The Case for Basic Income In a Time of the Coronavirus

The UK needs to embrace a basic income for all, independent of labour market status, to make sure that these people feel secure enough to stay at home to avoid spreading the illness.

The outbreak of coronavirus has exposed the fragility of a labour market characterised by the growing gig economy, zero-hours contracts and self-employment. None of these forms of work have employment benefits like sick pay. These workers are being hung out to dry with little choice but to try and work, even in the middle of a pandemic.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced major wage-subsidy measures from the government with 80% of business’ wage bills – up to £2,500 per month per worker – being paid by the state. This is a huge concession and one to be commended.

But more needs to be done for gig workers and others who are classed as self-employed (about one-fifth of the workforce). They are excluded from this offer and will only be able to claim Universal Credit, which is £94.25 per week. And to this we must add carers in the home, who are excluded from any form of recompense for their labours.

Read more: Coronavirus: rationing based on health, equity and decency now needed – food system expert

The UK needs to embrace a basic income for all, independent of labour market status, to make sure that these people feel secure enough to stay at home to avoid spreading the illness. The concept of a “universal basic income” is hardly new – it has been discussed in academic circles for many years. Some consider the concept to date as far back as Thomas More’s Utopia in 1516.

Now some MPs are calling for a universal basic income to help deal with the crisis, and the Independent Workers of Great Britain union is taking legal action against the government to extend the wage guarantee to gig workers. But due to the different ways that the left and right view the economy, these calls are likely to fall on deaf ears.

