Lessons from the Melian Dialogue: A Case Against Providing Military Support for Ukraine

As the war in Ukraine rages on, and peace talks have yet to commence, it’s long past time we ask ourselves if helping Kyiv regain control of eastern Ukraine is worth the risks, and if there isn’t another way forward.

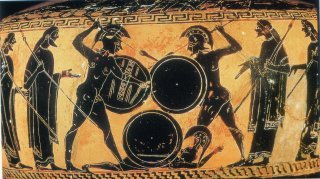

The Melian Dialogue is among the most heavily analyzed sections in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. Athens wanted to take Melos, a small island, as a subject of their empire. The Athenians sent envoys to negotiate with the Melians, who had no true means of resisting a superpower like Athens unless their allies, the Spartans, chose to once again fight a long, bloody war on their behalf.

Unlike Melos, which never received Spartan aid and whose population was ultimately annihilated, Ukraine has received an endless supply of military aid from Western countries. Russian leaders regularly warn that the West’s military support of Ukraine could lead to a full-fledged war between NATO and Russia. After all, the truth of the matter is that American and other NATO members’ weapons are being sent to Ukraine in order to kill Russian soldiers.

Furthermore, while the Melian Dialogue certainly consisted of a lot of talking, there was hardly any true negotiation. Each party maintained unconditional positions that were paradoxical to one another, making any meaningful progress impossible. The same can be said with Russia and Ukraine; each party refuses to even come to the negotiating table until the other agrees to unacceptable demands. To avoid a Melian ending in Ukraine, one or both parties will have to modify their conditions. To avoid a worse ending, NATO should consider the following questions. Was it prudent for Sparta not to intervene in Melos, or should they have risked another massive war with Athens over the island? Should Melos have surrendered? As the war in Ukraine rages on, and peace talks have yet to commence, it’s long past time we ask ourselves if helping Kyiv regain control of eastern Ukraine is worth the risks, and if there isn’t another way forward.

The Athenian envoys opened the dialogue by acknowledging that they were brought only before the rulers of Melos, or “the Few,” because the people,“the Many,” would quickly agree to the Athenians’ demands and inferred that the Few knew this to be true. The Melians stated that though they would take part in a dialogue, there was hardly any serious discussion to be had. They understood that the Athenians had made up their minds and intended to turn Melos into their subject, which the Melians refused to consider. Herein lies the key problem that persists throughout the entire dialogue: each side maintained unconditional positions that were paradoxical to one another. The unconditional Athenian position was that Melos would become a subject of the Athenian empire, the only question being whether they would secure it through Melian submission or war. The unconditional Melian position was that they would not become a subject of the Athenian empire, the only question being whether they would achieve that through persuasion or war. The only outcome that both parties were willing to accept was also the one they both wanted to avoid. Does this sound familiar?

Kyiv has offered a ten-point peace proposal to the Russians, which includes the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine and the restoration of pre-war borders. It should come as no surprise that Russia declined Kyiv’s proposal. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov has urged Ukraine to accept the “new realities” and that if they don’t, “no kind of progress is possible.” Among these “new realities” include the annexed regions of eastern Ukraine being part of the Russian Federation. Referendums were held in each of these regions, and though they all allegedly voted to join the Russian Federation, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, along with most of the Western world, has denounced these referendums as “shams” with “no legal value.”

Like the Athenians and Melians, Russia and Ukraine each maintain paradoxical, unconditional positions. The party being aggressed has every right to resist. That said, if either of these countries eventually become serious about ending the war for the sake of preventing further loss of life and destruction, there will have to be peace talks, and concessions will have to be made. Short of that, the only alternative is for one side to military defeat the other, which would lead to a far worse outcome for the loser.

