Blinded by the Light: Astronomers Discover Brightest Supernova Ever Seen

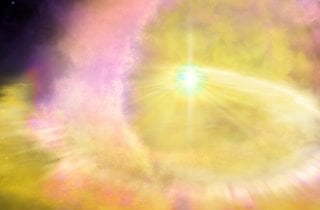

A gigantic star explosion, known as SN2016aps, now has been confirmed to be the brightest supernova ever seen, according to a new study.

A gigantic star explosion, known as SN2016aps, now has been confirmed to be the brightest supernova ever seen, according to a new study.

The supernova, which occurred in a distant galaxy about 3.6 billion light-years from Earth, is considered to be more than twice as bright as any other stellar explosion in recorded history.

“In a typical supernova, the radiation (or observable light) is less than 1 percent of the total energy,” University of Birmingham astronomer Matt Nicholl, the lead author of a paper on the discovery published in Nature Astronomy, said in a press release. “But in SN2016aps, we found the radiation was five times the explosion energy of a normal-sized supernova. This is the most light we have ever seen emitted by a supernova.”

A scientific team from Harvard University, Northwestern University, Ohio University and the University of Birmingham watched and analyzed the supernova explosion for two years via NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and other instruments on the ground, and it was able to determine that its mass was as much as 100 times that of our sun’s mass, and five to 10 times more massive than a typical observed supernova.

This particular supernova was first discovered in 2016 by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System at the Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii.

SN2016aps is considered to be so extreme that Nicholl and his colleagues believe it might be a “pulsational pair-instability” supernova, in which two large stars merged before the massive explosion. Such cosmic events that produce a “super supernova” have been only hypothesized.

“The gas we detected was mostly hydrogen – but such a massive star would usually have lost all of its hydrogen via stellar winds long before it started pulsating,” Nicholl said. “One explanation is that two slightly less massive stars of around, say 60 solar masses, had merged before the explosion. The lower-mass stars hold onto their hydrogen for longer, while their combined mass is high enough to trigger the pair instability.”

The authors of the study agreed that this discovery came at a wonderful time, in which next-generation tech advancements, such as the new $10 billion James Webb Space Telescope slated to launch next year, could be used to focus on similar mind-bending events in the future.

“Now that we know such energetic explosions occur in nature, NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope will be able to see similar events so far away that we can look back in time to the deaths of the very first stars in the universe,” Harvard Astronomy Professor Edo Berger, who co-authored the paper, said in a statement.

Ethen Kim Lieser is a Tech Editor who has held posts at Google, The Korea Herald, Lincoln Journal Star, AsianWeek and Arirang TV.