The Balkans Will Pay a Heavy Price for China's Global Ambitions

Absent a common EU stance toward China, we can expect an emboldened yet fundamentally destabilizing Chinese presence in the Balkans.

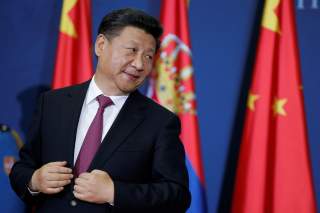

Since President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative in Kazakhstan in 2013, framing it as an overland strategy to connect Asia to Europe, China’s inroads in the Western Balkans have grown more deeply entrenched. Through bridge construction projects in Croatia, investments in Bosnia’s energy infrastructure, and a bid to develop Serbia’s 5G networks, Beijing has turned the Balkans into a critical transitway as it tries to boost the export of its manufactured goods to Europe and grease the wheels of foreign direct investment into China. Its diplomatic and economic activities in the Balkans are divorced, however, from an understanding of the complex patchwork of ethnic, political, and historical legacies that define the region—so much so that it is likely to brew instability in an already rattled region.

China’s nexus in the Western Balkans is not without precedent. In the aftermath of the Second World War and failed rapprochement between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, Mao Zedong and Josip Broz Tito emerged as the region’s “communist mavericks.” Thus, began a tumultuous relationship between China and Yugoslavia as the two jockeyed for influence in Southeastern Europe while occasionally rallying against common rivals. China remained mostly neutral amid the series of ethnic conflicts in the early 1990s—including the ethnic cleansing of Bosnian Muslims—and wars for independence that accompanied the dissolution of Yugoslavia. After the 1999 NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, however, the People’s Republic of China publicly reengaged with a $300 million infrastructure aid package. Today, China’s presence in the Western Balkans is most strongly felt in Serbia, where Beijing has established a strategic foothold.

But the close relationship China is cultivating with Serbia, coupled with its egregious human rights violations against its Muslim minority population in Xinjiang, may exacerbate regional instability amid the growing rivalry between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is particularly so as the Serb-majority entity, Republika Srpska (RS) in Bosnia is reinvigorating the Bosnian Serb secessionist movement. Since coming to power in late 2018, Bosnian President Milorad Dodik’s secessionist stance and ethno-nationalist rhetoric, including his defense of a former RS leader found guilty of committing genocide in Srebrenica, has stirred ethnic tensions.

As Serbia and Bosnian Serb political leadership align more closely with China, Beijing is holding the already tenuous stability of the region captive by empowering its most illiberal elements. China’s repression of more than a million ethnic Uighurs has largely gone without consequence; when a geopolitical heavyweight commits gross human rights violations against an ethnic minority group with impunity, it is indirectly condoning and empowering other human rights violators that receive its patronage, such as the RS secessionist movement. Unless those responsible for China’s atrocities in Xinjiang are brought to justice, an unfortunately improbable goal, its activities in the Balkans will only embolden the ethno-nationalist sentiments of RS and other Bosnian Serbs. Lest we forget, instability in the Balkans has consistently led to deadly conflicts throughout European history. While China’s growing presence in the powder keg of Europe may not directly light the first spark, it may be laying the groundwork for the next Balkans crisis.

Beijing has tried to paper over these early flickers of unrest with its monolithic narrative about the salutary effects of its Belt and Road investments—but this narrative belies the economic realities of the region. Underneath the veneer of “win-win” cooperation, Beijing is advancing its narrow economic interests at the expense of regional stability. When President Xi visited Belgrade in 2016, he proselytized to the Serbs the promise of jobs and higher standards of living that Chinese investments would bring. But in 2019, the World Bank reported that in most Western Balkan countries unemployment reached new historic lows, perhaps exacerbating the protests that have rippled through the region in recent months. Even with projects such as the Serbian steel mill Železara Smederevo, which China’s state-owned HBIS bought with an eye toward purportedly saving thousands of jobs, labor standards within the mill have taken a hit.

Finally, Beijing’s growing diplomatic and economic activism in the region has been abetted by skepticism on whether the EU can formulate a common position toward its strategies. China has built up its softer political influence in southeastern and Central Europe, both through its 16+1 format, as well as more pernicious forms of political interference through building influence networks around current and former European politicians and cozying up to influential political parties in the region. Indeed, China’s approach to Europe and its primary political body, the EU, has been one of fragmentation. It has rendered the union incapable of reaching a common view of China and thus diminishing the possibility that the EU would develop a coherent response to its strategies.

The Balkans, due to their geography, are of high strategic value to China’s near-term and long-term ambitions in Europe. Although China is engaging with many of the countries in the Balkans through the Belt and Road Initiative and other diplomatic initiatives, it has evinced a clear preference for Serbia, where illiberalism and autocratic political leadership mirrors the Chinese Communist Party’s model of governance most closely. In doing so, it is, either through lack of understanding or willful ignorance, contributing to the political alienation of Bosnia, which lies at the heart of the region’s political and ethnic tensions. Absent a common EU stance toward China, we can expect an emboldened yet fundamentally destabilizing Chinese presence in the Balkans.

Karina Barbesino is a Joseph S. Nye, Jr. research intern.

Kristine Lee is a research associate with the Asia-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security.

Image: Reuters