The Athenians, like the Russians today, encouraged the Melians to accept the reality before them. They dismissed all arguments grounded in the abstract, such as the importance of hope. The Melians spoke of “the fortune of war” and stated that “to submit is to give ourselves over to despair, while action still preserves for us a hope that we may stand erect.” The Athenians responded coldly, referring to hope as “danger’s comforter,” and said that when reality is too harsh to accept, people “turn to the invisible, to prophecies and oracles, and other such inventions that delude men with hopes to their destruction.” Ukraine is in a similar position, but unlike the Melians, they have been fed reasons to be hopeful by Western governments. Melos received no support from their allies, whereas Ukraine has received foreign military aid since the beginning of the war. This has been noticeably beneficial to the Ukrainians. As of November 2022, Ukraine has reclaimed over 50 of percent the land captured by Russia, though Russian forces still control roughly 15 to 20 percent of the country. Even with most NATO members agreeing to supply Ukraine with tanks, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy has stated that dozens of tanks will hardly make a difference, given the fact that Russia has thousands of them. Despite the quantity being insufficient, those tanks do provide a real benefit to the Ukrainian military, according to Zelenskyy. “They do only one very important thing—they motivate our soldiers to fight for their own values. Because they show that the whole world is with you.” In short, the West has supplied Ukrainians with hope.

The Melians cited the prospect of a Spartan intervention as a stronger argument against Athenian aggression. They claimed that the Spartans would intervene, “if only for very shame…”. Again, the Athenians struck them down, saying that danger is something “the Spartans generally court as little as possible.” One might not think of the United States as a nation that courts danger infrequently, given their long history of foreign interventions. But in the post-World War II era, the United States has exclusively fought against relatively minor powers. Major powers, which make up most of the United States’ greatest adversaries, tend to be off limits, and rightfully so. Not because America would lose a conventional war against a major power, but because of one key factor: nuclear weapons. In this regard, Americans are like the Spartans, who generally court danger as little as possible.

After going back and forth several more times over the prospect of a Spartan intervention, the Athenians suggested that the Few should seek advice from others before it’s too late. Before leaving, they told the Melians to make their final decision carefully, as it was a choice between “prosperity or ruin.”

The Few never changed their minds, they never sought advice from others and war ensued. The Melians held out for roughly a year before finally surrendering, at which point every man in Melos was executed, the women and children were sold into slavery, and Athenian colonists settled Melos for themselves. The Many were annihilated because of a decision made by a small group of individuals. To prefer death over the loss of sovereignty is noble. Subjecting an entire city to that decision is probably poor governance. If the Many had any say in this dialogue, would they have made the same decision, or would they have preferred to live as subjects of the Athenian empire? For the war in Ukraine to end through peace talks instead of a more Melian fate, either Russia or Ukraine will have to change their unconditional demands.

There are only two possible outcomes for Ukraine. Either most of Ukraine will remain under Kyiv’s control, or all of Ukraine will be reduced to rubble, its leadership overthrown, and the entire country will potentially face annexation. The first outcome relies on peace talks taking place before the Ukrainian military is outright defeated. Those peace talks would probably include Kyiv surrendering its eastern territory to Russia. The second outcome is virtually guaranteed if Ukraine is defeated before agreeing to a peace treaty that involves forfeiting territory it hasn’t had real control of since 2014 anyway. This is true even with a continued supply of Western military equipment.

Readers will note that excluded from these two options is the outcome that most hope for: Ukraine defeating the Russian military and regaining control of the entire country. Those in the West who promote this outcome are feeding Ukrainians with what we know to be “danger’s comforter.” The longer the West provides Ukraine with military aid, the longer Ukrainians will be deluded in the face of greater dangers than those they already face.

Ending the war through a peace treaty, even an unideal one, is an objectively better outcome than the logical conclusion of its current course. Each new round of military equipment sent to Ukraine is more advanced than the last. The first batch of American aid included anti-armor and antiaircraft munitions. Roughly a year later, NATO countries have provided Ukraine with Patriot missile systems and are in the process of supplying them with tanks as well. Meanwhile, the Russians are becoming increasingly angry with Western governments, cutting diplomatic ties, exiting treaties, and occasionally threatening nuclear war. Is helping Kyiv regain control over the eastern territory worth that risk? Alternatively, Western governments could instantly eliminate that risk by ceasing its military aid. That would, of course, expedite Ukraine’s inevitable defeat and hurt the pride of Western leaders. Was the pride of the Few, or their value of sovereignty, worth the lives of Melos’ populace? And is there a lesson to be learned from the Spartans’ decision not to intervene?