A Critique of Pure Gold

Mini Teaser: With Republicans eyeing a return to the gold standard, TNI presents a piece from its archives on tea partiers looking to push the government out of the monetary-policy-making business.

GOLD IS back, what with libertarians the country over looking to force the government out of the business of monetary-policy making. How? Well, by bringing back the gold standard of course.

GOLD IS back, what with libertarians the country over looking to force the government out of the business of monetary-policy making. How? Well, by bringing back the gold standard of course.

There’s no better place to see just how real this oddball proposal is than in Iowa, with its caucuses just a few months away. In June, prospective voters were entertained not just by the candidates but also by the spectacle of an eighteen-day, multicity bus tour cosponsored by the Iowa Tea Party and American Principles in Action, or APIA. (The bus was actually a giant RV with a banner on the side featuring images of the U.S. Constitution, the American flag and the web address www.teapartybustour.com.) APIA is the nonprofit 501(c)(4) arm of the American Principles Project, the parent group of Gold Standard 2012. Gold Standard 2012 “works to reach out to lawmakers to advance legislation that will put the U.S. back on the gold standard” (quoting its blog). The goal of the bus tour, according to Jeff Bell, policy director of APIA and former Reagan aide, was to interest potential caucus voters in the idea that the United States should return to the gold standard, in the expectation that vote-hungry candidates for the Republican nomination would respond to a public groundswell.

The candidates, for their part, were cautious. Businessman Herman Cain, having backed the gold standard in earlier speeches, acknowledged a change of heart on the grounds that “one of my economic advisers said that it’s going to be more difficult than practical.” Minnesota congresswoman Michele Bachmann averred only that she would “take a close look at the gold standard issue.” Such caution did not, however, prevent Cain and Bachmann, along with former Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty, former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum, former New Mexico governor Gary Johnson and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich from joining up with APIA’s magical mystery tour.

Nor did it prevent state legislators from attempting to move ahead on their own. A Montana measure voted down by a narrow margin of fifty-two to forty-eight in March would have required wholesalers to pay state tobacco taxes in gold. A proposal introduced in the Georgia legislature would have called for the state to accept only gold and silver for all payments, including taxes, and to use the metals when making payments on the state’s debt.

In May, Utah became the first state to actually adopt such a policy. Gold and silver coins minted by the U.S. government were made legal tender under a measure signed into law by Governor Gary Herbert. Given the difficulty of paying for a tank of gas with a $50 American eagle coin worth some $1,500 at current market prices, entrepreneurs then floated the idea of establishing private depositories that would hold the coin and issue debit cards loaded up with its current dollar value. It is unlikely this will appeal to the average motorist contemplating a trip to the gas station since the dollar value of the balance would fluctuate along with the current market price of gold. It would be the equivalent of holding one’s savings in the form of volatile gold-mining stocks.

Historically, societies attracted to using gold as legal tender have dealt with this problem by empowering their governments to fix its price in domestic-currency terms (in the U.S. case, in dollars). But the idea that government should legislate the price of a particular commodity, be it gold, milk or gasoline, sits uneasily with conservative Republicanism’s commitment to letting market forces work, much less with Tea Party–esque libertarianism. Surely a believer in the free market would argue that if there is an increase in the demand for gold, whatever the reason, then the price should be allowed to rise, giving the gold-mining industry an incentive to produce more, eventually bringing that price back down. Thus, the notion that the U.S. government should peg the price, as in gold standards past, is curious at the least. More curious still is the belief that putting the United States on a gold standard would somehow guarantee balanced budgets, low taxes, small government and a healthy economy. Most curious of all is the contention that under twenty-first-century circumstances going back to the gold standard is even possible.

FOR THIS libertarian infatuation with the gold standard, one is tempted to credit, or blame, the godfather of the Tea Party movement, Texas’s Ron Paul. (The Tea Party has its own spontaneous origins, to be sure, and Paul is reluctant to claim credit for its existence. But his success in using new media to raise $6 million for his 2007 presidential bid on the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party by appealing to hot-button issues like debt, taxes and government infringement on personal liberties provided the template for the movement’s subsequent growth.) Paul has been campaigning for returning to the gold standard longer than any of his rivals for the Republican nomination—in fact, since he first entered politics in the 1970s.

