How the Coronavirus Pandemic Is Changing the World—and the Future

Will nothing be untouched?

While most at present are dealing full-time with the day-to-day impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, it is always valuable to have an eye toward the future. Stratfor's forecast for the 2020s was published just as the novel coronavirus was spreading beyond China's borders. Clearly, the pandemic and the national and international responses will have reverberating effects into the decade that we did not foresee. But just as our 2000-2010 Decade Forecast was disrupted by the events of 9/11, we expect the underlying geopolitical trends will shape the response to the virus — and the way history moves forward after it passes.

COVID-19 in Context

At the moment, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be the sole focus of the international system, the black swan event that has overtaken all other priorities and dominates capital cities, financial centers, the news cycle and social media. But even a cursory glance shows the virus has not eliminated geopolitics. China and the United States continue to face off in the South China Sea. The United Kingdom and the European Union continue on the path to negotiate the terms of Brexit. War, insurgency and terrorism have not ceased. Global institutions have failed to overtake national initiatives.

If we look back just over a century ago, we can see another pandemic striking the world, crossing oceans, triggering localized quarantines and economic contractions. The 1918 influenza pandemic, aka the Spanish flu, broke out in the waning months of World War I and spread rapidly via the movement of forces in and out of the theater of battle. The impact of the pandemic compounded the human and economic toll of the global conflict, but did little to stem the broader trend toward the solidification of the nation-state as the centerpiece of the international system. Despite efforts to establish a League of Nations to oversee an interconnected world, the Europeans shaped a solution to the peace that laid the framework for the next war, and the Americans sought solace back in their sheltered continent.

The COVID-19 pandemic, at least by current estimates, will likely prove less deadly than the 1918 influenza, but it has already shown itself far more disruptive economically. The 1918 influenza only prolonged an economic crisis triggered by years of global war, and connections around the globe were more limited at the time. COVID-19, by contrast, emerged in a world of interconnectedness on a scale perhaps unimaginable a century earlier. It occurred amid U.S.-China trade tensions that were testing the limits of extreme globalization, once again raising questions about the future of power across the globe. It came as Europe was still coping with the social and political fallout of its debt crisis, Brexit and the rise of right-leaning political movements. And it came as global competition over technology, particularly information systems, was coming to a head and threatening global connectivity.

As we look at the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of Stratfor's Decade Forecast, we will be pondering many questions. While not an exhaustive list, the five broader trends below highlight areas the COVID-19 crisis intersects existing global strategic patterns. As with prior global and national crises, COVID-19 and the global response itself will not upend the system. But it will accelerate some patterns, disrupt others, and in the end reveal the deeper geopolitical stresses and strengths that shape the global system.

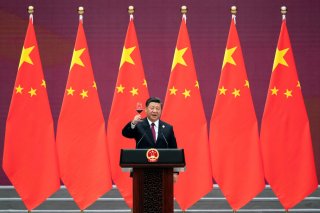

Does China 'Win' the COVID-19 War?

From the start, the question whether the COVID-19 crisis would strengthen or destabilize the Community Party's hold over China, and more specifically what impact it would have on the authority of Chinese President and Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, was commonly asked. The implication of the question was even larger — would this accelerate or decelerate China's "rise," and would it see China gain or lose power relative to the United States?

China's leadership was already strained by its attempt to reshape the Chinese economy; by protests in Hong Kong; resurgent anti-China sentiment in Taiwan; and by systemic economic, political and military pressure from the United States even before the viral outbreak. Moreover, the consolidation of power under Xi to facilitate economic restructuring and the turn to nationalism to hold the state together may have empowered the Chinese president, but it also concentrated responsibility for failures

China saw a massive slowdown or contraction in its economy in the first quarter, and is easing out of the most severe crisis as the rest of the world enters it — but the latter will reduce demand for Chinese products. China will face acute economic problems at least through the end of the year, if not beyond. We are watching for signs of trouble in China's shadow lending sector and for the depth of the hit on small- and medium-size enterprises, which employ more of the population but have more limited access to bank financing than the state-owned enterprises. Anecdotal evidence has emerged of social discontent with some of the response measures to the pandemic, including reports of challenges within the Party. But it is too early to tell if these are just the grumblings of the moment, symptoms of deeper discontent or reflect external entities trying to exploit a potential weak moment in China.

Another major question over the next several quarters will be the pace and scale of China's reinvigoration of the Belt and Road Initiative. If China sees the need to focus on internal consumption and economic activity, it may further trim such external projects. Even before COVID, Beijing was reassessing the value versus cost of many BRI projects. While China may capitalize on short-term gains in so-called soft power as it sends doctors and medical supplies to other countries, if it trims outbound infrastructure spending over the next few years, it will lose momentum in its bid to shape the political and security dynamics of its neighbors and partners.

