How the Navy Could Make Every Warship Into an 'Aircraft Carrier'

In short, sprearing out capability imparts staying power. A fleet in which everything that floats fights can absorb punishment and persevere on to victory. Which is the point of naval operations. Demonstrating the ability to operate in distributed fashion would convey to prospective foes like China that the U.S. sea services and fraternal armed forces are a tough if not impossible nut to crack.

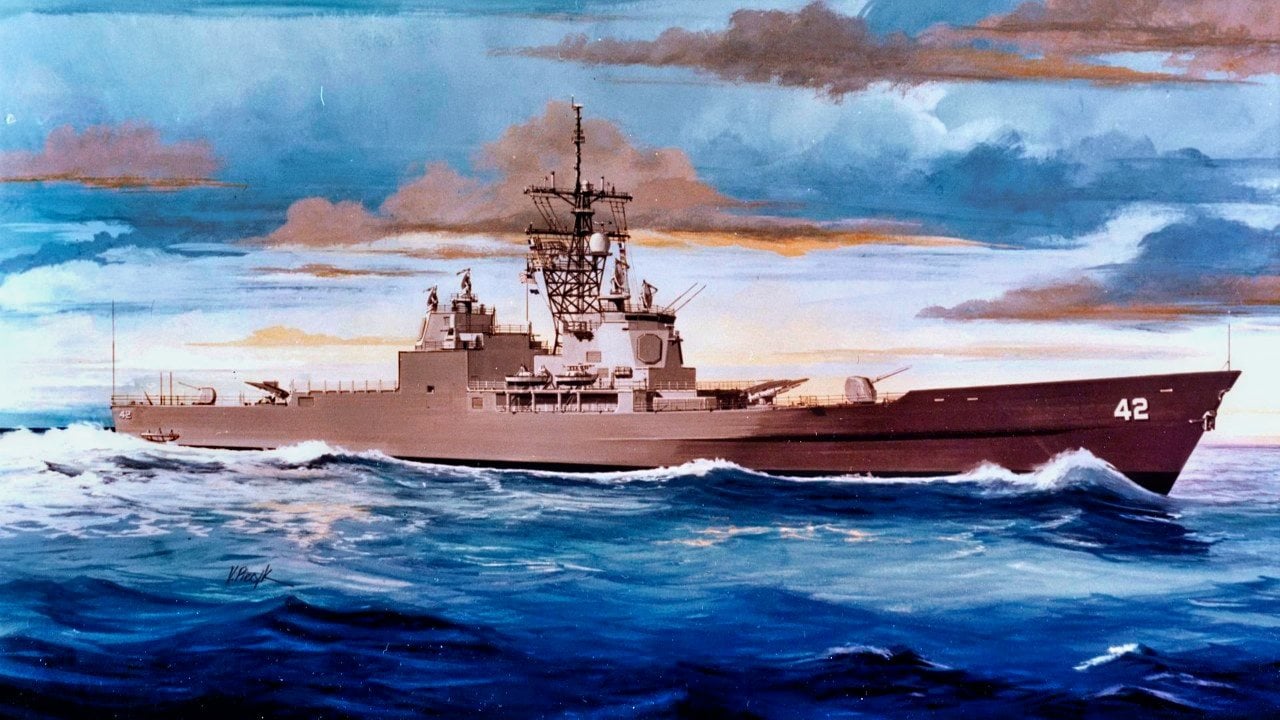

Last month over at the Naval Institute Proceedings, Lieutenant Commander Jeff Zeberlein proffers an intriguing, if oblique, take on the future of the aircraft carrier. Namely that in the age of uncrewed vehicles and artificial intelligence, every ship of war could—and should—be a “carrier” of some type or another. Miniaturization plus AI, he writes, makes proliferating aviation capability throughout the surface fleet—and not just to ships-of-the-line like cruisers and destroyers but to auxiliaries and amphibious transports—both feasible and prudent. Not every ship can be a big-deck carrier. Suitably repurposed, though, all could pitch in, enhancing the fleet’s effectiveness and durability in battle. In turn the fleet would be less reliant on the carrier air wing.

Thesis endorsed. Read the whole thing and hurry back.