Paul is also a more eloquent advocate of the gold standard. His arguments are structured around the theories of Friedrich Hayek, the 1974 Nobel Laureate in economics identified with the Austrian School, and around those of Hayek’s teacher, Ludwig von Mises. In his 2009 book, End the Fed, Paul describes how he discovered the work of Hayek back in the 1960s by reading The Road to Serfdom. First published in 1944, the book enjoyed a recrudescence last year after it was touted by Glenn Beck, briefly skyrocketing to number one on Amazon.com’s and Barnes and Noble’s best-seller lists. But as Beck, that notorious stickler for facts, would presumably admit, Paul found it first.

The Road to Serfdom warned, in the words of the libertarian economist Richard Ebeling, of “the danger of tyranny that inevitably results from government control of economic decision-making through central planning.” Hayek argued that governments were progressively abandoning the economic freedom without which personal and political liberty could not exist. As he saw it, state intervention in the economy more generally, by restricting individual freedom of action, is necessarily coercive. Hayek therefore called for limiting government to its essential functions and relying wherever possible on market competition, not just because this was more efficient, but because doing so maximized individual choice and human agency.

The book was a powerful call to arms for the opponents of big government. But in fact it said relatively little about monetary policy. Writing in the early 1940s, Hayek was more concerned with the social and economic consequences of central planning in the Soviet Union, National Socialism in Germany, and the increasing scope of government economic intervention elsewhere, first during the economic crisis of the 1930s and then in World War II. Indeed, monetary policy as we know it played little role in regulating the market in either Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia; the same was true of other countries in the exceptional circumstances of wartime. By and large this remained the case in the 1950s.

When reliance on monetary fine-tuning then increased in the 1960s, Hayek shifted his focus. In his 1976 study, The Denationalization of Money, he emphasized the government’s monopoly on printing money as the thin edge of the wedge that restricted individual decision making and gave the state additional resources with which to expand its powers. Moreover, the government’s control over currency led to instability in the market economy: “its susceptibility to recurrent periods of depression and unemployment.” It is a cycle that, once started, has no end.

For according to Hayek, democratic governments are temperamentally incapable of resisting pressure from special interests (whether it be farmers, unions or big corporations) clamoring for assistance, and they turn to the central bank to help underwrite their responses. The central bank thus buys the government’s bonds with newly minted currency and this, Hayek reasoned, inevitably fuels inflation. That inflation creates an unsustainable boom that eventually collapses, in turn creating further pressure for the government to intervene to stabilize an evidently unstable economy. Inflation, through its tendency to redistribute income and wealth largely to the detriment of the least advantaged members of society, further undermines popular support for the market system. What’s more, people can find it difficult to tell whether everything costs more or just a subset of goods, causing them to make bad economic decisions. This reduces the efficiency of production, reinforcing the impression that the market is incapable of delivering the goods. That in turn intensifies the pressure for government to intervene further and for the central bank to respond with exceptional measures of support. The result is yet another round of inflation and instability.

Exiled from Austria as a result of the Anschluss, Hayek saw the slippery slope from managed money to state control of the economy, and from there to the suppression of political freedoms, as self-evident. And having firsthand experience with the Central European hyperinflations of the 1920s, Hayek certainly knew from monetary instability. On taking power the Nazis may have retained the facade of the gold standard, but among their first acts was to broaden the restrictions on imports and exports of gold originally imposed by the Weimar government during the 1931 financial crisis. This largely cut off international transactions, allowing Hitler to expand public spending, including on the military, unrestrained by fears that the mark would collapse as it had ten years earlier.

In fact this may have been one of the few actual examples of Keynesian demand stimulus prior to John Maynard Keynes. (The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, in which Keynes first fully articulated the case for public spending to stimulate demand during downturns, was only published in 1936.) It was a successful example at that, judging from the macroeconomic consequences. Understandably, this did nothing to allay Hayek’s concerns.

