When Camelot Went to Japan

Mini Teaser: RFK's public-diplomacy trip turned the relationship around.

THE UNITED States has security partnerships with numerous countries whose people detest America. The United States and Pakistan wrangled for seven months over a U.S. apology for the NATO air strikes that killed twenty-four Pakistani soldiers in 2011. The accompanying protests that roiled Islamabad, Karachi and other cities are a staple of the two countries’ fraught relationship. Similarly, American relations with Afghanistan repeatedly descended into turmoil last year as Afghans expressed outrage at Koran burnings by U.S. personnel through riots and killings. “Green on blue” attacks—Afghan killings of U.S. soldiers—plague the alliance. In many Islamic countries, polls reflect little warmth toward Americans.

THE UNITED States has security partnerships with numerous countries whose people detest America. The United States and Pakistan wrangled for seven months over a U.S. apology for the NATO air strikes that killed twenty-four Pakistani soldiers in 2011. The accompanying protests that roiled Islamabad, Karachi and other cities are a staple of the two countries’ fraught relationship. Similarly, American relations with Afghanistan repeatedly descended into turmoil last year as Afghans expressed outrage at Koran burnings by U.S. personnel through riots and killings. “Green on blue” attacks—Afghan killings of U.S. soldiers—plague the alliance. In many Islamic countries, polls reflect little warmth toward Americans.

Washington’s strategy of aligning with governments, rather than peoples, blew up in Egypt and could blow up in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Yemen. America’s alliances in the Middle East and Persian Gulf are fraught with distrust, dislike and frequent crisis. Is there any hope for them?

Turns out, there is. Fifty years ago, a different alliance was rocked by crisis and heading toward demise. Like many contemporary U.S. alliances, it had been created as a marriage of convenience between Washington and a narrow segment of elites, and it was viewed with distrust by the peoples of both countries. Yet a half century later, that pairing is one of the strongest security partnerships in the world—the alliance between the United States and Japan.

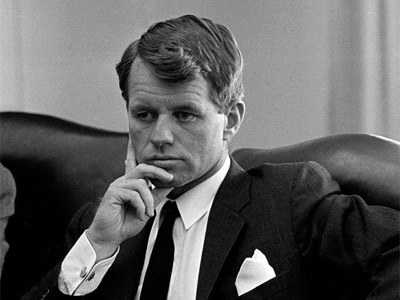

But in 1960, thousands of Japanese people poured into the streets of Tokyo to protest their country’s relationship with the United States. This shocked leaders on both sides of the Pacific, who realized that they had to take action or their partnership would die. Japanese officials crafted initiatives designed to build support for the alliance among the Japanese public. These included plans for the first U.S. presidential visit to Japan. In America, the incoming John F. Kennedy administration—fearing it could lose the linchpin of its strategy in the Pacific—supported the idea. It also made an unconventional (and in retrospect, deeply consequential) choice in its ambassador to Tokyo—Harvard professor Edwin O. Reischauer. In advance of his Japan trip, Kennedy sent his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to Tokyo. The president was assassinated before he could make the trip, but Robert Kennedy’s visit, and the networks and institutions it created, helped knit the U.S. and Japanese societies closer together. Two countries once dismissed as impossible allies forged, through careful and persistent diplomacy, a durable and warm relationship.

IN THE late 1950s, prior to Kennedy’s election, Japan’s people, flushed with national pride about their country’s extraordinary economic miracle, increasingly resented the U.S.-Japanese relationship. The two countries remained in the roles of conqueror and conquered. The U.S.-Japanese security treaty allowed the Americans to project force from Japan at will, and even empowered the U.S. military to subdue internal unrest. Furthermore, the Japanese, intensely protective of their nascent democracy, recoiled at Washington’s support for Japan’s anti-Communist stalwarts—Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leaders such as the hawkish prime minister Nobusuke Kishi, who had been a member of Japan’s wartime cabinet and was widely perceived as disturbingly nostalgic for the imperial era.

The Japanese also fumed over the continued U.S. administration of Okinawa, where America had seized land for military bases and a neocolonial paradise of compounds and manicured golf courses. As the Cold War intensified, the Japanese worried that those bases would draw them into a nuclear war with the Soviet Union or China. Then, in the thick of the 1960 debate over renewing the U.S.-Japanese security treaty, the Soviets shot down Francis Gary Powers’s U-2 spy plane, and Moscow and Beijing bellowed threats against countries allowing U.S. air bases on their territory. As scholar Kanichi Fukuda wrote at the time, suddenly “the new security pact [became] a matter of grave concern to the man in the street.”

