World War II Is Still 'Raging' in Asia. Can Putin and Abe End It?

Economic diplomacy may hold the key.

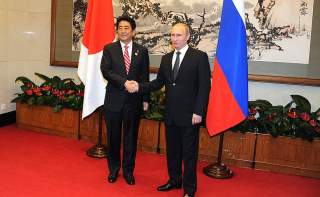

On December 15, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Russian President Vladimir Putin will try to end World War II. For over seven decades, a dispute over four islands, which Russia calls the Southern Kurils and Japan calls the Northern Territories, has prevented a formal peace agreement.

New research underscores their herculean task. A team of political scientists at the University of North Texas examined every territorial dispute involving two or more states between 1816 and 2001. To estimate the importance of territory to competitors, researchers evaluated the presence of valuable resources, ethnic ties and other factors. Japan and Russia’s island row received the highest score possible.

The historical record for resolving these “perfect storm” disputes is sobering. Current quarrels include the Golan Heights, Kashmir, and Taiwan, among others. Of those disputes that have been resolved, one third have ended through violence.

Only twice did bilateral negotiations peacefully and permanently calm a perfect storm. Both cases involve Poland, which settled border disputes with Czechoslovakia and West Germany in 1957 and 1972, respectively. Beyond looking west for inspiration, what might Abe and Putin learn from these outliers?

While each case is unique, both suggest economic diplomacy is critical for laying the groundwork for peace. Deployed correctly, trade, investment and other economic incentives can build trust, overcome ancient animosities and create an environment for winning seemingly impossible political concessions.

In the first case, a decade of economic cooperation helped Czechoslovakia and Poland settle a dispute as old as the countries themselves. Relations began to thaw after a treaty paved the way for joint development of industrial areas. Each brought something to the table, with Czechoslovakia specializing in engineering and Poland specializing in raw materials production.

Building on this foundation, targeted economic commitments increased trust and set the stage for a political deal. Key among them were Czechoslovakia’s significant investments in Polish mining. Economic conditions within Poland, which was facing a number of headwinds and needed access to capital, made these incentives even more attractive.

In the second case, it was a trade agreement that paved the way for a peaceful resolution between Poland and West Germany. Months before resolving their border dispute, the two countries clinched a deal that provided Poland with significant market access. Over the next four years, Poland’s exports to West Germany grew nearly six fold.

Despite a condensed timeline, the overall pattern is similar: economic diplomacy made political progress possible. In early 1970, Poland’s minister for foreign trade became the first official of post-war Poland to visit West Germany. Six months later, West Germany’s economic minister became the first cabinet-level official to visit post-war Poland. In December of that year, the border dispute was resolved.

These cases prove that even the thorniest disputes can be resolved peacefully, but also suggest that Japan and Russia have more work to do.

To be sure, economic relations between Japan and Russia have been improving, with trade quadrupling over the last decade. Furthermore, Abe firmly grasps the importance of economic diplomacy. In September, he added a new post for economic cooperation with Russia to the portfolio of Japan’s minister for economy, trade and industry.

But the question is whether cooperation in the economic realm has reached a tipping point that could catalyze progress in the political realm. Looking closer, there is plenty of room for increased cooperation. That could include greater investment from Japan in Russia’s Far East, especially infrastructure projects, as well as joint development of the islands.

Another challenge, of course, is that economic diplomacy does not operate in a vacuum. Just as Poland was eager for greater trade and investment, Russia’s sclerotic economy is primed for Japan’s economic incentives. But China’s rise has increased the strategic value of the islands, where Russia has been developing military installations. This could raise the bar for economic cooperation.

It would be a mistake to judge this month’s summit solely on whether a grand bargain is reached. Given the perfect storm that Abe and Putin confront, a better gauge of success is whether they can continue building a foundation for peace. Successful steps forward could take many forms, but history suggests the most important would be economic.

Jonathan Hillman is Director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Image: Vladimir Putin with Shinzo Abe in 2014. Kremlin.ru