Why America’s RAH-66 Comanche Stealth Helicopter Crashed and Burned

The quest for a true stealth helicopter continues.

The U.S. has long led the world in stealth technologies, and for a time, it looked as though America’s love for all things low-observable would extend all the way into rotorcraft like the RAH-66 Comanche Helicopter.

Despite being only a decade away from ruin, the Soviet Union remained a palpable threat to the security and interests of the United States at the beginning of the 1980s. However, elements of America’s defense apparatus were beginning to look a bit long in the tooth after decades of posturing, deterrence, and the occasional proxy war.

With the Soviet Union was believed to still be funneling a great deal of money into their own advanced military projects, the U.S. Army set to work on finding a viable replacement for their fleets of Vietnam-era light attack and reconnaissance helicopters in its forward-looking Light Helicopter Experimental (LHX) program. The program’s intended aim was fairly simple despite the complexity of the effort: To field a single rotorcraft that could replace the UH-1, AH-1, OH-6, and OH-58 helicopters currently parked in Army hangars.

By the end of the decade, the Army announced that two teams, Boeing–Sikorsky and Bell–McDonnell Douglas, had met the requirements for their proposal, and they were given contracts to develop their designs further. In 1991, Boeing–Sikorsky won out over its competition and was awarded $2.8 billion to begin production on six prototype helicopters.

The need for a stealth helicopter

The Boeing–Sikorsky helicopter, dubbed the RAH-66 Comanche, was intended to serve as a reconnaissance and light attack platform. Its mission sets would include flying behind enemy lines in contested airspace to identify targets for more powerful attack helicopters or ground units, but the RAH-66 wouldn’t have to back away from a fight.

In order to meet the Army’s demands, the Comanche would need to be able to engage lightly armored targets as well as identify tougher ones for engagement from more powerful AH-64 Apaches.

Most importantly, the RAH-66 needed to be more survivable than the Army’s existing scout helicopters in highly contested airspace, which meant the new Comanche helicopter would need to borrow design elements from existing fixed-wing stealth platforms like the F-117 Nighthawk to defeat air defense systems and missiles fired from other helicopters.

The Boeing–Sikorsky team quickly set about building the program’s first two prototypes, leveraging the sort of angular radar-reflecting surfaces that gave the Nighthawk its enigmatic visual profile. Those surfaces themselves were made out of radar-absorbing composite materials to further reduce the RAH-66’s radar signature. The stealth helicopter also managed engine exhaust by funneling it through its shrouded tail section, reducing its infrared (or heat) signature to further limit detection.

Its specially designed rotor blades were canted downward to reduce the amount of noise the helicopter made in flight. Finally, a full suite of radar warning systems, electronic warfare systems, and chaff and flare dispensers would help keep the RAH-66’s crew safe while they rode behind Kevlar and graphite armor plating that could withstand direct hits from heavy machine gunfire.

The result of all this technology was a stealth helicopter said to have a radar cross-section that was 250 times smaller than the OH-58 Kiowa helicopter it would replace, along with an infrared signature reduced by a whopping 75%. It wasn’t just tough to spot on radar or hit with heat-seeking missiles either. The Comanche helicopter was also said to produce just half the noise of a traditional helicopter. While the rotorcraft could still be heard as it approached, that reduced signature would mean enemy combatants would have less time to prepare before the Comanche closed in on them.

The RAH-66 was about more than stealth

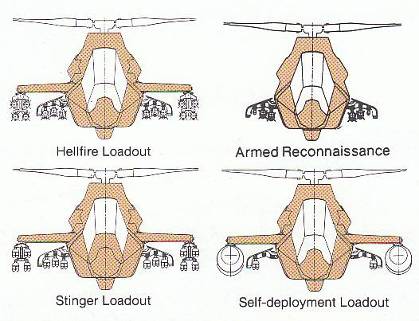

With the Comanche’s stealth technology spoken for, next came the armament. The stealth helicopter was expected to engage both ground and air targets in a combat zone, and its munitions reflected that goal. Like the stealth fighters to come, the Comanche limited its radar cross-section by carrying its weapons internally, including a retractable 20-millimeter XM301 Gatling cannon and space inside the weapons bays for six Hellfire missiles. If air superiority had been established and stealth was no longer a pressing concern, additional external pylons could carry eight more Hellfires.