For the most part Commander Zeberlein sagely refrains from opining on the shopworn—yet for navy people radioactive—topic of whether modern weapons technology, chiefly shore-based anti-ship weaponry, has rendered flattops (not to mention other major surface combatants) indefensible in combat. If it has, the U.S. Navy has saddled itself with a hyper-expensive fleet of wasting assets. That notion is heresy among naval-aviation proponents—including high-ranking naval officials and uniformed officers, as well as opinionmakers in academe and the think-tank world.

Why jab the hornet’s nest?

That being said, Zeberlein does imply that taxpayer dollars could be invested more wisely. For instance, he estimates that the U.S. Navy could pay to outfit the entire surface fleet with unmanned aircraft by foregoing one Ford-class nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, or CVN. That would amount to $13 billion in savings that could be reinvested elsewhere.

Such a tradeoff between traditional and nontraditional naval aviation would reduce the number of CVNs in the inventory from eleven to ten. That would equate to a nine-percent reduction or thereabouts in the big-deck carrier force for the sake of propagating aviation platforms throughout the fleet. So it seems that making every ship a carrier is not just technologically feasible but affordable at modest opportunity cost.

But finding the cash for the initiative still doesn’t settle things. In the annals of military history many unwise courses of action have been technologically feasible and affordable. The question is: does it make sense in practical terms to transmute every ship into an air-capable platform?

Why, yes; yes, it does.

For the sake of discussion, let’s follow Zeberlein’s lead and set aside budgetary infighting over building CVNs versus tricking out lesser aviation ships. In all likelihood the fleet needs both types of platforms. It is doubtful in the extreme that uncrewed aircraft will ever substitute in full for crewed warbirds like F/A-18 or F-35 fighter/attack jets or E-2D early-warning planes. So even if navy potentates embrace Zeberlein’s vision with zest, big-deck aircraft carriers and their aircraft complements will remain a core part of U.S. Navy fleet design.

Nor, it bears noting, do the national leadership and society necessarily have to choose between one and the other. If Congress were to pony up additional shipbuilding dollars, the navy could retain an eleven-hull CVN contingent while still equipping its surface fleet to host unmanned aerial systems.

Doing it all would be ideal.

What’s clear is that unmanned systems offer a promising adjunct to traditional naval air power. Captain Wayne Hughes, the dean of fleet tactics, designates scouting, command-and-control, and weapons range as the determinants of tactical efficacy at sea. Unmanned planes come in handy for monitoring the fleet’s surroundings—including, in times of battle, detecting, tracking, and targeting hostile forces. That’s the scouting function. They could contribute to command-and-control, for instance by relaying information and orders. They could even deliver ordnance against enemy vessels or shore targets, as Ukraine’s Black Sea campaign has demonstrated in abundance. In that case weapons range and precision would benefit.

Uncrewed vehicles have a major part to play in all dimensions of sea combat.

Moreover, such an approach would conform to current doctrinal wisdom. Stocking the fleet with unmanned aircraft would comport with “distributed maritime operations,” a concept much in vogue in the service, as well as companion sea-service operational concepts such as the U.S. Marines’ “expeditionary advanced base operations.” Scattering aviation capability and capacity throughout the surface force, and syncing up the fleet’s efforts with U.S. Marine and Army forces operating from Pacific islands—including uncrewed aircraft flying from dry earth—would reduce the likelihood that a foe such as China’s People’s Liberation Army could land a knockout blow against a U.S. task force by aiming everything at a high-value unit like an aircraft carrier.

Disperse capability across many fighting ships, and you reduce the percentage of combat power a successful enemy strike on a U.S. warship deducts from the fleet’s—and the joint force’s—overall strength.

In short, sprearing out capability imparts staying power. A fleet in which everything that floats fights can absorb punishment and persevere on to victory. Which is the point of naval operations. Demonstrating the ability to operate in distributed fashion would convey to prospective foes like China that the U.S. sea services and fraternal armed forces are a tough if not impossible nut to crack. That could give party overseers in Beijing pause. And giving hostile leaders pause when strife looms constitutes the essence of deterrence.

Zeberlein’s brief for distributed air operations deserves a fair hearing. Let’s hope it gets one at the Pentagon and in the halls of Congress.

About the Author: Dr James Holmes from the U.S. Naval War College

Dr. James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College and a Nonresident Fellow at the University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs. The views voiced here are his alone.