Kishi was only able to pass treaty ratification by ramming it through the Japanese Diet after forcibly removing opposition politicians from the building. His citizens, already suspicious toward his leadership, roared at this betrayal of their young democracy. Demonstrators filled Tokyo’s streets and strained against the Diet’s gates. The following month, when a U.S. official arrived to plan a forthcoming visit by President Dwight Eisenhower, protestors surrounded his car and forced his evacuation by helicopter. Eisenhower’s visit—set to be the first by a U.S. president to Japan—was cancelled out of concerns for his safety. Americans suddenly realized that their alliance with Japan, called by one Japanese leader an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” floating off of the coast of the USSR, was foundering.

Dumbfounded American leaders gaped at the newspaper headlines and TV footage of their angry ally. What the hell was happening in Japan? Harvard’s Reischauer provided an answer in the pages of Foreign Affairs. “Never since the end of the war,” wrote the historian in the magazine’s October 1960 issue, “has the gap in understanding between Americans and Japanese been wider.” In his article, titled “The Broken Dialogue with Japan,” Reischauer lambasted the U.S. “occupation mentality” and urged the United States to change its attitudes and policies to avoid losing the alliance. He said most demonstrators “wanted the treaty killed and the present military link with the United States, together with the existing American bases in Japan, either eliminated at once or else ended in stages.” He cautioned that the issue of American control of Okinawa could someday break the alliance.

An interested reader of Reischauer’s diagnosis was John Kennedy, who upon becoming president tapped the scholar to be ambassador to Japan. Reischauer had no diplomatic experience, but he had been born in Japan, spoke the language and was a renowned expert on the country. Besides, he had an accomplished Japanese wife. Upon arriving in Japan, Edwin and Haru Reischauer immediately became a media sensation. The ambassador proclaimed his aim to allay the “serious misapprehensions, suspicions, and lingering popular prejudices” between the two peoples.

The Reischauers transformed what had been an isolated and imperious U.S. embassy. The ambassador recruited staff who understood the language and culture, promoting language training among embassy staff and families. The previous ambassador, Douglas MacArthur II, had not encouraged Japanese language study: “MacArthur was of the old school,” remembers Ernest Young, Reischauer’s special assistant. “There was French, and everything else meant going native. He thought that it was better not to know the local language.”

The Reischauers also fostered lectures and talks in coffee klatches and meals in which U.S. expatriates—businessmen and their families, military officers and wives, journalists and intellectuals—were educated about Japan. He wanted to show Japan as a nation “with a history and culture worthy of respect and study.” Reischauer cultivated relations with the U.S. military through repeated visits to Okinawa.

The “Reischauer line,” as it came to be known, advanced the idea of an “equal partnership.” The ambassador sought to convince the Japanese that Americans were not reckless militarists but rather prudent global players responding to dangerous threats; he sought to convince the Americans that Japan was an important ally deserving of respect and an equal voice. A true partnership, Reischauer believed, meant eliminating the vestiges of occupation, which meant returning Okinawa (and other seized Ryukyu Islands) to Japan. Reischauer criticized the U.S. high commissioner in Okinawa, Lieutenant General Paul Caraway, as running a “military dictatorship,” saying he was “doing everything to infuriate the local population and therefore exacerbate the situation without realizing the terrible mistakes he was making.” Okinawa was run, agreed Ernest Young, “like a colony.”

Caraway and others in United States Forces Japan viewed control over Okinawa as essential for U.S. power projection in the Pacific. But Reischauer argued that the best way to maintain a presence in Okinawa would be to return it to Japan. “Sooner or later,” he wrote, the Japanese “would get excited over Okinawa as an irredenta and this might ruin the whole Japanese-American relationship.” In recent Japanese elections, the Socialists had campaigned aggressively on this issue. As Young later explained, “If we were interested in keeping the LDP in power in Japan, we had to do something about Okinawa.”

But, as the security-treaty crisis showed, the future of the U.S.-Japanese alliance depended not only on the LDP but also on the support of the Japanese people. As George Packard (Reischauer’s assistant and later his biographer) wrote, the security-treaty crisis showed that “this support could not be taken for granted; it had to be earned.” Ties between the two peoples had to be established in order to convince the Japanese that this was a relationship not of domination but of partnership and respect.

