How Hedgehogs Are Benefitting From Coronavirus

Lower traffic volume means less animal lives taken.

Roads are an unforgiving place for wildlife. The almost constant rush of cars, lorries, vans and buses means that animals brave enough to attempt a crossing risk a swift death.

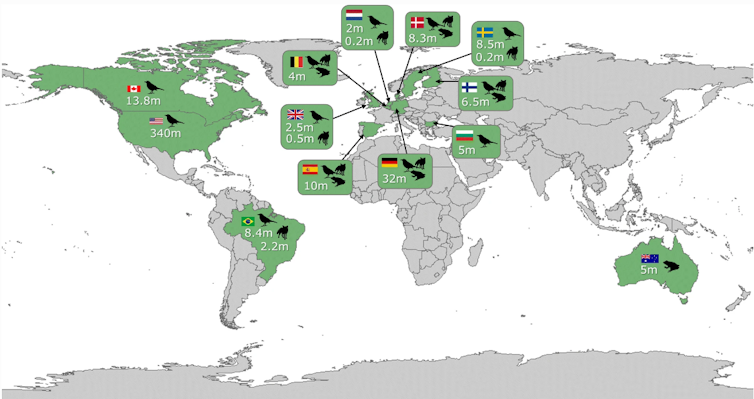

Collisions with vehicles kill millions of animals worldwide each year. In fact, it’s the largest human-driven cause of death for vertebrate land animals, even surpassing hunting.

The hums, beeps and vibrations from vehicles extend for kilometres from the road itself. Artificial light that shrouds roads at night is so bright that it is visible from space. These unnatural conditions can disorientate animals, disrupting how effectively they can communicate and forage.

Air and chemical pollutants, including dust, heavy metals and salt, affect the quality of land and water habitats that border roads. The UK alone has over 420,000 kilometres of road, which is equivalent to the distance between the Earth and the Moon. They dissect landscapes and confine wild populations to smaller and more fragmented patches of habitat. Although roads only cover 0.9% of the UK, their ecological impacts affect approximately 20% of the land cover.

But the pace of human life has slowed dramatically during the coronavirus pandemic, and less than a week into the nationwide lockdown, traffic volume fell by 73%. Perhaps one of the biggest beneficiary of this slowdown is the hedgehog – the hapless roamer of Britain’s roads.

Hedgehogs and roads

Because of their slow pace and tendency to freeze at the sight and sound of danger, hedgehogs are a familiar roadside casualty. Studies throughout Europe show that hedgehogs often make up over 50% of all mammal roadkill records and that an estimated 100,000 hedgehogs are killed on UK roads every year.

Hedgehog movements are also restricted by roads, as they tend to avoid the noise and commotion of traffic. This means populations become fragmented and cut off from one another.

Traffic has plummeted and ambient noise in cities is down between 20 and 50% compared to pre-lockdown levels. Urban species move to the rhythms of human activity. But at the moment, our empty and near silent streets are breaking down the barriers and perceived risks for hedgehogs on their nightly excursions of up to two kilometres. Road verges are going uncut as all non-essential work is postponed. That might provide more feeding opportunities and linear corridors to help hedgehogs roam freely and prosper.

While scientists can’t get outside to conduct road ecology research, citizen science provides a glimpse of what quieter roads might mean for wildlife. Project Splatter is a citizen science platform where you can report roadkill sightings of any animal in the UK.

There were 349 roadkill records across all species reported during the first week of April 2019. For the same week in 2020 – as the lockdown was entering its second week and hedgehogs were stretching their legs after winter hibernation – only 109 roadkill incidents were recorded across the UK. True, people are leaving their homes less so you might expect fewer sightings, but at the same time, more people are choosing to walk and cycle. That means more opportunities to spot squashed hedgehogs.

Life after lockdown

A poll by the AA reported that a fifth of respondents would drive less after lockdown. Some people will continue to work from home while many cities, including Paris and Milan, have announced “transport recovery” programmes, replacing roads with cycling and pedestrian lanes.

If the citizen science records during lockdown show a genuine fall in roadkill, it may temporarily stop the clock on declines of local hedgehog populations. But unless our travel patterns change for good – with fewer cars and more opportunities for animals to traverse roads safely, using wildlife crossings, for example – any benefits for hedgehogs will be short-lived.

As travel and other restrictions ease, people may avoid public transport to limit their exposure to the virus and take the car instead, perhaps more than they did before. Roads could roar back to life and hedgehogs would face riskier crossings again, finding they were lulled into a false sense of security. If the resurgence of traffic coincides with increased hedgehog movements during breeding season – between May and June – populations may face even greater danger.

Hopefully, our attitudes and commitment to coexisting with wildlife will last longer than the lockdown. The changes many people have noticed in local wildlife over recent weeks has shown that the human footprint on nature is not inevitable. We must redesign our urban areas and transport networks with nature in mind.

![]()

Lauren Moore, PhD Candidate in Road Ecology, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters