Unfinished Mideast Revolts

Mini Teaser: The era of U.S.-approved, iron-fisted Arab dictators is over. Washington must get used to a Middle East in which public opinion matters to a much greater extent, anti-Western sentiment abounds and political Islam emerges as a major force.

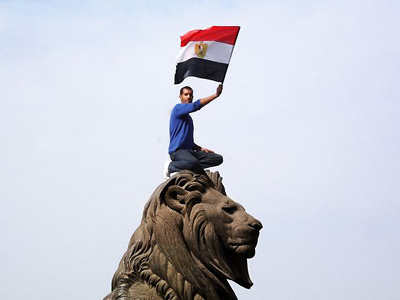

NOWHERE IN the world have the latest shocks to the Old Order been more powerful than in the Middle East and North Africa, where massive civic turmoil has swept away long-entrenched leaders in Egypt, Tunisia and Yemen, toppled a despot in Libya and now challenges the status quo in Syria. Over the past sixty years, the only other development of comparable game-changing magnitude was the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union.

NOWHERE IN the world have the latest shocks to the Old Order been more powerful than in the Middle East and North Africa, where massive civic turmoil has swept away long-entrenched leaders in Egypt, Tunisia and Yemen, toppled a despot in Libya and now challenges the status quo in Syria. Over the past sixty years, the only other development of comparable game-changing magnitude was the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union.

It isn’t clear where the region is headed, but it is clear that its Old Order is dying. That order emerged after World War II, when the Middle East’s colonial powers and their proxies were upended by ambitious new leaders stirred by the force and promise of Arab nationalism. Over time, though, their idealism gave way to corruption and dictatorial repression, and much of the region slipped into economic stagnation, unemployment, social frustration and seething anger.

For decades, that status quo held, largely through the iron-fisted resolve of a succession of state leaders throughout the region who monopolized their nations’ politics and suppressed dissent with brutal efficiency. During the long winter of U.S.-Soviet confrontation, some of them also positioned themselves domestically by playing the Cold War superpowers against each other.

The United States was only too happy to play the game, even accepting and supporting authoritarian regimes to ensure free-flowing oil, a Soviet Union held at bay and the suppression of radical Islamist forces viewed as a potential threat to regional stability. Although successive U.S. presidents spoke in lofty terms about the need for democratic change in the region, they opted for the short-term stability that such pro-American dictators provided. And they helped keep the strongmen in power with generous amounts of aid and weaponry.

Perhaps the beginning of the end of the Old Order can be traced to the 1990 invasion of the little oil sheikdom of Kuwait by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein—emboldened, some experts believe, by diplomatic mixed signals from the United States. It wasn’t surprising that President George H. W. Bush ultimately sent an expeditionary force to expel Saddam from the conquered land, but one residue of that brief war was an increased American military presence in the region, particularly in Saudi Arabia, home to some of Islam’s most hallowed religious shrines. That proved incendiary to many anti-Western Islamists, notably Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda terrorist forces. One result was the September 11, 2001, attacks against Americans on U.S. soil.

The ensuing decade of U.S. military action in Iraq and Afghanistan produced ripples of anti-American resentment in the region. The fall of Saddam Hussein after the 2003 U.S. invasion represented a historic development that many Iraqis never thought possible. But the subsequent occupation of Iraq and increasing American military involvement in Afghanistan deeply tarnished the U.S. image among Muslims, contributing to a growing passion for change in the region. Inevitably, that change entailed a wave of Islamist civic expression that had been suppressed for decades in places such as Egypt and Tunisia.

Meanwhile, the invasion of Iraq also served to upend the old balance of power in the region. It destroyed the longtime Iraqi counterweight to an ambitious Iran. This fostered a significant shift of power to the Islamic Republic and an expansion of its influence in Syria, Lebanon, the Gaza Strip and the newly Iran-friendly Iraqi government in Baghdad. Iran’s apparent desire to obtain a nuclear-weapons capacity—or at least to establish an option for doing so—tatters the status quo further. With Israel threatening to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities, many see prospects for a regional conflagration, and few doubt that such a conflict inevitably would draw the United States into its fourth Middle Eastern war since 1991.

In short, recent developments have left the Middle East forever changed, and yet there is no reason to believe the region has emerged from the state of flux that it entered last year, with the street demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt. More change is coming, and while nobody can predict precisely what form it will take, there is little doubt about its significance. Given the region’s oil reserves and strategic importance, change there inevitably will affect the rest of the world, certainly at the gas pump and possibly on a much larger scale if another war erupts.

A CAREFUL look at the history of the Middle East reveals that, although the West has sought to hold sway over the region since the fall of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, its hold on that part of the world has been tenuous at best. This has been particularly true since the beginning of the current era of Middle Eastern history, marked by the overthrow of colonial powers and their puppets.

Like so many major developments in the region, this one began in Egypt. On July 22, 1952, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser led a coup that toppled the British-installed King Farouk, a corrupt Western lackey. The son of a postal clerk, Nasser was a man of powerful emotions. He had grown up with feelings of shame at the presence of foreign overlords in his country, and he sought to fashion a wave of Arab nationalism that would buoy him up as a regional exemplar and leader. By 1956, he had consolidated power in Egypt and emerged as the strongest Arab ruler of his day—“the embodied symbol and acknowledged leader of the new surge of Arab nationalism,” as the influential columnist Joseph Alsop wrote at the time.

From President Eisenhower’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, Nasser secured a promise of arms sales, but Dulles failed to deliver. So Nasser turned to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who was happy to comply. The young Egyptian leader’s anti-Western fervor impressed Khrushchev, and he saw an opportunity: ship arms to Nasser and gain a foothold in the Middle East. The West’s relations with Nasser deteriorated further when Dulles withdrew financial support for the Egyptian leader’s Aswan Dam project. Nasser, in retaliation, seized the Suez Canal, the hundred-mile desert waterway that nearly sliced in half the trade route from the oil-rich Persian Gulf to Great Britain.

Britain joined with France and Israel in a military move to recapture the canal, but Eisenhower sternly forced them to halt their offensive and withdraw the troops. Thus did Nasser manage to secure the canal for his country for all time. Alsop and his brother Stewart, both Cold War hawks, complained that Britain’s options narrowed down to “the grumbling acceptance of another major setback for the weakening West.”

By engineering the anti-Farouk coup, then consolidating his power in Egypt and striking a powerful blow against the West at Suez, Nasser set in motion the events that forged the modern, postcolonial era in Middle Eastern history. In 1958, Iraqi officers toppled the pro-British King Faisal II, and cheering mobs dragged his body through the streets of Baghdad. The long and bloody Algerian revolution against French colonial rule finally forced France to give that country its independence in 1962. Morocco gained its autonomy from France two years later. In 1969, Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi overthrew the oil-rich King Idris and installed himself as the “Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution” in Libya.

In those days of Cold War confrontation, Moscow moved quickly to exploit the opportunity posed by this revolutionary wave and the anti-Western sentiment that undergirded it. Soviet diplomats in the region didn’t preach against Arab attacks on Israel in the long-running hostilities of the region. Regarding Middle Eastern oil, they said, in essence, “Take it; it was stolen from you.” The Soviets rubbed their hands in delight at the prospect of cutting off the West’s oil lifeline. They stood by their Middle Eastern clients in good times and bad by helping them rearm and providing political support after the Arab countries suffered humiliating defeats in the 1967 and 1973 wars with Israel.

But even before the 1973 hostilities, Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, made a decision that helped tip the scales of influence back toward the United States. He expelled thousands of Soviet military advisers that Nasser had invited into the country and curtailed his ties with Moscow. Then, in a dramatic move in 1977, he flew to Israel to announce his desire for peace before the Israeli Knesset. After two years of U.S.-mediated negotiations, the two countries signed a peace treaty that took Egypt out of the Arab conflict with Israel and altered the strategic landscape in the Middle East. It also bolstered the U.S. position in the region as America’s good offices became a significant element of influence.