As Reischauer sought to repair the frayed relationship, momentum grew for a U.S. presidential visit to Japan. Gunji Hosono, an elderly professor whom John F. Kennedy had befriended in 1951 while touring Japan, held meetings with the president, Reischauer and Robert Kennedy to discuss the possibility. Hosono had tracked down the captain of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which had sunk John Kennedy’s PT-109 boat in the Solomon Sea in 1943. Kennedy, who led his crew to rescue and saved an injured man, won a Purple Heart and the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his heroism. When Kennedy ran for the U.S. Senate in 1952, Hosono arranged for the Amagiri’s captain, Kohei Hanami, to write a letter to Kennedy (much publicized during the campaign), in which he conveyed his “profound respect to your daring and courageous action in this battle.” The Kennedys invited Hosono to attend Kennedy’s presidential inauguration as an honored guest, along with his daughter, Haruko. Hosono presented the president with a ceremonial scroll bearing the signatures of the Amagiri’s crew.

No sitting U.S. president had yet visited Japan, although Ulysses S. Grant had gone after leaving office. As noted, Eisenhower’s scheduled visit had been aborted in the chaos of the security-treaty crisis. Kennedy was smarting from some foreign-policy setbacks—most notably the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco—and wanted a diplomatic triumph. He envisioned a historic presidential visit to Japan during the 1964 reelection campaign. At its center would be a mesmerizing, human-interest reunion in Japan between the crews of PT-109 and the Amagiri, once enemies, now reconciled.

To test the waters, the president dispatched his most trusted adviser—Robert Kennedy. In Japan, Reischauer helped create an unofficial group to host the attorney general. Members of the “RK committee” included several relatively young, pro-American Japanese business and government leaders, among them the dynamic young LDP politician (and future prime minister) Yasuhiro Nakasone. Members of the RK committee worried that Japanese youth were being bewitched by Communism. Reischauer agreed that the “growing gap” between Americans and young Japanese people—the people who would be the future of the relationship—was a “truly frightening phenomenon.” They agreed that a visit from John Kennedy could help turn the tide—that Camelot could do some powerful bewitching of its own. First with Robert, then with Jack, the RK committee would show the Japanese a new, young and vigorous United States.

ON FEBRUARY 6, 1962, as Robert Kennedy’s motorcade drove through Tokyo’s streets toward a public appearance at Waseda University, reports were coming in from the CIA to expect trouble. Conferring across the jump seats of the car, the attorney general, Ambassador Reischauer and their aides discussed CIA warnings that Marxist student groups intended to disrupt the event. Memories flashed to 1960, when the thousands of protestors swarming Tokyo’s streets led President Eisenhower to cancel his visit. But despite their apprehension, as Reischauer later commented, “We decided at the last minute that it would look bad to back out.” The car slowed as it pulled in front of Okuma Auditorium, and a crowd of over five thousand students surged around it.

The students that greeted Robert and Ethel Kennedy turned out to be friendly. As Robert and Ethel pushed their way through the throng toward the auditorium, students laughed, cheered and stretched out their hands to touch them. But inside “the story was different,” as Kennedy recalled later.

Built to hold 1,500 people, Okuma Auditorium writhed with more than four thousand students. While many cheered the attorney general’s entrance, others jeered and booed. When Kennedy began to speak, Marxist students shouted and stomped their feet. One, Yuzo Tachiya, was particularly agitated. A leader in student government, he had distributed thirty thousand fliers that day to summon the crowd that now packed the auditorium. He had met with two professors who talked with him about how they were going to chair and translate the event. Tachiya watched, upset, as Kennedy substituted his own translator, “ignored the debate format set by his hosts,” and simply began speaking. The young man shouted from the audience that this was not right, that Kennedy should follow the format established by the professors who were hosting the event.

But when the Americans looked into the sea of black-uniformed students beneath the stage, what they saw, in the words of Kennedy’s assistant John Seigenthaler Sr., was “a skinny little Japanese boy” who was “tense, shouting, shouting, shouting, screaming at the top of his lungs.” If I ignore him, the attorney general thought, maybe he’ll be quiet. So he kept talking:

The great advantage of the system under which we live—you and I—is that we can exchange views and exchange ideas in a frank manner, with both of us benefiting. . . . under a democracy we have a right to say what we think and we have the right to disagree. So if we can proceed in an orderly fashion, with you asking questions and me answering them, I am confident I will gain and that perhaps also you will understand a little better the positions of my country and its people.