However, if the Comanche was sent out to hunt for other attack and reconnaissance helicopters behind enemy lines, it could wreak havoc with 12 AIM-92 Stinger air-to-air missiles. Again, with air superiority established, an additional 16 Stinger missiles could be mounted on external pylons.

Armament options for the RAH-66 Comanche (Sikorsky Archives)

The pilot and weapons officer onboard would have utilized a combination of cockpit displays and helmet-mounted systems similar to the more advanced heads up and augmented reality displays found in today’s advanced stealth aircraft like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

It was equipped with a long-range Forward-Looking Infrared Sensor to help spot targets, as well as an optional Longbow radar that could be mounted above the rotors to allow the pilot to peak just the radar over hills or buildings–giving the crew important situational awareness of the battlefield ahead while limiting exposure of the rotorcraft itself. Once the Comanche spotted a target, a laser could be used to lock on for its onboard weapons systems.

The RAH-66 Comanche’s air-to-air credibility was further bolstered by the platform’s speed and agility. With a top speed just shy of 200 miles per hour and enough acrobatic prowess to nearly pull off loop-de-loops, the Comanche was fast, agile, and powerful… but by the time the first two Comanche prototypes were flying, it was also widely seen as unnecessary.

The U.S. has long led the world in stealth technologies, and for a time, it looked as though America’s love for all things low-observable would extend all the way into rotorcraft like the RAH-66 Comanche Helicopter.

Despite being only a decade away from ruin, the Soviet Union remained a palpable threat to the security and interests of the United States at the beginning of the 1980s. However, elements of America’s defense apparatus were beginning to look a bit long in the tooth after decades of posturing, deterrence, and the occasional proxy war.

With the Soviet Union was believed to still be funneling a great deal of money into their own advanced military projects, the U.S. Army set to work on finding a viable replacement for their fleets of Vietnam-era light attack and reconnaissance helicopters in its forward-looking Light Helicopter Experimental (LHX) program. The program’s intended aim was fairly simple despite the complexity of the effort: To field a single rotorcraft that could replace the UH-1, AH-1, OH-6, and OH-58 helicopters currently parked in Army hangars.

By the end of the decade, the Army announced that two teams, Boeing–Sikorsky and Bell–McDonnell Douglas, had met the requirements for their proposal, and they were given contracts to develop their designs further. In 1991, Boeing–Sikorsky won out over its competition and was awarded $2.8 billion to begin production on six prototype helicopters.

The need for a stealth helicopter

An RAH-66 Comanche (bottom) flying in formation with an AH-64 Apache (top). (WikiMedia Commons)

The Boeing–Sikorsky helicopter, dubbed the RAH-66 Comanche, was intended to serve as a reconnaissance and light attack platform. Its mission sets would include flying behind enemy lines in contested airspace to identify targets for more powerful attack helicopters or ground units, but the RAH-66 wouldn’t have to back away from a fight.

In order to meet the Army’s demands, the Comanche would need to be able to engage lightly armored targets as well as identify tougher ones for engagement from more powerful AH-64 Apaches.

Most importantly, the RAH-66 needed to be more survivable than the Army’s existing scout helicopters in highly contested airspace, which meant the new Comanche helicopter would need to borrow design elements from existing fixed-wing stealth platforms like the F-117 Nighthawk to defeat air defense systems and missiles fired from other helicopters.

The Boeing–Sikorsky team quickly set about building the program’s first two prototypes, leveraging the sort of angular radar-reflecting surfaces that gave the Nighthawk its enigmatic visual profile. Those surfaces themselves were made out of radar-absorbing composite materials to further reduce the RAH-66’s radar signature. The stealth helicopter also managed engine exhaust by funneling it through its shrouded tail section, reducing its infrared (or heat) signature to further limit detection.

Its specially designed rotor blades were canted downward to reduce the amount of noise the helicopter made in flight. Finally, a full suite of radar warning systems, electronic warfare systems, and chaff and flare dispensers would help keep the RAH-66’s crew safe while they rode behind Kevlar and graphite armor plating that could withstand direct hits from heavy machine gunfire.

The result of all this technology was a stealth helicopter said to have a radar cross-section that was 250 times smaller than the OH-58 Kiowa helicopter it would replace, along with an infrared signature reduced by a whopping 75%. It wasn’t just tough to spot on radar or hit with heat-seeking missiles either. The Comanche helicopter was also said to produce just half the noise of a traditional helicopter. While the rotorcraft could still be heard as it approached, that reduced signature would mean enemy combatants would have less time to prepare before the Comanche closed in on them.