Throughout the remainder of the Cold War and well into the post–Cold War period, events in the Middle East unleashed persistent threats to the stability of the postcolonial order set in motion by Nasser in the 1950s. That status quo survived in general form, but it was constantly beset by major upheavals and ominous rumblings just beneath the surface. This was reflected in the long, bloody Lebanese civil war of 1975–1990. It could be seen in the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which installed an Islamist regime in a nation that had been a steadfast U.S. ally and unleashed a bitter wave of anti-Americanism (culminating in the Tehran hostage crisis that lasted from late 1979 to early 1981). It was also reflected in the bloody Iran-Iraq War, which extended over most of the 1980s and consumed nearly 1.2 million lives on both sides. Another upheaval was the ten-year Algerian civil war of the 1990s, which claimed more than 160,000 lives.

These threats to stability also included, of course, the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian tensions, which defied persistent efforts at negotiation and erupted intermittently into violence of varying degrees of magnitude and intensity.

And yet, for all that, the fundamental contours of the region remained relatively intact as those strongman leaders, many allied with the United States to one extent or another, held firm to their autocratic regimes, their agencies of control and their citadels of corruption. Once again, Egypt set an example for the region. If Nasser’s brand of politics was fueled by an idealistic Arab nationalism and Sadat’s contribution was a search for accommodation with Israel (for which he won a Nobel Peace Prize), the next Egyptian leader, Hosni Mubarak, seemed fixated on the status quo and the politics of self-aggrandizement. He was the embodied symbol and acknowledged leader of Middle Eastern corruption, and his brand of politics was embraced by other leaders in the region.

For nearly sixty years, these leaders generally managed to enforce the Old Order. But now, with the Arab Spring and its aftermath, that Old Order is fading fast, and much of the region is being remade from the bottom up. What’s emerging is a strong sense that the Middle East needs to join the rest of the world and that popular sentiment should direct the destinies of the region’s nations and peoples.

AS THE countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe joined the West in developing modern global economies, the Arab world lagged far behind. And ordinary Middle Easterners were reminded of that fact every day as new Arab satellite-television networks such as Al Jazeera brought the modernizing world into their homes, over the heads of the state-controlled media.

Anyone who visited the non-oil-producing countries of the Middle East over the past thirty years could see how far behind the rest of the world they were in economic development. In Tangier, legions of unemployed young Moroccan men sat around with nothing to do but stare across the Strait of Gibraltar, hoping for a job on the European side. It was a tableau of despair that was repeated throughout the region.

One of the Arab world’s most glaring problems was its outdated educational system. According to the UN’s “Arab Human Development Report 2002,” few Arab schools could keep pace with the changes caused by globalization and technological advances. Clinging to old teaching methods that emphasized rote learning, Arab schools failed to teach critical thinking. Across the region, these schools produced legions of young Arab graduates who were unprepared for a modern, information-age global economy. In some countries, women were denied education altogether.

“With so little human capital available, relatively few entrepreneurs have invested in the Middle East, other than to harvest the region’s plentiful oil and gas resources,” wrote Kenneth Pollack, a Middle East specialist at the Brookings Institution, in a 2011 study of the Arab Spring. Those investments, he added, “have benefited the regimes and their cronies, but not the vast majority of the people.”

The result was massive unemployment, especially among the young. Many emigrated to Europe in search of work. But many others remained, living with their parents and unable to afford marriage.

Other problems included the lack of democratic rule and the endemic corruption that these regimes tolerated and sometimes encouraged. In most countries, so-called elections consisted of referendums in which voters could choose whether they approved or disapproved of the sitting leaders. Not surprisingly, the leaders often claimed 98 percent approval.

The leaders not only enriched themselves and their cronies but also developed pervasive internal-security forces and questionable legal systems to quash any dissent. In Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan and the Persian Gulf states, torture was a regular practice in government jails, according to the State Department’s annual human-rights reports.

With the pressure cooker of unemployment, official corruption and government repression building up for more than three decades, it was simply a matter of time and human nature before something snapped. It came on December 17, 2010, when a Tunisian vegetable peddler named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest the humiliating treatment he persistently received at the hands of a government inspector. His self-immolation would ignite the entire Arab world and eventually help bring down the Old Order.

