Will the Syria Ceasefire Last?

The battle of Aleppo, as Russia and Iran saw it, was meant to strengthen Assad's hand, not to indulge his fantasies about follow-on victories to retake the rest of Syria.

While there are no precise numbers, the carnage in Syria may have consumed as many as 470 thousand lives and forced some 4.8 million Syrians to flee, mainly to Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. So the news that the Ba’athist government of Bashar al-Assad (backed by Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah) and the High Negotiations Committee, which encompasses an array of thirty or so armed opposition groups—though not all—had agreed to a ceasefire, to take effect as of midnight on Thursday, comes as welcome news. Even those who have followed the Syrian war closely and therefore have good reasons to doubt that the latest deal to silence the guns will fare any better than did its forerunners will concede that it beats the alternative: continued bloodletting.

Yet this much is clear. Assad’s intermittent boasts that he will retake all of Syria are delusional. His army cannot possibly achieve that objective. And Iran and Russia, without whose help—on the ground (Iran) and from the air (Russia)—the Syrian army would never have prevailed in the horrific battle for eastern Aleppo, have no intention of indulging Assad’s dream. To do so would entrap them in Syria indefinitely—the anti-Assad force are down but not out. Various Islamist resistance groups remain ensconced in parts of the country, aside from Idlib. The Kurdish Protection Units (YPJ), the fighting arm of Syria’s Kurds, has carved out a statelet (“Rojava”) to the north. These redoubts would have to be taken by force. They would be doggedly defended.

After Aleppo’s bomb-battered east was finally overrun by Syrian forces this month, with help from various militias, Hezbollah fighters and Russian warplanes, the armed opposition was forced to accept defeat. As its fighters started departing in government-supplied buses, there was talk that Assad would next set his sights on Idlib province to the west, which the resistance largely controls. Idlib remains an important strategic prize, not least because it overlooks, from the north, the Alawite bastion on Syria’s coast. This stronghold stretches from areas north of Latakia toward the Turkish border and from Tartus southward toward Lebanon. In the east it is framed by the an-Nusayriyah mountain range. A resistance-controlled Idlib still presents a serious threat to the Alawites’ historic homeland. Moreover, many of the fighters who have been forced out of areas they once held, including eastern Aleppo, have moved there.

But Assad did not wheel toward Idlib after his Aleppo victory. In part that was because his army (which has shrunk to about half of its nominal size on account of deaths and desertions) and the constellation of private militias that fight alongside it were weary and overstretched. More importantly, Assad couldn’t have opened another front and plunged into another big battle without being assured of backing from Russia and Iran.

The Russians and Iranians have certainly been determined to prevent the Syrian state’s collapse, fearing that the result would be the triumph of the radical Islamist opposition groups, which have long had the most firepower and fighters and control the most territory. Moscow and Tehran are betting that these groups, once they realize that military victory is unattainable, will agree to peace talks. No one, including the Russians and the Iranians, knows what sort of Syria will emerge from such negotiations. But Moscow and Tehran want Assad’s dealmakers to sit at the bargaining table in a strong position. That, however, doesn’t require that Assad first control Syria in its entirety.

The battle of Aleppo, as Russia and Iran saw it, was meant to strengthen Assad’s hand, not to indulge his fantasies about follow-on victories to retake the rest of Syria. As Moscow and Iran see it, the Syrian state now controls all of Aleppo (Syria’s largest city) and a land corridor, which, while pockmarked by rebel-held territories, runs from Aleppo through Damascus, skirts Lebanon and approaches Jordan. These territories contain Syria’s largest urban centers and about 60 percent of its population—perhaps more, following the retaking of eastern Aleppo.

The convergent interests of Russia and Iran, Assad’s indispensable allies, produced this latest ceasefire. Important as well has been the rapprochement between Russia and Turkey and Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan’s reassessment of his Assad-must-go precondition for peace. Erdogan reconsidered his approach to Syria for three reasons. The change in Assad’s military fortunes following the Russian intervention was one. A second was the deterioration in Turkey’s relationship with the West, especially following the July 2016 coup attempt. The third was the rise on his southern flank of a Syrian Kurdish proto-state led by the People’s Democratic Union Party (PYD). The Turkish authorities see the PYD as an ally of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), which has led a decades-long insurgency in Turkey’s southeastern Kurdish-populated southeast.

All of this would suggest that the conditions for a durable ceasefire are in place and that negotiations between Assad and his opponents, scheduled to commence in Kazakhstan within a month, will be held. If you’re given to betting, don’t stake a large sum on this outcome, desirable though it may be.

Islamic State, which, despite having suffered serious losses still holds swathes of terrain in Syria north, west, center and east, isn’t party to this latest ceasefire agreement. Neither is the PYD, whose YPJ soldiers are battled-hardened and determined to preserve their gains, which neither Turkey nor Assad are likely to find acceptable if that means the consolidation of a Kurdish state. Major Islamist resistance forces—such as Harakat Ahrar al-Sham, Jaysh al-Islam, Jaysh al-Mujahedeen and others—have signed the ceasefire deal. But Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, which changed its name this summer from Jabhat al-Nusra in an apparent attempt to demonstrate its separation from Al-Qaeda, has not. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies have been the main supporters of Assad’s most powerful foes. They won’t embrace what they will doubtless see as road to peace being paved with substantial Iranian involvement. As long as they are prepared to provide their protégés money and weapons, the latter will always retain the choice of returning to the battlefield if the best terms they can get at the bargaining table aren’t good enough from their standpoint. And of course a rupture of the ceasefire could lead to tit-for-tat attacks, mutual recriminations and renewed fighting, the past becoming prologue.

Vladimir Putin may be hoping to have a ceasefire in place and negotiations underway that look promising enough before Inauguration Day so that he can present Russia to Donald Trump as a key ally in the battle against Islamic State, which the incoming president considers the principal threat in the Middle East. If that is indeed Putin's goal, he has many hurdles to clear.

Rajan Menon is Anne and Bernard Spitzer of International Relations at the Powell School, City College of New York/City University of New York. He is a senior research fellow in the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University. He is the author, most recently, of The Conceit of Humanitarian Intervention (Oxford University Press, 2016).

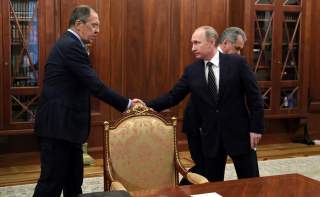

Image: Vladimir Putin and Sergei Lavrov/Kremlin