How Will COVID-19 Impact Technology Competition and Information Infrastructure?

U.S. attempts to curtail the rollout of Huawei technology in global 5G infrastructure developments have strained relations between Washington and Beijing, but also between the United States and its own allies and partners. Now, the COVID-19 crisis and attendant quarantine measures have exposed the systemic weakness of communication infrastructure in many countries and communities, reinforcing the business-critical nature of such infrastructure. The crisis also has shown the vulnerability of information systems to misinformation and foreign manipulation.

It has also raised privacy concerns about increased government use of technology to track and manage the spread of COVID-19. Questions of government surveillance; personal information and privacy; government reach into economics and business; and the relation between local, federal and even pan-national governments and governance have been heightened in recent years, reflected in swings in politics, in debates over sovereignty, and in political and social disruption. Partially in reflection of the impacts of globalization, partly in reflection of natural societal and generational change, and partially in relation to shifts in demographics, these debates will be invigorated by COVID-19.

These competing concerns will intensify debates over personal information security from the state, and on national "cyber sovereignty." We expect increased attention on the funding and management of telecommunications and information technology infrastructure, with calls for more national funding — and control — over networks. Rather than reinforce the sense of "oneness" across the globe, the virus may instead accelerate moves toward greater fragmentation.

What is the Future of Multinational Organizations?

The bulk of the response to the COVID-19 crisis has been national in nature, not led by multinational institutions. Many global international institutions emerged at the end of World War II or the Cold War, very different times than the present. These institutions have not kept pace with a changing world, and the United Nations, the IMF, the WTO and other international institutions faced challenges of purpose and power even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The United States has long seen many of these institutions as either restricting or ineffective, while China has begun seeking to alter their direction to better fit its world vision.

If these institutions are seen to have failed in the current crisis after having done little in the global financial crisis a decade ago, being unable to stem conflict in the Middle East and South Asia, or to manage conflict migration or global climate change concerns, COVID-19 may invigorate debate over an overhaul of global governance. If not, it may simply cause nations to bypass many of these systems in pursuit of their own interests.

Will Supply Chain Disruptions Linger?

The COVID-19 pandemic is just the latest shock to globalized supply chains drawing attention to the risks to business and commerce continuity, and at times to national security. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, global supply chains were facing challenges from the U.S.-China trade war, and from rising economic nationalism across the globe. While the world hasn't broken free from the gravitational pull of China's manufacturing and consumer market heft, trade tensions plus rising labor costs in China had caused some manufacturing to begin moving to Vietnam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, preparation for Brexit and reassessments of supply chains as the United States revised NAFTA and trade arrangements elsewhere were also weighing on decisions surrounding supply chains.

Alone, the virus would be seen as a short-term disruption to global economic activity. Some companies managed to rapidly shift supplies outside of China in the early days of China's quarantines, while others retooled factories or relied on surplus stock. But over the past several years, moves away from just-in-time delivery and political or other shocks including China's unofficial boycott of South Korea over the THAAD deployment and the Fukushima disaster have increasingly forced companies to ensure flexibility in their supply chains, or to try to nearshore or onshore to better insulate from future global shocks.

What Broader Global Economic Disruptions Will Occur?

Commodity-dependent countries across the globe face longer term impacts from several months of consumption disruptions, and in some cases these problems are likely to linger far beyond the immediate term. In the Middle East and North Africa, where the expansion of U.S. energy production and the drive for renewables were already impacting supply and demand patterns, the additional drop in consumption related to COVID-19 will majorly impact national financial stability. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and others were facing headwinds in economic and reform efforts before COVID-19, and will still need to address rising youth populations with high expectations of government services, all amid falling revenues.

If reform efforts stall out, government reserves will shift to prioritize social spending over economic diversification, or over infrastructure development and outbound investment. Partially completed reforms may also prove socially destabilizing even as social spending picks up. While some countries could expect to turn to China at a time like this despite the cost to national sovereignty or at least political maneuverability, as noted above, China may well need to prioritize its own inward spending. Iranian behavior after a severe initial hit from COVID-19 will also play into regional competition and relations: Political upheaval in Iran may be just as destabilizing regionally as would a consolidation of Iranian government control.

A final place to watch over the coming decade for lingering impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic are countries heavily dependent upon external support, those squeezed between larger powers, or those on the global fringes. Pacific island nations, caught up in rising competition between China on one hand and the United States and Australia on the other, are facing major economic constraints in dealing with COVID-19, from the collapse of tourism to reductions in cargo and supplies. Places like Belarus, which have sought to balance Russian, European and growing Chinese interest, or Mongolia, which saw a significant drop in coal exports to China in the first quarter of the year, may find themselves with fewer options to retain independence of action.

Thinking Beyond COVID-19 is republished with the permission of Stratfor Worldview, a geopolitical intelligence and advisory firm.

Image: Reuters.