Diplomatically Insulting the Chinese

The White House greets the Chinese with condescending lectures and thinly veiled threats. And somehow still makes progress.

The conventional wisdom is that these events mark a dramatic improvement in a relationship that has been marked by growing tensions in recent years. That interpretation is partially correct, but there are some worrisome countercurrents that are also important. Despite the improving communication between the two sides, U.S.-China relations remain strained, and there are troublesome issues that will not be easy to ameliorate, much less resolve.

The opening day of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue illustrated both positive and negative trends. On the positive side, the Chinese delegation for the first time included high-level officers of the PLA. Their absence from those meetings in previous years left a noticeable void in the discussions, especially on such crucial issues as nuclear weapons policy and the military uses of space. American officials also viewed the lack of a military contingent in the Chinese delegation as tangible evidence of the PLA’s continuing wariness, if not outright hostility, toward the United States. The presence of those leaders in the latest dialogue was an indication that the cold war that had developed between the PLA and the Pentagon since the collision between a U.S. spy plane and a Chinese jet fighter in 2001 was finally beginning to thaw.

On the other hand, the opening remarks of Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and other U.S. officials struck a confrontational tone. They expressed sharp criticism of Beijing’s recent arrests of activists and artists following the pro-democracy uprisings in the Middle East. More broadly, Clinton stated that “We have made very clear, publicly and privately, our concern about human rights.” In an interview in The Atlantic, released during the talks, Clinton was even more caustic, accusing China’s leaders of trying “to stop history,” which she described as “a fool’s errand.”

It was not surprising that the U.S. delegation would raise the human rights issue in the course of the dialogue. But it was not the most constructive and astute diplomacy to highlight during the opening session perhaps the most contentious topic on the agenda. A senior administration official later stated that the discussions on human rights were “very candid,” which was probably an understatement.

The broader context of the opening session was not overly friendly either. While that session was taking place, President Obama conducted a lengthy telephone conversation with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The White House issued a bland statement that the two leaders discussed matters of bilateral and international concern, including the killing of Osama Bin Laden, but the underlying message to the Chinese was anything but subtle. The timing especially sent a signal to PRC leaders that in addition to Washington’s strategic links with its traditional allies in China’s neighborhood (especially Japan), the United States had key options available regarding the other rising regional giant—and Chinese strategic competitor—India. As in the case of the lectures on human rights, highlighting U.S.-India ties at that moment did not help ease bilateral tensions with Beijing.

Even when U.S. officials ostensibly sought to be conciliatory, the attempt often came across as self-serving and borderline condescending. Secretary of the Treasury Tim Geithner, for example, praised some “very promising changes” in Beijing’s economic policy that had taken place during the previous year, especially on the currency valuation issue. But there were few offers of economic carrots from the U.S. side. The emphasis was always on the concessions Washington expected from Beijing.

The closed-door meetings appeared to be more constructive than the public session, as the participants reached agreement on a number of measures, both minor and significant. In the former category was the announcement of Beijing’s decision to offer twenty thousand scholarships to American students for study in China. In the latter category was a two-pronged agreement, which included both a commitment to conduct regular talks (dubbed “Strategic Security Dialogues”) regarding security problems in East Asia and a “framework for economic cooperation” to address the full range of occasionally contentious bilateral economic and financial issues. In addition, Beijing made commitments to increase the transparency of China’s economy, especially the government’s use of export credits.

Progress on security and economic topics was gratifying and holds considerable potential. But whether the outcome deserves the label “milestone agreement,” as officials contended, remains to be seen. The significance of the accord depends heavily on the subsequent execution, especially on the Chinese side. Nevertheless, the dialogue clearly ended on a high note, and one that was better than anticipated following the U.S. delegation’s brusque comments at the opening session.

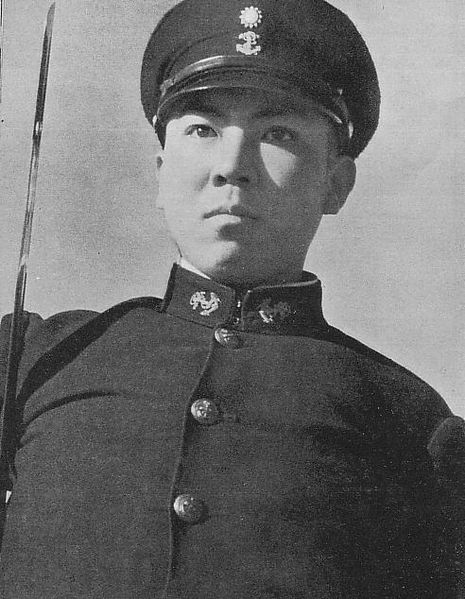

Expectations regarding the visit of General Chen and his PLA colleagues are also upbeat. The visit itself is a significant breakthrough. Military-to-military relations have been tense and episodic for years. The most recent disruption occurred in early 2010 when Beijing angrily severed those ties following the Obama administration’s announcement of a multi-billion-dollar arms sale to Taiwan.

Despite the cordial rhetoric accompanying this trip (and the full military honors accorded Chen during a ceremony at Fort Myer), the visit has far more symbolic than substantive importance. The U.S. and Chinese militaries are not about to become best friends. The best that can realistically be expected would be measures to improve communications between forces deployed in the air and on the sea in the Western Pacific region to reduce the danger of accidents or miscalculations. Any breakthrough on larger strategic disagreements will have to be reached between officials at higher pay grades than even General Chen and his American counterparts.

The change in tone in the U.S.-China relationship is welcome, since better cooperation on both economic and strategic issues is important. Trends on both fronts over the past several years have been worrisome. A failure to cooperate on economic matters not only jeopardizes both the U.S. and Chinese economies, it also poses a threat to the global economic recovery. Animosity on security topics creates dangerous tensions in East Asia and undermines progress on such issues as preventing nuclear proliferation.

Nevertheless, while China and the United States have significant interests in common, they also have some clashing concerns in both the economic and strategic arenas. There are bound to be tensions between the United States, the incumbent global economic leader and strategic hegemon, and China, the rapidly rising economic and military power. The critical task for leaders in both countries is to manage those tensions and to keep them under control.

The political and diplomatic dance between such great powers is inevitably a wary, delicate one. But the alternative would be the kind of outright hostility that marked the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, and that would be to no one’s benefit.