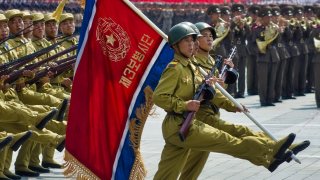

DPRK-Russia Alliance: A Win for Both, A New Era for North Korea?

A DPRK estranged from Beijing and open to new partnerships offers a space for the next administration to engage in diplomacy with Pyongyang to pacify the peninsula and counterbalance Chinese power in the region.

The June 2024 mutual defense agreement between North Korea and Russia marks the culmination of years of growing ties between Pyongyang and Moscow. The Ukraine war served as a significant accelerant in the relationship. Pyongyang provided Moscow with ammunition and weapons. In return, the Kremlin sent cash and raw materials and voted against maintaining the United Nations (UN) body monitoring sanctions on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (DPRK) nuclear program.

One should not overemphasize the role of the Ukraine war, however. The DPRK-Russia rapprochement has been years in the making. During the American unipolar moment of the 1990s and 2000s, Russia lacked the staying power to defy Washington and its allies on the North Korean nuclear program, a tertiary concern. In any case, Pyongyang had little to offer to Moscow, and the Kremlin’s pockets were too empty to assist for free.

Russia and North Korea grew closer after the 2014 Ukrainian crisis when Moscow became more confident in defying Washington. It gave up on seriously enforcing sanctions and seeking denuclearization, and high-level meetings became more frequent. The 2022 invasion of Ukraine only made Pyongyang more valuable because the Russians suddenly needed ammunition.

What Each Side Wants

For Pyongyang, Russia is the perfect partner. It is a great power capable of providing significant diplomatic, military, and economic support. But, the other way around, Moscow is too distant to threaten Pyongyang’s autonomy and sovereignty the way China can. Russia is fundamentally a European power with finite resources that cannot aspire to hegemony over the Korean Peninsula. This allows for a level of trust that is absent in the DPRK’s relations with China.

Over the long run, North Korea will gain a lot from Russia militarily, increasing its threat to South Korea and the United States. Its technological prowess will grow more rapidly than it would have otherwise. Military contacts will also lead to obtaining Russian feedback from the Ukraine war, hence increasing the Korean People’s Army’s combat readiness. Pyongyang will probably ask Moscow to share its newfound expertise in drone warfare and real-time reconnaissance-strike complex, areas where North Korea has been lagging.

For Russia, the alliance’s implications are more limited. Once the war finishes, its interest in North Korean military supplies will vanish. Despite the alliance treaty, it is hard to imagine the Kremlin committing extensive resources to the Korean Peninsula, as it will remain laser-focused on Europe for the foreseeable future. If Pyongyang were to get into serious trouble, Russian soldiers would not come and die for the DPRK’s sake.

In any case, a deep commitment would violate the essence of the Kremlin’s world strategy and its comprehension of Sino-Russian relations, where Russia is in charge of European affairs, and China takes the lead in the Indo-Pacific. Friendly Sino-Russian ties are crucial for Russian security, and Vladimir Putin cannot afford to defy China in its backyard.

How Did This Come About?

The deep causes of the DPRK-Russia alliance should also be understood in the context of Pyongyang’s recent foreign policy evolutions. In addition to the traditional rivalry with Seoul, Kim Jong-un is increasingly worried about China’s rise and its potential to establish hegemony over Korea. He naturally hopes to maintain Pyongyang’s independence and sovereignty from its gigantic, overbearing neighbor. He faces an impossible dilemma, with a formidable neighbor in the north and the stronger U.S.-South Korean alliance to the south.

Therefore, North Korea is attempting to exit the post-Cold War status quo of entrenched antagonism with Washington and Seoul and reliance on China. The failed rapprochement with Donald Trump and Moon Jae-in during the 2018 to 2019 sequence was such an attempt.

While relations with China recently reached a nadir, Pyongyang signaled an interest in engaging with Japan. It wants to diversify its partnerships to decrease Beijing’s bilateral leverage. The Russian alliance and the feelers toward the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) organization match that pattern, too.

North Korea recently abandoned its traditional goal of Korean reunification, emphasizing the separate existence of two Korean states instead. With Kim allegedly labeling China the longstanding enemy and a new American administration soon to be, the Russian alliance could signal a window of opportunity for Washington. A DPRK estranged from Beijing and open to new partnerships offers a space for the next administration to engage in diplomacy with Pyongyang to pacify the peninsula and counterbalance Chinese power in the region.

About the Author

Dylan Motin holds a Ph.D. in political science. He is currently a Non-resident Kelly Fellow at the Pacific Forum. He is also a non-resident fellow at the European Centre for North Korean Studies and a non-resident research fellow at the ROK Forum for Nuclear Strategy. He is the author of Bandwagoning in International Relations: China, Russia, and Their Neighbors (Vernon Press, 2024).

Image Credit: Creative Commons and/or Shutterstock.