shut those efforts down.

Today, it appears as if bipartisan groups of legislators and advocates on both the Right and Left are ready to finally bring that long race across the finish line.

Heather Brandon-Smith, the legislative director for militarism and human rights at the Friends Committee on National Legislation, told the National Interest that AUMF repeal has earned support from a variety of U.S. stakeholders, both in and outside of Congress. Whether it be conservatives who believe in Congress’ constitutional right to declare war, progressives who want to see an end to endless wars, or veterans’ groups, all of these parties have been important voices in the push for repeal in recent years.

Though the Iraq War ended more than a decade ago, the 2002 AUMF continues to play a role in national security decision-making. “The way the executive branch has interpreted the 2002 AUMF is so far beyond what Congress originally intended and what it is the text of the law itself,” says Brandon-Smith. “So, it basically leaves the president with this tool to try and use to justify military action that Congress never authorized.” The Obama administration used the law as an “alternative statutory basis” for its 2014 military effort against ISIS, even as it simultaneously continued to support the law’s repeal. The Trump administration also cited the 2002 law to help justify both the continued use of force against ISIS in Iraq and the January 2020 assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in Iraq.

But since the conclusion of the Iraq War, the 2002 AUMF has never been the primary legal justification for any of the United States’ military operations, many of which rely on the more expansive 2001 AUMF. So, the law is not only ripe for abuse, but also not needed for, or relevant to, the United States’ national security.

The 2020 killing of Soleimani proved to be something of a flashpoint for the repeal effort. The assassination of the Iranian general demonstrated how a law passed to permit one war twenty years earlier could still drag the United States into a dangerous conflict years later. “It wasn’t just that the United States killed a general from another country in Iraq, it also almost resulted in a conflict,” says Eikenberry. Had Iranian retaliation gone slightly differently, Eikenberry told the National Interest, the United States “would have been thrown into a situation with an extremely ugly escalation that Congress and civil society in the United States would have had trouble corralling.”

In theory, the legislature should want to repeal this twenty-year-old law. As Reid Smith, director of foreign policy at Stand Together, recently wrote in The American Conservative, “Repeal of the 2002 AUMF would represent a modest but nonetheless historic step toward congressional reclamation of its constitutional prerogative to initiate, oversee, and ultimately end foreign conflicts.” But Congress has consistently deferred to the executive by not repealing the authorization for the last ten years, demonstrating that foreign policy in general, and the reclaiming of war-making powers in particular, is not always a priority, even if indications today are that many members in both chambers support a repeal.

But positive momentum is accumulating, and advocates say that now is the ideal time to finally get the job done. Repeal would be both a meaningful way to reaffirm Congress’ role and as a check on a president’s potential impulse to abuse the power given to the office.

“That threat of future misuse is still very much there and is very much a reason why we, as Win Without War, are pushing for its repeal,” says Eikenberry. The Biden administration has signaled its support for repeal, so unlike his two predecessors, the president is likely to sign such a bill if it arrives at his desk. The June 2021 statement of administration policy that officially supported repeal also may have sent an important interagency signal to other departments to not stand in the way if Congress votes to repeal. And since more Democrats have generally supported repeal than Republicans, it may be vital to vote on the AUMF before the new Congress arrives in 2023, or a new president potentially takes office in 2025.

In the shorter term, the repeal of the AUMF permits Congress to reclaim a constitutional duty. “When you take away Congress’ ability to do their job based on what the Constitution requires, you’re really fundamentally acting in an undemocratic fashion,” Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), the only member of Congress to vote against both the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs, and a leading advocate for repeal, told Responsible Statecraft in a recent interview.

Some obstacles remain. Aside from the possible lack of prioritization mentioned earlier, not every member of Congress is on board with reclaiming war powers. “There are still plenty of members of Congress who want the president to have as much warmaking authority as possible,” explains Eikenberry, either to avoid having to make difficult decisions, or to ease the legal justification for a future war of choice in the Middle East.

But there appears to be wind in the sails of those who want to repeal the 2002 AUMF. Behind the leadership of members of Congress from both parties, the steady effort by activists of various ideologies, the support of the White House, and the symbolic importance of the twentieth anniversary, there is optimism that repeal could happen soon. “This is the time to make this happen,” says Brandon-Smith. “It’s really a no-brainer.”

Blaise Malley is an Associate Editor and writer at the National Interest. His work has appeared in The American Prospect, The American Conservative, Responsible Statecraft, and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter @blaise_malley.

Image: Reuters.