But Tachiya was still shouting, and “bedlam was spreading.” Kennedy recalled, “The Communists were yelling ‘Kennedy, go home.’ The anti-Communists were yelling back, and the others were yelling for everyone to keep quiet. I could see I wasn’t going to make any progress.” So Kennedy stopped talking. He acknowledged the heckler: “There is a gentleman down in the front,” he said, “who evidently disagrees with me. If he will ask a single question, I will try to give an answer. That is the democratic way and the way we should proceed. He is asking a question and he is entitled to courtesy.”

Kennedy extended his hand toward Tachiya, who grabbed it. The attorney general pulled him up onto the stage. “Bob treated him with great friendliness,” remembers Seigenthaler: putting his hand on his shoulder, telling him, “You go first.” He was “so cool,” marveled Ernest Young, “so cool.”

As the United States attorney general politely held the microphone for him, Tachiya blasted through the issues detailed on a leaflet his organization had prepared—the return of Okinawa; Article 9 of the Japanese constitution (which prohibits war making by the state) and the need for Japanese neutrality; the U.S. government’s treatment of the American Communist Party; the effect of a potential nuclear war on humanity; the CIA’s involvement in the Bay of Pigs; and America’s fledgling involvement in Vietnam. “His face,” the attorney general observed, “was taut and tense and filled with contempt.” Kennedy listened patiently, and finally Tachiya stopped talking. As Kennedy began to speak, the microphone went dead. Pandemonium broke out in the auditorium.

ROBERT KENNEDY, as Anthony Lewis of the New York Times once wrote, “rejected the politics of grins and blandness.” During the Japan visit planning, the attorney general had vetoed the normal round of receptions and photo ops. (“Nothing of any substance ever happens at a state dinner,” he said.) He wanted to meet ordinary Japanese in their daily lives. “You get him in touch with the people,” Seigenthaler told the RK committee. “He wants to meet the people.” During his visit, Kennedy debated Socialist political leaders, toured farms and factories, played football with Japanese children, walked through elementary schools, talked to university students, met with women’s groups, and watched sumo and judo demonstrations. He declined an offer to participate in the latter, sending in a replacement. (“I got thrown on my butt,” groused Seigenthaler.) One night in a bar in Ginza, Kennedy sampled sake and chatted with customers at the counter. He led some of the other Americans present in what he remembered as “a very off-key rendition” of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling.”

Ethel Kennedy, for her part, delighted the Japanese with a formidable mix of star power and approachability. “Call me Ethel!” she demurred when greeted with deep bows and formality. She talked about her daily life with her many children and their routines at their Virginia home, Hickory Hill. “Ethel loved people,” recalled Susie Wilson, a journalist and friend accompanying her on the trip. “She chatted with any and all of them, and they responded to her genuineness, and her concern for them and their cares.”

These efforts to get to know the people of Japan marked a new approach in alliance policy. The two societies had been kept separate, and U.S. diplomacy had focused on the military-strategic sphere at the expense of other spheres—particularly the cultural one. Disturbed at this trend, Reischauer had created at the U.S. embassy the position of cultural minister, bureaucratically equivalent to the political and economic ministers. “Money spent on diplomatic and cultural activities,” he lamented, “is proportionately far more productive than that spent on military programs but is always the first to be cut, even though the sums are inconsequential compared to military budgets.”

During Kennedy’s visit, the RK committee told him that the Soviet Union was skillfully waging a “cultural offensive” in Japan, while the United States was neglecting this realm. America’s cultural missions, the RK committee members told the attorney general, were inadequate, ill suited for Japanese audiences and ineffectual. “The importance of this issue,” Kennedy commented, “was brought home to me again and again throughout our trip.”

BACK ONSTAGE in Okuma Auditorium, confusion reigned. This is a fiasco, thought Reischauer, watching students heaving chairs at one another. Realizing something had to be done, he rose and held up his hands to the audience. To his surprise, the crowd looked up at him and quieted. In his fluent Japanese, he asked the students to remain calm. Meanwhile, someone located a bullhorn and handed it to Kennedy. The attorney general began earnestly:

We in America believe that we should have divergencies of views. We believe that everyone has the right to express himself. We believe that young people have the right to speak out and give their views and ideas. We believe that opposition is important. It’s only through a discussion of issues and questions that my country can determine in what direction it should go.

Kennedy remonstrated, “This is not true in many other countries . . . would it be possible for somebody in a Communist country to get up and oppose the government of that country?” He told the crowd, “I am visiting Japan to learn and find out from young people such as yourselves what your views are as far as Japan is concerned and as far as the future of the world is concerned.” After his remarks Kennedy took questions from the audience, and people responded positively. Susie Wilson commented, “He told them, ‘Come up here, and let me hear your concerns.’ It was the very essence of democracy.”

As the event was winding down, a student, the school cheerleader, shouted from the back of the auditorium his apologies for the treatment of the attorney general and his desire to make amends. Bounding onstage, he led the audience in a thundering rendition of the Waseda school song, “Miyako No Seihoku.” The group’s interpreter hastily scratched out a transliteration; Ethel, Reischauer, Seigenthaler and the rest of the entourage crowded around the attorney general and sang along exuberantly. Brandon Grove, a U.S. diplomat, recalled, “Each verse ended in shouts of ‘Waseda! Waseda! Waseda!’ and there’s where we excelled.”

The cheerleader, energetically gesticulating as he led the song, inadvertently punched Ethel Kennedy in the stomach, leading her to double over and stumble over a chair. Ethel immediately stood up and grinned as if nothing had happened. “She came from a huge family with plenty of touch football,” recalled Susie Wilson. “I don’t think it affected her at all.”

Fifty years later, reminiscing about the visit to Waseda, John Seigenthaler volunteered to sing its school song. He proudly sang multiple verses of scratchy, Nashville-accented Japanese. “That song,” he said, “turned the event into a stunning victory.” Anthony Lewis, covering the trip for the New York Times, recalled later that, although he’d been ill the night of the Waseda event, he’d had to learn the song because the group took to performing it at receptions and other events on the trip. (Lewis, too, offered up several bars of “Waseda!Waseda!Waseda!”)

Robert and Ethel would sing the song again at another Waseda event, when they returned to the university in 1964. Over the years, the family serenaded startled guests with the song at Hickory Hill. And in 1968, on the campaign trail in San Francisco, a giddy and exhausted trio of Kennedy, Ethel and Seigenthaler belted out “Miyako No Seihoku” while driving toward the airport, en route to the probable Democratic presidential nomination and an assassin’s bullet.

On their TV sets that evening, the Japanese watched what Reischauer called “one of the most dramatic live TV programs in history.” Though the auditorium’s microphones were dead, Kennedy could see that the TV microphones had remained on, so he knew he was speaking to the entire nation. The Japanese watched their young people heckling an invited, globally renowned dignitary and saw him respond with composure and respect. The scene was mortifying: legendary as attentive hosts, the Japanese had failed spectacularly. Kennedy later said he was surprised at the impact of the incident; Reischauer agreed, noting, “At the time, we did not realize what a tremendous victory we had just had.” The rest of the visit was a triumph.

Kennedy’s visit, coupled with the efforts of Reischauer and other committed leaders on both sides, heralded a new era in U.S.-Japanese relations. Reischauer had bonded with the attorney general, which gave him a direct line to the president—something that would prove invaluable in the ambassador’s struggles with the military. “When Caraway started attacking Reischauer,” Ernest Young noted, “the ambassador could resort to this backchannel through Bobby. He used it to save himself from political assassination from the Department of the Army.” In April 1962, President Kennedy announced for the first time that Okinawa would eventually be returned to Japan, implemented several reforms giving the Okinawan people greater autonomy and bolstered social programs on the neglected island. Although Kennedy’s assassination delayed the return, his policy ultimately was achieved ten years later.

After Robert Kennedy’s visit, the RK committee grew into a number of activities and institutions designed to foster an alliance between peoples rather than governments. It created a forum for bilateral dialogue called the Shimoda Conferences, named after that Japanese seaside town. At the initial meeting in 1967, more than seventy Japanese and American politicians, industrialists and academics discussed bilateral relations. Several American participants remarked that they had been shocked at the “passion” among their Japanese counterparts on the issue of Okinawa, which had received little attention in the United States.