BUT WHAT will the new order in the Middle East look like? It is still emerging. The discontent in Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq, Sudan and the Palestinian territories, which also share the demographic profile of high unemployment among young people with few economic prospects at home, has not yet reached a critical mass. Perhaps that is because the memories of civil conflict are still fresh in all of those countries. But unless the governments there take steps to address their economic problems, they easily could become targets of a new round of popular protests.

So far, the only rulers who have managed to hold back the popular pressures of the new Middle East are those who lead oil-rich monarchies. Saudi Arabia succeeded in buying off the malcontents in the kingdom by distributing more than $36 billion in additional benefits to a tiny population that already enjoys cradle-to-grave care. For a few months last year, protests by Bahrain’s Shia majority appeared to threaten the tiny island nation’s ruling al-Khalifa family, which is Sunni. The United States, which maintains a major naval base in Bahrain, pleaded with Bahrain’s rulers to make political reforms. But Saudi Arabia, already aghast at the failure of the United States to support Egypt’s Mubarak, a faithful U.S. ally for nearly thirty years, intervened on behalf of the regime. Without informing the Americans, Riyadh sent armored units across the causeway that links Bahrain to the Saudi mainland to help crush the Shia rebellion. For now, at least, Saudi Arabia and the other wealthy Gulf states have bought compliance with the status quo.

But Jordan and Morocco, the Arab monarchies that don’t have oil, are talking seriously about political changes in an effort to stay ahead of the revolution. In Morocco, King Mohammed VI is considering a new form of government that would transform his country into a constitutional monarchy.

As for the countries where the old autocrats fell, the Arab revolutions are still a work in progress. Public opinion will direct events to a much larger extent, in foreign policy as much as in domestic affairs. This can be seen in Egypt, which seems to be reclaiming its former role as the region’s center of gravity. If the recent contretemps over the detention of Americans working for several prodemocracy NGOs is any indication, Washington can expect more anti-American episodes in the future. Israel can also expect greater hostility. It is wildly unpopular in Egypt because of its treatment of the Palestinians. Few, however, expect the Israel-Egypt peace treaty to unravel. The Egyptian military still maintains enough power to keep both the peace treaty and U.S. ties intact.

But the West will have to get used to political Islam as a major force in the Middle East. In Tunisia, Islamists are behaving in accordance with the country’s moderate, pro-Western traditions. The Islamist Al Nahda party, long banned under Tunisia’s former rulers, won parliamentary elections last year but assembled a coalition with two liberal parties in an effort to form a government of national consensus. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, also banned under Mubarak’s rule, captured one-third of the seats in parliamentary elections, while the more conservative Salafist party won another 20 percent. Democracy in Egypt is pushing the country toward some form of Islamist structure, though its precise nature remains unclear. The test in Egypt is what kind of constitution the Islamists will write. Will it move the country from autocracy to the rule of law? Will the constitution guarantee individual rights for both men and women as well as protect minorities such as Egypt’s beleaguered Coptic Christian population? Will sharia law play a role? And how will the country’s ruling party behave the next time there is an election? Will it hand over power peacefully if it loses?

Only the future can answer these questions. After decades of political stagnation, the political ferment in the Middle East is only beginning, and any new order there could take years or even decades to develop. Adding to the region’s uncertain trajectory are the unresolved Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the growing threat of a war between Israel and Iran over Tehran’s nuclear-enrichment program.

Indeed, the only certainty in the new Middle East is the countless opportunities for statesmanship—and miscalculation—that will lie along the way.

Jonathan Broder is a senior editor at Congressional Quarterly. He spent seventeen years in the Middle East as a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press, NBC News and the Chicago Tribune.

Part of TNI's special issue on the Crisis of the Old Order.

Image: Kodak Agfa/Alvesgaspar

Image: Pullquote: Recent developments have left the Middle East forever changed, and yet there is no reason to believe the region has emerged from the state of flux that it entered last year.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: Recent developments have left the Middle East forever changed, and yet there is no reason to believe the region has emerged from the state of flux that it entered last year.Essay Types: Essay