Paul describes himself as having been profoundly influenced by Hayek’s account of how managed money opened the door to the disaster that was Nazi Germany. And he sees the United States walking down the same treacherous path. In End the Fed, he devotes a long passage to Richard Nixon’s decision in August 1971 to close the gold window—to suspend the statutory obligation of the United States to pay out gold to foreign governments holding U.S. dollars at a fixed price of $35 an ounce—singling that choice out as the key event prompting him to run for Congress. The Bretton Woods system, of which the $35 gold peg was an artifact, may have been only a “pseudo-gold standard” (Paul’s words), in that the commitment to exchange gold for dollars was extended only to foreign governments and central banks. But its abandonment, as Paul describes it, cleared the way for the dreaded specter of fiat money. It removed all remaining restraints on the ability of the central bank to underwrite the government’s budget deficits. It gave the Federal Reserve System full freedom to manipulate the country’s money supply. It was an “unprecedented experiment” in monetary planning.

And, much as Hayek would have predicted, it was accompanied by other measures expanding government control of the economy. Nixon supplemented his decision to abandon the gold standard with wage and price controls. He slapped a 10 percent surcharge on U.S. imports, discouraging free international trade. He allowed the budget deficit to widen further, famously justifying the deficit spending used to goose the economy in the run-up to his 1972 reelection campaign on the grounds that “we are all Keynesians now.” The import surcharge and the wage and price controls were advertised as temporary, and history would prove them as such. But not so the budget deficits, aside from the brief period of balanced budgets in the mid-to-late 1990s. For Paul, those deficits were the inevitable consequence of managed money. They were steps down Hayek’s slippery slope. Hence his quest to end the government’s ability to manipulate the money supply: to “end the Fed” and restore the gold standard.

BUT IF Representative Paul has been agitating for a return to gold for the better part of four decades, why have his arguments now begun to resonate more widely? One might point to new media—to the proliferation of cable-television channels, satellite-radio stations and websites that allow out-of-the-mainstream arguments to more easily find their audiences. It is tempting to blame the black-helicopter brigades who see conspiracies everywhere, but most especially in government. There are the forces of globalization, which lead older, less-skilled workers to feel left behind economically, fanning their anger with everyone in power, but with the educated elites in particular (not least onetime professors with seats on the Federal Reserve Board).

There may be something to all this, but there is also the financial crisis, the most serious to hit the United States in more than eight decades. Its very occurrence seemingly validated the arguments of those like Paul who had long insisted that the economic superstructure was, as a result of government interference and fiat money, inherently unstable. Chicken Little becomes an oracle on those rare occasions when the sky actually does fall.

More than that, the period leading up to the crisis displayed a number of specific characteristics associated with the Austrian theory of the business cycle. The engine of instability, according to members of the Austrian School, is the procyclical behavior of the banking system. In boom times, exuberant bankers aggressively expand their balance sheets, more so when an accommodating central bank, unrestrained by the disciplines of the gold standard, funds their investments at low cost. Their excessive credit creation encourages reckless consumption and investment, fueling inflation and asset-price bubbles. It distorts the makeup of spending toward interest-rate-sensitive items like housing.

But the longer the asset-price inflation in question is allowed to run, the more likely it becomes that the stock of sound investment projects is depleted and that significant amounts of finance come to be allocated in unsound ways. At some point, inevitably, those unsound investments are revealed as such. Euphoria then gives way to panic. Leveraging gives way to deleveraging. The entire financial edifice comes crashing down.

This schema bears more than a passing resemblance to the events of the last decade. Our recent financial crisis had multiple causes, to be sure—all financial crises do. But a principal cause was surely the strongly procyclical behavior of credit and the rapid growth of bank lending. The credit boom that spanned the first eight years of the twenty-first century was unprecedented in modern U.S. history. It was fueled by a Federal Reserve System that lowered interest rates virtually to zero in response to the collapse of the tech bubble and 9/11 and then found it difficult to normalize them quickly. The boom was further encouraged by the belief that there existed a “Greenspan-Bernanke put”—that the Fed would cut interest rates again if the financial markets encountered difficulties, as it had done not just in 2001 but also in 1998 and even before that, in 1987. (The Chinese as well may have played a role in underwriting the credit boom, but that’s another story.) That many of the projects thereby financed, notably in residential and commercial real estate, were less than sound became painfully evident with the crash.

All this is just as the Austrian School would have predicted. In this sense, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman went too far when he concluded, some years ago, that Austrian theories of the business cycle have as much relevance to the present day “as the phlogiston theory of fire.”

But the Austrians then go on—and this is where they and other economists part company—to argue that the best and, ultimately, only feasible response to this destabilizing cycle is inaction. Inaction is counseled first because of the existence of moral hazard. If the culprits don’t feel pain and learn a lesson, they will engage in the same reckless behavior over and over again.

Second, the overhang of unsound investment projects must be liquidated in order to prevent them from becoming a drag on the economy, and discouraging that process only delays the subsequent recovery. Eighty years ago Lionel Robbins, then Hayek’s colleague at the London School of Economics, famously made these arguments about how governments and central banks should respond, or more precisely not respond, to the Great Depression of the 1930s. An American member of the Austrian School, Murray Rothbard, later applied the same argument to the Great Depression in the United States.

The first part of their logic is impeccable: inaction in the face of an unfolding financial crisis is a sure way of inflicting pain. Unfortunately, the pain is meted out to the innocent as well as the guilty. It is felt by the workers thrown out of jobs in the resulting recession as well as by financiers who see their portfolios shrink.

Society, in its wisdom, has concluded that inflicting intense pain upon innocent bystanders through a long period of high unemployment is not the best way of discouraging irrational exuberance in financial markets. Nor is precipitating a depression the most expeditious way of cleansing bank and corporate balance sheets. Better is to stabilize the level of economic activity and encourage the strong expansion of the economy. This enables banks and firms to grow out from under their bad debts. In this way, the mistaken investments of the past eventually become inconsequential. While there may indeed be a problem of moral hazard, it is best left for the future, when it can be addressed by imposing more rigorous regulatory restraints on the banking and financial systems.

And we have learned how to prevent a financial crisis from precipitating a depression through the use of monetary and fiscal stimuli. All the evidence, whether from the 1930s or recent years, suggests that when private demand temporarily evaporates, the government can replace it with public spending. When financial markets temporarily become illiquid, central-bank purchases of distressed assets can help to reliquefy them, allowing borrowing and lending to resume.

These statements are controversial. They are not what the critics of the Federal Reserve System see. They see a budget deficit that has grown explosively, which they take as evidence of government again pandering to special interests whose cries only grow louder in tough economic times. They see a Federal Reserve that has engaged in large-scale purchases of Treasury securities under the rubric of quantitative easing (QE), enabling this government spending. They see the central bank intervening in the mortgage and securitization markets in unprecedented ways. They see runaway inflation, if not in the data then in the offing.

Above all they see chronic high unemployment and a sluggish recovery in the face of all this governmental intrusion into the market. They see no evidence, in other words, that the interventions undertaken in response to the crisis have achieved their goals. To someone viewing the world through Austrian-colored spectacles, the evidence would again appear to line up.

In fact, the reason that monetary and fiscal stimuli did not bring unemployment down more quickly and unleash a more robust recovery is not that they were incapable of doing so but that they were undersized. Given what we know now about the severity of the shock, by the time the Obama administration intervened with a $787 billion fiscal stimulus, that stimulus should have been at least twice as large. This is the retrospective assessment of Christina Romer, Obama’s now-former Council of Economic Advisers chair, but her conclusion is widely shared. Similarly, to prevent nominal GDP from falling, which is the litmus test of an adequate monetary stimulus, the Fed should have engaged in some $2 trillion worth of Treasury-bond purchases—not the $600 billion stipulated under QE2. This point has been made most clearly by Joseph Gagnon, a former Fed official, but he is far from alone.

In the event, the decision on the size of the fiscal stimulus was taken not on economic but on political grounds. The president’s political advisers determined, given congressional hostility to increased government spending, that getting agreement to do more was impossible or at least too costly politically. The Fed similarly concluded, given the political firestorm unleashed by its earlier interventions, that it could not make an open-ended commitment to raising nominal GDP. All that would be tolerated by Congress was a QE2 that was limited in both size and duration.