Additionally, President Kennedy and Hayato Ikeda had at their 1961 summit initiated cabinet-level exchanges in the realms of the economy, scientific cooperation, and cultural and educational exchange. The delegation on the economy, chaired by Secretary of State Dean Rusk, met for the first time in Hakone, a town famous for its hot springs; the latter became formalized as the U.S.-Japan Conference on Culture and Educational Interchange (CULCON). CULCON aimed to broaden U.S.-Japanese relations beyond the political and military realms. Participants in its 1962 meeting (among them composer Aaron Copland) agreed on the need for language education and urged the creation of exchanges among artists, sculptors, writers and musicians. CULCON continues today.

Over the years, interlocutors became colleagues; colleagues became friends. The conferences were frequent, the beer cold, the conversations frank. U.S. and LDP alliance managers grew comfortable with one another—too comfortable. Forgetting that the LDP might not be in power forever, the Americans neglected to invite the Japanese opposition to the hot springs too. Former State Department official Richard Armitage lamented the American failure to “spread our network enough.” Observes George Packard, “The dirty little secret was that the United States got used to dealing with the LDP all of those years. The White House, the State Department—no one had developed any ties with any of the political opposition in Japan.” Packard adds, “This is something Reischauer would have abhorred.”

In 2009, Japanese voters upended fifty years of conservative rule, tossed the LDP out of office and installed the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). The DPJ had no experience governing and little expertise in foreign affairs. Its new prime minister, Yukio Hatoyama, had declared during his campaign that he wanted to create “a more equal alliance” with the United States and, ominously, “equidistance” between Washington and Beijing. Hatoyama withdrew Japanese participation in naval operations supporting the United States in the Indian Ocean, began cozying up to Beijing with talk of an “East Asian community,” and opened an investigation into shady agreements in the 1950s and 1960s between the LDP and Washington regarding the stationing of nuclear weapons.

The DPJ’s ascent discombobulated the U.S.-Japanese relationship. As U.S. alliance managers tried to figure out the post-LDP world, they had no one to call. All they had were their friends in Japan’s bureaucracy whom they’d cultivated over decades of delegations, dialogues and beer-soaked retreats. But their friends were on the outside too. Viewed by the distrustful DPJ as LDP minions, the bureaucrats had been benched by the Hatoyama government.

Unease turned to crisis when Hatoyama announced plans to scrap an agreement about restructuring U.S. bases on Okinawa. The deal, fourteen years in the making, was viewed by alliance managers as essential for maintaining the U.S.-Japanese security partnership. A key element of the agreement was the relocation of U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma because of the threat of accidents to the densely populated Ginowan city in which it sat. The plan was to relocate the base in Okinawa to Camp Schwab, near Nago City. But Hatoyama declared he wanted to move the Marines off Okinawa altogether.

Horrified alliance managers on both sides scrambled to repair the damage. As East Asia was rocked by crisis—shrill Chinese diplomacy in a 2010 standoff over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and North Korean attacks against South Korea—the DPJ was forced rapidly up its foreign-policy learning curve. The DPJ reined in the movement to distance Japan from the United States. It ushered Hatoyama out as if he were an uncle clutching a scotch and braying inappropriate remarks at a wedding. A new DPJ prime minister, Naoto Kan, smoothly took up the microphone: ladies and gentlemen, please excuse the disruption and return to your dessert. The Futenma deal was back on track.

Thus, the crisis in the alliance eased, and subsequent events only made the Japanese people more receptive to arguments about the need for a strong U.S.-Japanese alliance (and for the Futenma relocation to go forward). After the 2011 tsunami and nuclear disaster, the Japanese public witnessed an American outpouring of sympathy, aid and emergency assistance. And the following year, as Japan’s leaders and people watched Chinese mobs burn and loot Japanese businesses amid expressions of genocidal rhetoric, Japanese fears of China soared. Japanese politicians now compete to outdo one another as the toughest on China and the ablest manager of U.S.-Japanese relations.

But relocating Futenma still remains a thorny business. Hatoyama’s support for ejecting the U.S. Marines buoyed the hopes of the Okinawan antibase movement: ebullient Okinawans subsequently elected antibase mayors and a governor. Many Okinawans want the base gone—not relocated. In this new political setting, Tokyo will find it more and more difficult to relocate Futenma; it will likely require increasingly heavy-handed behavior by the center toward its resentful periphery.