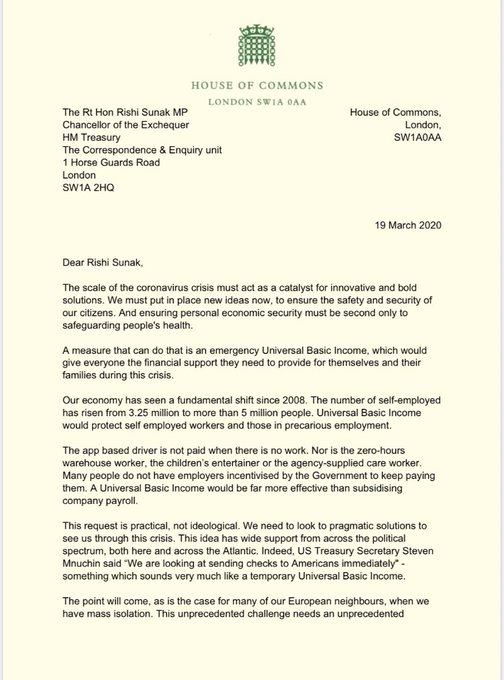

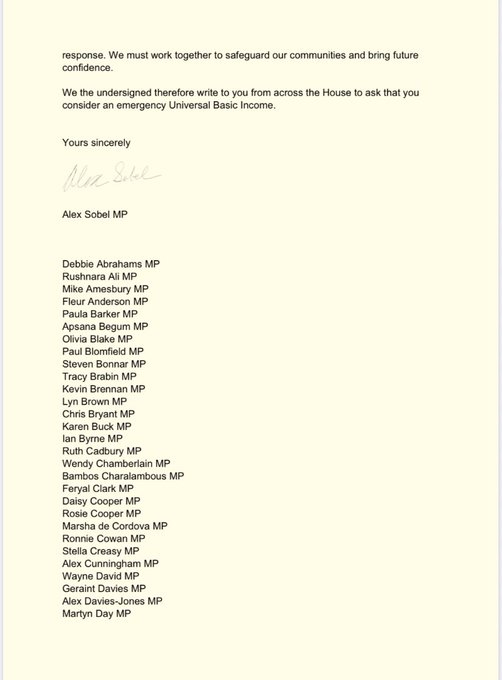

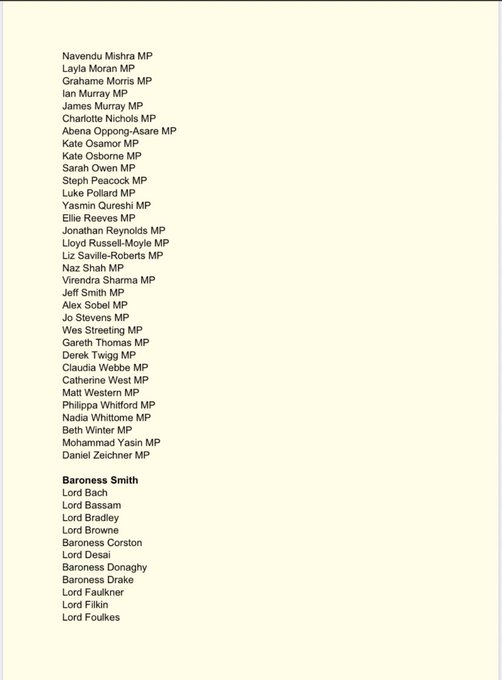

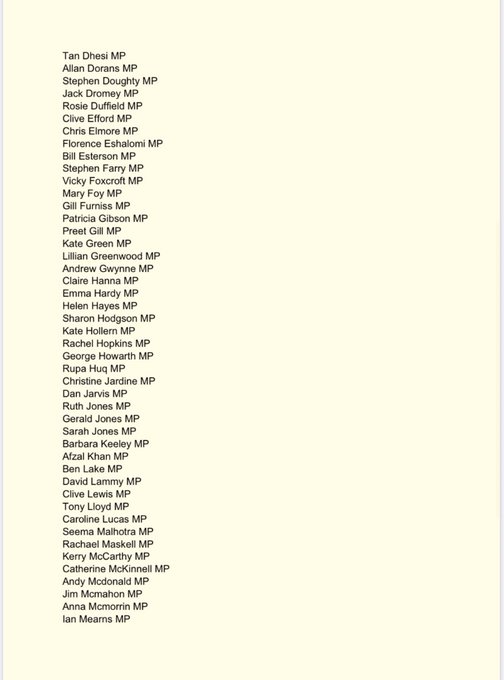

I have joined 150 MPs across different parties in writing to @RishiSunak calling for an emergency Universal Basic Income.

At this time, direct payments are the only way to guarantee real financial security to workers in Poplar and Limehouse and beyond. #Covid_19

The notion of a basic income is taken seriously at the heart of modern economics. Studies have shown that, if set appropriately, a universal basic income can achieve the same redistributive impact as another concept sometimes mooted by economists, a negative income tax.

A negative income tax ensures that those who earn below a certain threshold receive money from the government instead of paying it. To give an example, if the threshold were set at £10,000 and the negative income tax rate were 20% then an individual earning £5,000 would receive £1,000 from the government (to give them a net salary of £6,000). For anyone earning over £10,000 the first £10,000 of their earnings would be treated as free from income tax (just like the personal allowance functions in the UK).

What would it cost?

The great challenge for either approach is in their overall fiscal cost and the amount of tax all those above the threshold would have pay. To take an example, there are almost 54 million people over the age of 16 in the United Kingdom. To pay each and every one of them an annual total of £10,000 would entail a cost of £540 billion per annum. Even given the removal of all benefits (including the state pension), the fiscal costs would be substantial. To match the minimum wage – approaching £16,000 per annum – would be prohibitive.

As a result, an alternative idea of a “jobs guarantee” has garnered academic attention and some public support. Under this scenario, people would be guaranteed work by the state – although it is questionable how socially useful some of that work might be (John Maynard Keynes famously gave the example of the government paying workers to dig holes in the ground and fill them up again). A scheme like this would secure the right of people to work in an absolute sense and would mean they are not seen to be getting “something for nothing”.

But the job guarantee strategy has largely been conceived to alleviate the problem of unemployment. The challenge of the coronavirus economy is that the state is actively having to stop people from going out to work (unless you fall into the “key worker” category). But while some jobs can be largely done from home, this is not the case for a great many. As a result, society faces a very different challenge to that envisaged by advocates of a job guarantee.

A contingent basic income

We want people to keep working, but not at the cost of social contact, which could risk spreading the virus. Our idea of a “contingent basic income” is slightly different to the universal basic income, which would be paid at the same amount regardless of circumstance (or indeed, willingness to work).

We believe that a basic income should be a right, but it should be underpinned by a principle of reciprocity. So in exchange for society covering individual welfare, people must contribute to society in some way (unless they are retired, in which case an augmented state pension would substitute).

For example, the income could be conditional on workers undertaking regular training when they have spells of unemployment or underemployment. This would have the dual beneficial effect of boosting productivity and equipping workers with key skills needed to transition our economy away from fossil fuels to that of greening the economy – vital in the fight against climate change.

It would cost about £540 billion to award £10,000 a year to all those over 16. However, in practice the costs would be less as by definition a contingent basic income would be contingent on behaviour. So the spectrum of eligibility is narrower. It would exclude those who have chosen to take early retirement (who are typically wealthy) as well as students and those who choose not to work but cannot demonstrate that they are primary caregivers.

Caring for carers

Underpinning a contingent basic income must be a recognition of the importance of being a carer. The idea is that it would not entrench women in care roles but rather would serve as a prop to encourage men to take on more care work and help to ensure gender balancing.

Studies have suggested that attempts to promote a basic income need to take account of “the nature of women’s lives and work and how these should be valued”. Otherwise, a universal basic income could have damaging effects on women’s labour market participation.

As our previous research shows, the growth of gig work and self-employment in general has created a large group of people for whom not working means not eating. There is a clear imperative to ensure that “work” is posited in a wider system of regulation and benefits that aid personal and professional development for all. The COVID-19 crisis may yet stimulate such a re-pivoting of the state to enable this to happen.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alex de Ruyter is a Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Brexit Studies at the Birmingham City University.

David Hearne is a Researcher at the Centre for Brexit Studies at Birmingham City University.

Image: Reuters