Undersized monetary and fiscal stimuli were better than no monetary and fiscal stimuli. They prevented the financial system from collapsing, the economy from falling off a cliff and the Great Recession from turning into another Great Depression. But they had longer-term costs: they failed to deliver all that was promised by their architects, whose arguments therefore came under a cloud of suspicion. Given the association of increased government spending with continued high unemployment, the former was blamed for the latter. The expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet similarly came to be seen as a cause of, not a solution to, the problem of sluggish recovery.

The only lasting answers to economic stagnation, it follows in this view, are deep spending cuts and measures to prevent the further expansion of the Fed’s holdings. And the only guaranteed way of achieving that is by putting the country back on the gold standard.

BUT TO invoke the wisdom of Herman Cain, returning to the gold standard would be more difficult than practical. Envisioning a statute requiring the Federal Reserve to redeem its notes for fixed amounts of specie is easy, but deciding what that fixed amount should be is hard. Set the price too high and there will be large amounts of gold-backed currency chasing limited supplies of goods and services. The new gold standard will then become an engine of precisely the inflation that its proponents abhor. But set the price too low, and the result will be deflation, which is not exactly a healthy state for an economy.

Given the inflation-phobic nature of gold-standard proponents, deflation would seem to be the more likely scenario. In response, we are counseled not to worry. In End the Fed Paul describes how the United States returned to the gold standard in 1879 after a two-decades-long hiatus caused by the Civil War. Resumption, as this decision was known, pegged the price of gold at levels lower than during wartime, leading to an extended period of deflation. If we could do it then, the implication follows, we can do it now.

Then again, there are some things you don’t want to try at home. The distributional effects of deflation are no happier than those of inflation. In this case it is debtors with obligations fixed in nominal terms, rather than creditors with assets fixed in nominal terms, who are unable to protect themselves. The populist revolt of the 1880s was stoked by farmers with fixed mortgages who labored under growing debt burdens and financial distress as a result of falling crop prices. Nor is deflation likely to support robust economic growth, as any close observer of the Japanese economy will tell you. Because nominal interest rates are not easily reduced below zero, the faster the price level falls, the higher will be the real interest rate (the real cost of borrowing and investing). The robust investment and job creation prized by the gold standard’s champions and the deflation they foresee are not easily reconciled, in other words.

Proponents of the gold standard thus face a Goldilocks problem: the porridge must be neither too hot nor too cold but just right. What temperature exactly, pray tell, might that be? And even if we are lucky enough to get it right at the outset, consider what happens subsequently. As the economy grows, the price level will have to fall. The same amount of gold-backed currency has to support a growing volume of transactions, something it can do only if the prices are lower, unless the supply of new gold by the mining industry magically rises at the same rate as the output of other goods and services. If not, prices go down, and real interest rates become higher. Investment becomes more expensive, rendering job creation more difficult all over again.

Under a true gold standard, moreover, the Fed would have little ability to act as a lender of last resort to the banking and financial system. The kind of liquidity injections it made to prevent the financial system from collapsing in the autumn of 2008 would become impossible because it could provide additional credit only if it somehow came into possession of additional gold. Given the fragility of banks and financial markets, this would seem a recipe for disaster. Its proponents paint the gold standard as a guarantee of financial stability; in practice, it would be precisely the opposite.

The Austrian response is: eliminate the lender of last resort and crises won’t happen in the first place. The kind of reckless risk taking that led to the recent financial crisis won’t take place if there is no longer an expectation of bailouts. The strongly procyclical behavior of money and credit that has underwritten destructive boom-and-bust cycles in the past will be no more. As Paul has put it:

Rampant monetary growth has led to historic high asset inflation, massive speculation, over-capacity, malinvestment, excessive debt, negative savings rate, and a current account deficit of huge proportions. These conditions dictate a painful adjustment, something that would have never occurred under a gold standard.