Perhaps alliance managers can restructure U.S. forces in Okinawa in ways that the local population will accept. Perhaps the U.S. military can communicate better with the islanders and more effectively train U.S. soldiers so as to avoid the kind of incidents that have harmed Okinawans and aggravated relations in the past. In other words, perhaps (as Reischauer would encourage), Okinawans can be “brought in” to the alliance. Already, many locals have been brought in, because over the years marriages have connected U.S. servicemen and local families, and many livelihoods on Okinawa depend on the bases.

An alternative view, however, is that perhaps no amount of community relations (which, indeed, the U.S. military has already extensively pursued) can address the fundamental dilemma of Okinawa. A half century ago, Tokyo and Washington shook hands on a deal in which the United States would defend Japan, allowing it to enjoy a light defense burden and superpower protection, and Japan would provide bases for the U.S. military, giving a distant power a strategically located “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Okinawa’s bases dwell at the center of this deal. Perhaps there is no amount of finessing that can both preserve the alliance and satisfy Okinawans.

SIMILARLY, PERHAPS there is a limit to the United States’ ability to create warm relationships with some of its contemporary allies in the Middle East, where anti-American sentiment is strong. Nevertheless, the case of the U.S.-Japanese alliance offers lessons as Washington seeks to maintain and improve its crisis-prone relationships in the Middle East, where Washington retains some unfortunate diplomatic habits.

In his book Imperial Life in the Emerald City, Rajiv Chandrasekaran chronicles how personnel for the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Iraq were chosen not for their professional expertise or regional knowledge but instead for their loyalty to the George W. Bush administration. Once in Iraq they fortressed themselves away from the local population. In an eerie echo of the U.S. occupation of Japan, Chandrasekaran writes of the CPA diplomats: “Many of them spent their days cloistered in the Green Zone, a walled-off enclave in central Baghdad with towering palms, posh villas, well-stocked bars and resort-size swimming pools.”

The already-problematic U.S. tendency to build high walls around its diplomats will be exacerbated in the era after the Benghazi attacks in Libya. As tragically highlighted by the murder of U.S. ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and other officials in Libya, U.S. diplomats face threats that are real and dire. Even in the comparatively low-threat Japan of the 1960s, it is important to note, Edwin Reischauer encountered a knife-wielding Japanese man in the embassy and suffered a terrible stabbing; he survived.

But, as the U.S.-Japanese experience shows, relations will suffer if diplomats’ encounters with an ally’s people are confined to glimpses through the window of a speeding limousine. Reischauer, Robert Kennedy and their Japanese partners transformed U.S.-Japanese relations by reaching out to the public. The United States has a powerful story to tell about religious tolerance, respect for diversity and governance by law. It needs to tell that story—even if it is shouted offstage in its first attempts.

The U.S.-Japanese case also shows that greater dialogue with an ally’s public—assisted by area experts such as Reischauer—can help American policy makers hear and understand the issues that are important to allies and thus help them identify vital accommodations that can sustain these relationships. Reischauer’s knowledge of Japan and his deep contact with its people, as well as the subsequent Hakone conversations among U.S. and Japanese leaders about Okinawa, paved the way for the return of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty—and averted what could have been an alliance-killing crisis between the two countries. In postinvasion Iraq, Chandrasekaran comments, while Iraqis were thrilled to be liberated and were eager to create a new country, “The CPA, in my view, squandered that goodwill by failing to bring the necessary resources to bear to rebuild Iraq and by not listening to what the Iraqis wanted—or needed—in terms of a postwar government.”

Edwin Reischauer saw the rehabilitation of the U.S.-Japanese alliance as critically important in itself. But he also viewed it as a model for relations “across cultural and racial lines for the whole world.” He argued that the United States and Japan enjoyed “the closest relations that have ever been developed between a Western country and a major nation of non-Western cultural background.” It’s worth pondering how the lessons of the rescue of the U.S.-Japanese alliance might be usefully applied elsewhere, even if the prospects for a similar transformation may at first appear dim.

Jennifer Lind is an associate professor of government at Dartmouth College.

Image: Pullquote: After Robert Kennedy's visit, the RK committee grew into a number of activities and institutions designed to foster an alliance between peoples rather than between governments.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: After Robert Kennedy's visit, the RK committee grew into a number of activities and institutions designed to foster an alliance between peoples rather than between governments.Essay Types: Essay