About this last assertion, history suggests otherwise. Bank lending was strongly procyclical in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gold convertibility or not. There were repeated booms and busts, not infrequently culminating in financial crises. Indeed, such crises were especially prevalent in the United States, which was not only on the gold standard but didn’t yet have a central bank to organize bailouts.

The problem, then as now, was the intrinsic instability of fractional-reserve banking. Banks are financial intermediaries. They are in the business of lending out the money they borrow from their depositors. This means that they keep on hand as reserves only a fraction of their deposits. But this exposes them, by their very nature, to a problem of confidence. As in the famous scene in It’s a Wonderful Life, if depositors lose confidence in the security of their funds, for any reason, they will demand them back, but the bank will not have them in liquid form. Moreover, because banks operate in the information-impacted part of the economy—they are in the business of acquiring information about specialized borrowers whose prospects are difficult for arms-length capital markets to assess—information about their own financial condition is necessarily imperfect. This is why confidence problems are intrinsic to fractional-reserve banking and why an economy with a modern banking system needs a lender of last resort.

Credit Paul, once more, for anticipating the objection. The problem with the U.S. financial system, he argues, is not simply fiat money but fractional-reserve banking itself. And the solution, which should go hand in hand with restoring gold convertibility, is eliminating the latter. Banks should be required to limit their investments to liquid assets that can be sold off immediately in response to depositor demands. Banks would be forced to behave, in effect, like high-quality money-market mutual funds.

Not surprisingly, there were proposals along these lines, labeled “narrow banking,” in the wake of the recent financial crisis. But it is not hard to see why they failed to take off. Where, under such a system, would firms go for working capital? One answer is nowhere: they would be starved of funding. Another answer is that they could turn to a separate set of nonbank financial firms authorized to lend longer term than they borrow and otherwise permitted to take on risk. But this second solution, such as it is, would simply shift the locus of risk rather than eliminate it. It would not remove the need for a lender of last resort but only change the name of the financial institutions that needed to be bailed out.

Lehman Brothers, recall, was not a commercial bank. It didn’t take deposits. But when it did not receive lender-of-last-resort support, its failure threatened to bring down the entire U.S. financial system. In response to this scare, governments—not just in the United States, but in all Group of Twenty countries—announced that no more systemically significant financial institutions would be allowed to fail. This may have been too much of a blanket guarantee, but it was indicative. It is implausible, in other words, to imagine that the authorities could simply stand back when a systemically significant nonbank financial intermediary experiences serious problems.

Finally, it is far from self-evident that putting the United States on a gold standard would enhance fiscal discipline. Its champions argue that allowing the Fed to issue notes only in amounts commensurate with its gold holdings, by preventing it from purchasing Treasury paper, will subject the government to market discipline. No longer on drip feed from the central bank, the Treasury will be at the mercy of skeptical investors—the so-called bond-market vigilantes—who will force the government to put its fiscal house in order by selling bonds. The hard currency delivered by the gold standard will thereby guarantee that the government lives within its means.

Note that this is the same argument made by the champions of Argentina’s currency board in the decade leading up to that country’s sovereign default in 2001. It is the same argument made by the champions of Greece’s entry into the euro area prior to 2010. That the Central Bank of Argentina could create additional credit only when it acquired additional dollars (Argentina’s currency board being a dollar standard, with the peso pegged to the dollar at one to one, rather than a gold standard per se) did not in practice prevent the government from issuing more debt than it could ultimately service. Similarly, that Greece no longer had an independent monetary policy once it adopted the euro did not prevent its government from issuing more debt than it ultimately could pay off. The simple fact that Greece no longer possessed an independent central bank with full freedom to finance the government’s budget deficits was not enough to concentrate the minds of shortsighted politicians. And in both cases, the bond-market vigilantes supposedly responsible for disciplining those politicians remained complacent for an extended period before awaking with a start, at which point all hell broke loose.

The same was true of the gold standard. Sovereign defaults were far from infrequent under both the pre–World War I and interwar gold standards, as the Peterson Institute’s Carmen Reinhart and Harvard’s Ken Rogoff show in their best-selling book This Time Is Different. Evidently, hard money is less of a guarantor of fiscal rectitude than popularly supposed.

What is needed, it might be argued, is a good, old-fashioned sovereign default to focus the minds of the politicians and the bond-market vigilantes. That would seem to have been the subtext of the debt-ceiling debate. It would also be a very high price to pay.

IF THESE problems with restoring the gold standard are so profound, why then do they fail to register with the libertarian critics of big government? The answer, to the contrary, is that they do. At the end of The Denationalization of Money, Hayek concludes that the gold standard is no solution to the world’s monetary problems. There could be violent fluctuations in the price of gold were it to again become the principal means of payment and store of value, since the demand for it might change dramatically, whether owing to shifts in the state of confidence or general economic conditions. Alternatively, if the price of gold were fixed by law, as under gold standards past, its purchasing power (that is, the general price level) would fluctuate violently. And even if the quantity of money were fixed, the supply of credit by the banking system might still be strongly procyclical, subjecting the economy to destabilizing oscillations, as was not infrequently the case under the gold standard of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

For a solution to this instability, Hayek himself ultimately looked not to the gold standard but to the rise of private monies that might compete with the government’s own. Private issuers, he argued, would have an interest in keeping the purchasing power of their monies stable, for otherwise there would be no market for them. The central bank would then have no option but to do likewise, since private parties now had alternatives guaranteed to hold their value.

Abstract and idealistic, one might say. On the other hand, maybe the Tea Party should look for monetary salvation not to the gold standard but to private monies like Bitcoin.

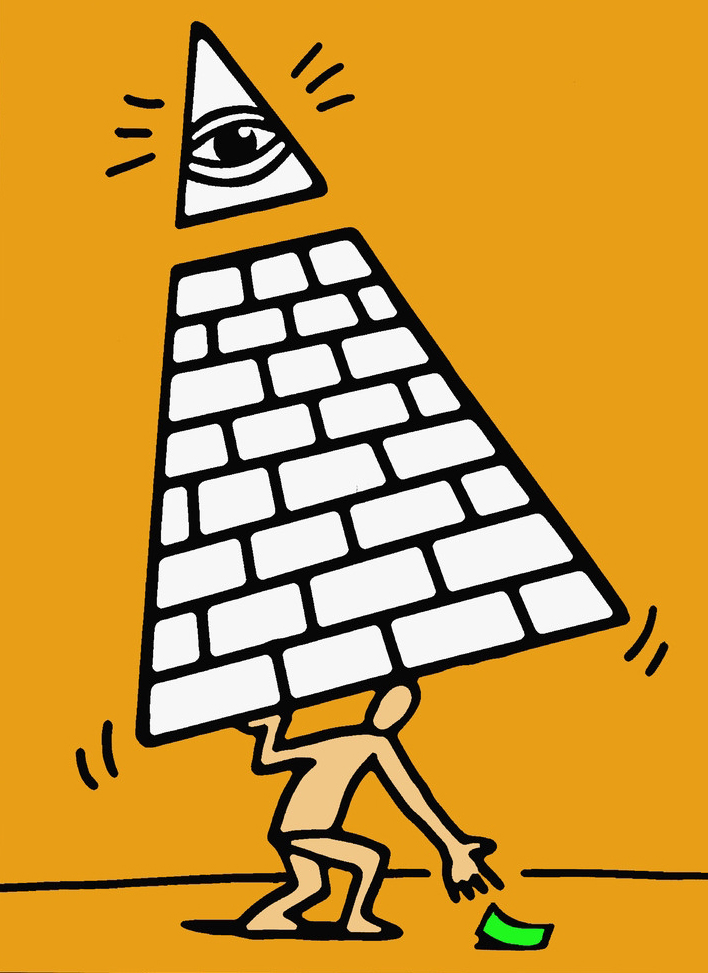

Image from Corbis

Image: Pullquote: Bizarre is the belief that putting the United States on a gold standard will somehow guarantee balanced budgets, low taxes, small government and a healthy economy.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: Bizarre is the belief that putting the United States on a gold standard will somehow guarantee balanced budgets, low taxes, small government and a healthy economy.Essay Types: Essay